We all have other jobs. That is how we are able to afford the idea of Under Projects as a non-commercial space. The amount of capital needed to begin a project space is so high that it seems ridiculous to be an experimental space when you could be entrepