J.G. I’ve been thinking back to when I visited your studio in 2012. I spent ten days doing...well, you allowed me to do whatever I wanted really – the whole atmosphere in your studio was collaborative and generous. I focused on the Norton Lectures, which were mapped out in the notebooks. These had an impact on me – they were formative for me in many ways. But at the time, those performance lectures were still quite ephemeral, aside from, I suppose, a selection of videos in the form of the Drawing Lessons.

That aspect of your practice – the performance lecture aspect – when I came upon the notebooks it was this aha because the notebook felt like a raw home for that kind of work. The work in which the studio is a character and where you are a character – that’s now very well articulated and represented. At that time in 2012, these appeared to be like scores that opened up into this world. And although there were obviously many aspects of that kind of work and thinking appearing more widely in your practice, the notebook was all of it happening together: thinking, making, performing.

W.K. And you feel differently now? Or the practice feels different to you?

J.G. The question of sense-making is now inherent in everything. For example, What is the studio? Or the question, What does the artist do? What are these actions? Whereas, at that time...

W.K. You felt like it was a side question – more of an aside. Yes, that’s the trouble. I mean, you start with a new question, and it sticks with you, and then it’s no longer new. This is that fantastic moment when you didn’t know what you were doing. And it now seems that whatever I do, it is going to be a repetition of something that’s happened in the past, whether the idea of a lecture performance or the Drawing Lessons.

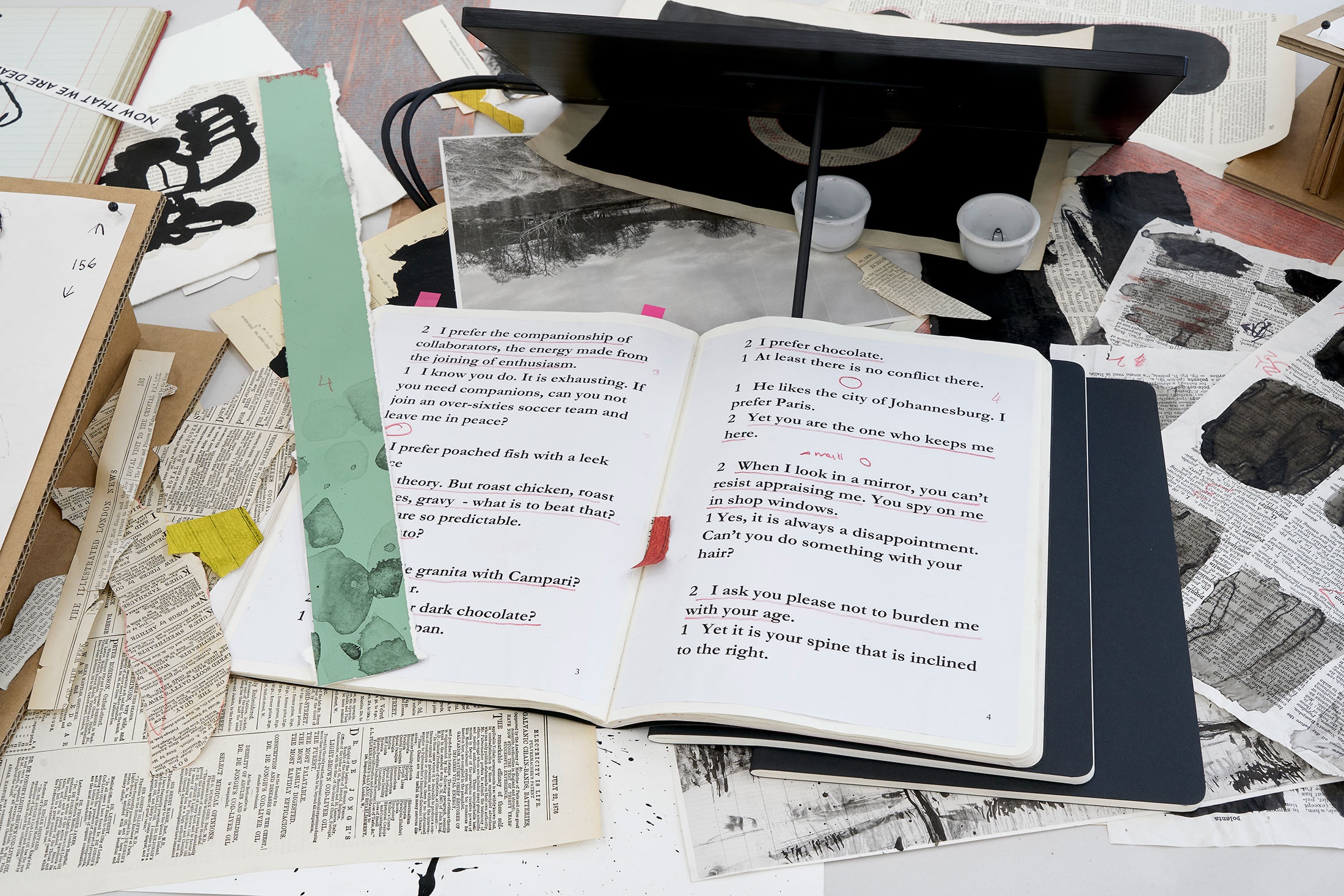

Within this exhibition, even the notebooks themselves are becoming a kind of work, which they’ve never been until now. The notebooks themselves have had several functions. The one is a kind of a repetition of symptoms. A lot of the notes in them – and I’m going through them now, and we’re looking through them as we prepare for the exhibition – are lists. What has since turned into the nine-part episodic series, Self Portrait as a Coffee Pot, got its start as a list of 15 possible episodes, and then, three pages later in the book, 12 possible episodes. The list is repeated again, almost identically, with one change, and this gives the sense of a list with its history. In other words, the notebook holds how thinking changes, not through extensive writing, but through, for example, simply listing headlines: The defence of optimism, provisionality of coherence, vanishing point. I used to do this on sheets of paper, but then I could never find them. They were all lost. The notebook became sensible, what notebooks are for – to keep things in an order, whether that’s the question of what you think, or the fragment that is key to an idea or statement, or the ‘headline’ that leads in one way or another onto the next note in a list.

Simple lists of tasks like anybody makes – go to the shop, buy fish, things like that – are not what I’m talking about when I talk about the studio lists. In the studio notebook, this would be an example of a ‘to do’ list: to do notes on warfare, to read the second book of Orfeo, to do the coffee-lift etching, to work on the coloured sheets, to glue the drawing sections together, to make another coloured sculpture.

Those are tasks to be done over the weekend or over the week. There’s a list of the different editing projects to happen in the next month: Fugitive Words, another short film, The Orfeo opera, a short film I need to make for Paris, making Pepper’s Ghost for Dresden, the facade of a building that might need a thing.

Task lists function as a kind of aide memoire.

And then there are notes from books that I’ve read – either phrases or notes to remember.

For example, one book has the libretto and some notes on the libretto. And then, fragments from Rilke, transcriptions of bits of his poems, notes from academic articles – a working book for a project that is live is used concurrently with another book that’s more like a journal-slash-repository of immediate ideas that arrive, of what gets put down in the notebook first.

J.G. Do you go back to the notebooks to revisit and reference things quite often?

W.K. I do, periodically. The ones I tend to reference the most are the ones that are lists of phrases called Words. There are several different Words notebooks.

They used to be bland...now when I’m hunting for something, I can know which notebook to find. On this one, I have a sticker saying glyphs. So I know where to look if I’m hunting for where did I do the quick sketches for the small sculptures? That helps me.

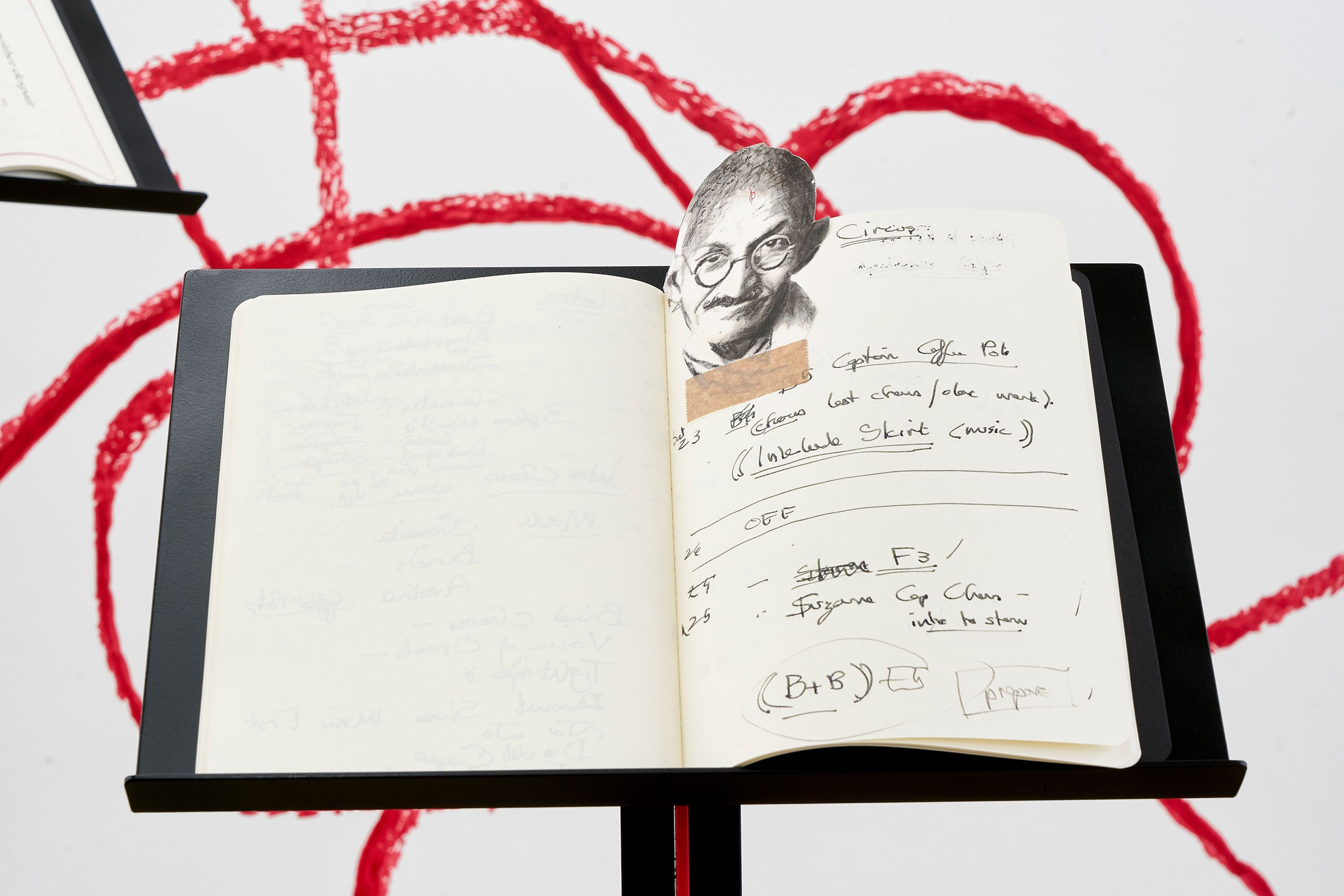

Another use is for the actual writing down of lectures or essays. Those all usually start as handwriting: they may start as a list of possible subjects or topics, and then the actual ‘writing’ starts at some point in the middle of the list.

J.G. You have a solid writing practice. You write a lot.

W.K. I write. I write when I have to. I don’t write voluntarily. Over the years, there’s been a lot of writing, some of which – most of which – I can still read, some of which we have long arguments about in the studio, trying to decipher what I meant when I wrote it. The writing could be for lectures, or for scripts, or for a film: I might jot that down in some brute form. But it’s not journaling or keeping a diary.

J.G. Writing for speaking, writing that’s for something to be said out loud?

W.K. It’s not an interior sort of writing. It is often writing for talking. And this is separate from that which is not a notebook, which is what I call a studio diary. The studio diary is a schematic drawing or diagram that is a representation of every work made in the studio – a list of the work that happens in the studio, week by week or month by month. The studio diary holds a drawing that’s enough to identify what it refers to and it goes strictly chronologically. It doesn’t need to have text because it’s a record. Here’s an example: a record of a series of puppet heads that was made.

J.G. So this kind of diary that isn’t the notebook is not about what you plan to do but rather records what was actually done, what has already been made?

W.K. There might be something conversational listed, like the Coffee Pot conversations, the Whiskey Conversations in Venice and things like that, as well as diagrammatic drawings and relief sketches.

J.G. An inventory.

W.K. Yes, an inventory, just so that people can say, when was this done? And if it was made over the past ten years, you’ll likely find it there.

J.G. I never looked at those when I was there. It performs a different function to the notebook.

W.K. Yes, a very different function.

J.G. The notebooks would be more of a propositional kind of recording. To what extent is the notebook an extension of the studio, an expression of the studio – specifically, the studio as a kind of extended mind?

W.K. I talk about the walk around the studio as the preamble to the drawings, the ‘unconscious’ part of the drawing. And in a way, the notebook is similar. In fact, in some of the Episodic Series, there’s a lot of ‘walking’ in the notebook, physically walking in the studio and placed inside the book. And more recently, just last month, for the first time I made a film specifically in a notebook, for the notebook to be a film. That’s a departure from the notebook’s use. The notebook performed as a kind of studio in its function for that film.

J.G. Does a notebook always travel with you? For example, when you go downtown?

W.K. I would take one depending on what I’m working on at the time. Right before we have our studio meeting every week, I’ll make a list of all the projects and what everyone in the studio is doing. And I’ll usually make a list for myself of things I’ve forgotten – that I was meant to do in the last week, and that I should do this week, and then I check a week later and find that they are still not done.

J.G. Are you saying that you’re aware of the notebook as a site that is going to be drawn into the world?

W.K. Some of it. I’ll know, for example, that these three pages are going to be displayed as part of a film. There’s a big supply of empty notebooks in the cupboard. One is taken out if something new needs to be made. There are ones that will end up very empty, with only a few pages filled. But others, like the first one I showed you – of the lists and notes and things – those go on until right up to the edge.

J.G. If the studio is this place that, so to speak, gets washed down every so often – you know, the work is made, and then it leaves, then it’s quiet for a moment. To some extent, the notebook carries the history of all the things made in it while the studio sees a kind of reset. Of course, there’s a new notebook, so to some extent, there’s also a blank page.

W.K. It doesn’t go away. It’s this infinite record of confusion. Individually, things move out of the studio, say works for exhibition or drawings that might get placed in a drawer, but there are so many different needs of the studio. It’s different to, for example, a painter’s studio where more things might stay the same save for the fresh canvas in front of you. This week we have a piano in for a conductor who’s coming to work on an opera. We had to clear space for that. There are big drawings on the wall that move across to the table for ink and then will go back up onto the wall. It’s a very flexible space. There is an analogy with the note and the notebook.

J.G. So you wouldn’t say that the notebook is a portable studio that you can carry with you wherever you are?

W.K. No, I’m sorry, it’s not quite like that. It is one of the tools of the studio. I do take a notebook with me when I travel. And I think upfront that I’ll make drawings and things like that. But often, I don’t. However, there are notes that I will make in it. Like so many artists, I’m sure you know, I would, in the past, have made a quick sketch of a picture I’d seen or a sculpture I’d seen that I wanted to remember. Now, it seems that one uses one’s phone. And then I’ll come back at night and sometimes go through those notes on the phone and place some reference to them in the notebook, if I can find them.

J.G. Where do you walk when you’re away? Do you walk around your hotel room as a substitute for the studio?

W.K. I don’t ever walk around my hotel room. Perhaps after this, I will. I walk through other cities. I always thought I would draw. There are some artists who have to do a drawing every day, wherever they are, even if it’s a little apple. And I discovered that I’m not very much like that. Very often, there are things that I’ll see in an exhibition while I’m travelling that will excite me, and I’ll make a note of them. Sometimes I’ll make a note in my notebook to remind myself of the exhibition.

J.G. So William, I might have read this somewhere, or maybe it was something you told me: it was about walking on the beach – the beach you visit in the summer – how walking on the beach is very different to the studio, where the studio walk affords this peripheral vision, whereas the beach...

W.K. It’s very different. I’ve often gone for long walks thinking, Oh, well, you just walk to clarify an idea, to let a project settle like swimming a length in a swimming pool. Instead, I found quite often, with that sort of walking, that the ideas I have are a bit like the ideas one has in a dream, which seem so brilliant in the dream, and then you wake up, and you examine them in the light of day and find that they are quite feeble.

The walking in the studio has an endpoint, which is: the gathering of energy to begin. A conversation is another productive way for me to clarify ideas, but just thinking on my own is not a productive way of thinking. Of course, one needs physical activity, but this studio walking is a spur to start the work. This is where there might be the first glimmer of an idea, but then, the idea meets the paper and pen or charcoal, too. Drawing as a way of thinking is also like that.

J.G. If the beach is this long, open space and the studio offers a frame, why is there peripheral vision? Just because you’re looping in your head, or looping in some way?

W.K. In your head?

Yes. I talked about repetition as being one of the things that is an inevitable part of the practice, which is why I described it as a kind of neurotic symptom.

When you look back through the notebooks – for example, at the moment, I’m in the middle of drawing a big tree, which is for the opening sequence of this new opera. And I’m hoping that, as I’m getting further along in the drawing, it’s going to become clear to me how it transforms – not into something different, but how it is able to move in a way that I can’t anticipate yet. Which is both a technical thing, because it is a mixture of charcoal and ink, and you can erase charcoal, but you can’t erase ink. And when it’s drawn all in ink, would it be possible to have an overlay of another ink drawing that can shift and move within it? It’ll take a very practical test to know how the larger idea will emerge.

J.G. Do you have to trust that it just will?

W.K. It will.

J.G. Is there ever a time when it doesn’t?

W.K. Oh yes.

J.G. The less good idea is just a less good idea?

W.K. Well, it has to work. No, not really, but if I have a question, how do we shift from charcoal? We need the ink for the intensity of the drawing. We needed the flexibility of charcoal. Thank goodness, I’ve done this for enough years. I should know all about this by now, but strangely, I don’t. I have to get this tree to the next stage this afternoon. I’m sort of in the middle of the second stage of it. The third stage will be this afternoon. So it will either take off – or not.

J.G. That’s a conversation there between you and the materials.

W.K. Talking through an idea is different. It doesn’t help to talk through an idea for a drawing. You draw.

J.G. I found this in one of my notes. It’s something you said or wrote:

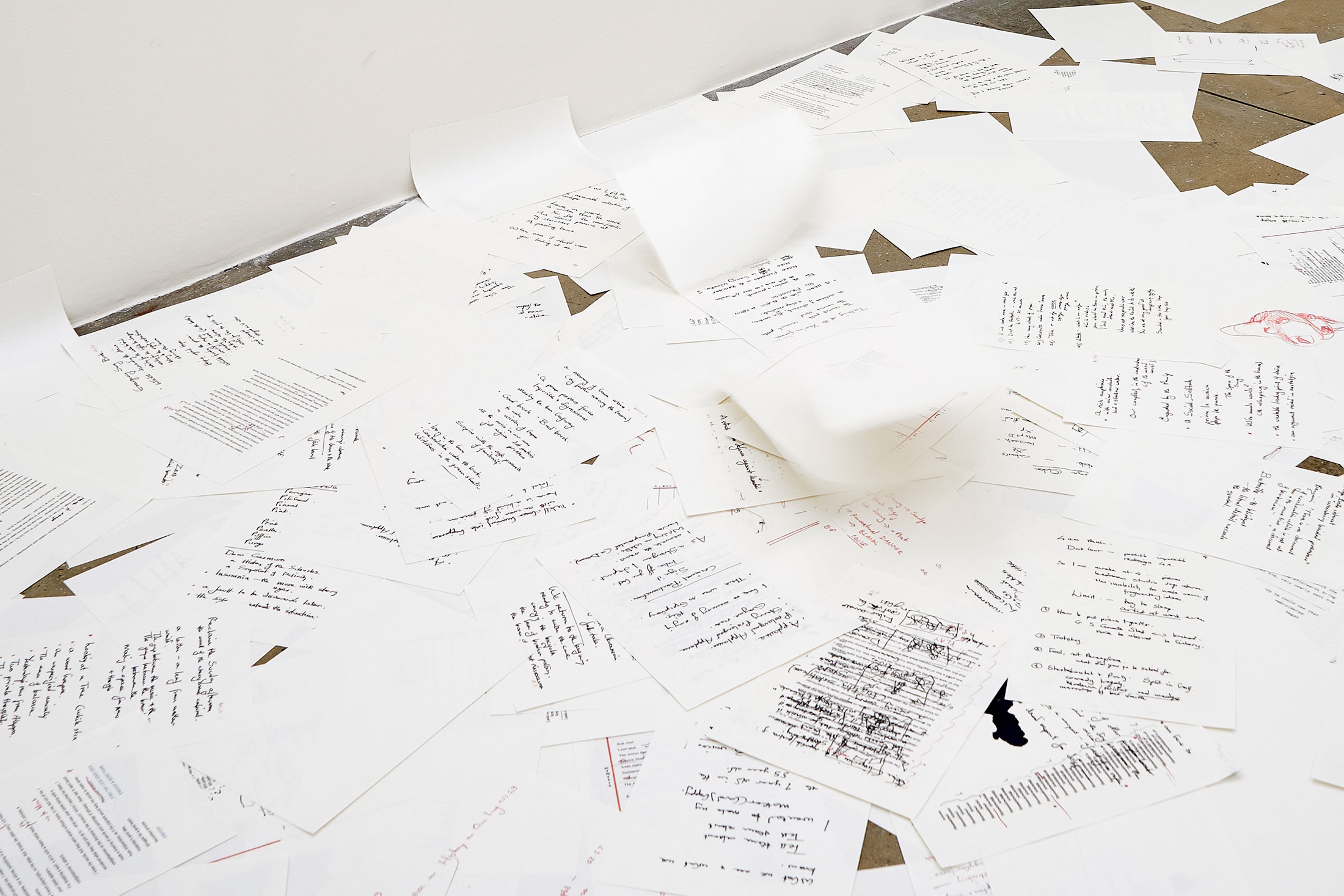

This act of reordering, dismembering and reordering is always the essential activity of the studio. The world is invited into the studio. It’s taken apart into fragments. The fragments are reordered and then sent back out to the world as a song, as a drawing, as a piece of theatre.

W.K. Looking through these notebooks, I’ve discovered how much I repeat myself and how far back so many of the projects go. A phrase that I am using now, I might think, Oh, this is a new phrase. Here’s a new idea. And then, there it was 12 years ago – the same phrase, the same set of ideas. That’s either reassuring or shocking, depending on how you look at it.

J.G. Whichever page you open, there you are. I’m paraphrasing that line of yours. I’ll attempt a silly way of understanding this: there’s an inherent question one has to try and locate an answer to in the world, a question that is being endlessly negotiated. The notebooks reflect this.

W.K. It may feel like a different question, but looking from the outside, it may well be the same question.

J.G. Years ago, I did this project where I digitally tagged something like 30,000 images of my own – largely snapshots, phone images and whatever else – very associatively. If anything was moving about this experience, it was that, inevitably, very different things were pointing at very much the same idea. It was not possible to distil that idea, and yet, I found it oddly relieving to think that there was a question underlying things, a question I couldn’t put my finger on, but a question that was being negotiated through different sets of forms. When you open the pages of these notebooks, do you see that line – are you there on every page? And if so, is this confronting?

W.K. Not confronting, no. I think that’s rather reassuring. Anything can happen on the page because it is still going to be you, right?

J.G. I suppose what I’m asking is, when you open it up and you see these similar queries played back, on the one hand, you’re jokingly saying, Okay, well, you know, I’m asking the same question over and over. But do you see a portrait of yourself through this reiteration of the questions and ideas?

W.K. I don’t. I think there probably is one to be seen, and to avoid looking at. Thinking again, I don’t conceive of the notebooks as a mirror.

Notebooks are thinking forward, not retrospectively.

Notebooks are for thinking, how can this be done? For the job, what is the next practical thing? What are eight ideas for how this might be accomplished? Only in retrospect does it seem like each of those eight ideas points to who you are. They also become a score. So rather, it’s perhaps that I don’t want to interrogate any mirror too closely.

The thing is, every time I’ve tried writing poetry, I wrote it in one of these notebooks. I think those are the only pages I’ve torn out and thrown away, and with great disdain. When I came across those poems a couple of years later, they were so bad. You know, you read a good poem, and everybody assumes they could be a poet. They can see how the poet wrote it – how can that be so hard? It’s just words, not even fillers. When you try to do it, one understands the difference.

When you look in the notebooks and you find a torn page, you now know it was once a poem. Or something, an attempt at a poem. Oh, boy, so bad.

J.G. I found this wonderful line…one second…it’s another line of yours – I don’t know where this one is from, I have it in one of my notes. What does the poem say? Very little, if you understood it. That’s you. And then there’s a counterweight to this. Near the opening of the Norton Lectures, I think, your dad says to you, don’t be discouraged. This is the line: don’t be discouraged, he urged, you’ll be understood in the end. He’s making this proposition to you of being, in some way, understood. But it does feel to me that, at least across the matrix of things, there’s a proposition that poetry isn’t understood. Apply this to what is poetic in the arts, what need not be understood. How do you situate between some kind of knowing and sense and nonsense?

W.K. The hope is that the accumulation of nonsense adds up, not just to nonsense, but to saying something about the world. I like the story about Leonard Cohen reading his poem on a radio programme. The interviewer asked Cohen if he could please explain what the poem means. And Leonard Cohen said, Yes, I can. And then he simply read the poem again. This suggests perhaps that the poem really does not mean very much in itself or, rather, that the interpretation is never the same as the poem.

J.G. I would say that in your world, you construct the conditions for engaging with poetics while not demanding that one must interpret. There’s a comfortable negotiation, an invitation to allow associations to emerge.

W.K. The wish is always that the work is more than that. The poem should always be more intelligent than the poet. The poem should know things that the poet doesn’t yet know, which he discovers when he’s written the poem.

J.G. That’s the surprise, both for the artist working and for the viewer: those associations you hadn’t anticipated, which are deep in the work. Is that some measure of whether you feel your work is successful – whether it surprises you?

W.K. To some extent, yes. Certainly, when it doesn’t surprise me, when it looks, Oh, how pedestrian, it’s a measure of a lack of success. It works both ways.

J.G. And then, William – this is a crude reduction and I apologise, but for the sake of finding a way through to the title of the exhibition: I think I joked with you about this once before, a challenge to stand on one leg and say what your practice is about. Like an elevator pitch. You’ve got to be succinct. I’m thinking of two parts to your ‘history’ on one leg: the first is your engagement with complex historical conditions in a way that allows time and space to think through them. Using your materials and tools, you render other worlds that afford association, access and engagement without being prescriptive. Then there’s another aspect, which is you as the character, starting all the way back in the Soho films. Then there’s the Norton Lectures performance moment where you begin to present as overtly you in the performance lecture and in the studio. The dynamic of you the artist, engaged in a historical moment and you the character, and the role you play as the artist. How do these come together?

W.K. When I appear as a performer or a character, it is almost always in the context of the studio. Not so much in the first Soho films, but in the Episodic Series, for example, they’re all strictly inside the studio, never getting outside of the studio. That’s a subset of questions about the world. That’s a subset of questions about making sense of the world in the way that the studio does. It would be stupid to employ an actor to perform the artist doing it, so I use myself. I’m sure there’s a defensiveness of being in the studio, keeping the self in the studio, that comes with a sense of awareness of what it is to be a political actor out in the world from my own experience as a student within the cultural politics of a country. Twenty years ago, I was least effective in that, and acknowledging that ineffectiveness meant that whatever I had to say about the world, it would be from the studio, rather than making statements outside. And each time I’ve shifted and been outside the studio, the experience has made me realise very quickly that the studio is where the practice is at.

J.G. When you say that the studio is a safe space for stupidity, what do you mean by that?

W.K. There are no statements which are considered stupid in psychoanalytic spaces. You give all things – any statement, any association, anything that bubbles to the surface – the benefit of the doubt in the belief that it doesn’t come from nowhere, that it isn’t arising randomly, even if you can’t make sense of it at the time – even if it appears as complete nonsense.

The studio needs to be a place where propositions don’t need to be censored before they are made. They can be allowed to come forward. Either they will hold their own – or not.

Not to say that everything that comes up is of value or of interest, but that it need not be shut down in advance. Sometimes, this means a lot of rubbish comes to the surface.

J.G. You create a zone where that’s acceptable and productive. Do the notebooks provide a distinct opportunity for that? When looking back at the notebooks, is there something different happening in there? Your line, for example, the notebook drawings, that’s the roughest line I’ve seen of yours. It looks like you’re just trying to make a note for yourself. Is there a way for the studio to interpret...

W.K. A way to identify the primitive image? Say, instead of a detailed drawing of two lovers, it may just be a diagonal line, with a finger pointing above and below, enough for me to remember what I was thinking about the diagonal, the horizontal, the vertical. So, yes, sometimes it’s a very brainstem kind of an image – a start.

J.G. How did you choose which notebooks to include in the exhibition?

W.K. We veered, I suppose, towards the majority of them being quite legible, rather than the illegible handwriting – which is fine, but no one is going to spend 40 minutes trying to read a paragraph that you and even I can’t quite make out. In a few sections, we’ve actually created transcriptions of the handwriting that will be stuck alongside the illegible parts so that it can be read. These aren’t pure facsimiles. They’re edited – it’s a collection. We’re making a total of 30 studio notebooks out of the 120 or 130 books. And we’ve included the new one, which is the film that is made from inside the book, Fugitive Words.

J.G. Live, like that, drawing for the camera in the book? Am I correct in saying you drew and erased as you would normally...there were no pre-drawings before those drawings?

W.K. And the pages are adjusted under the camera.

J.G. They were rubbed out and left, just like that.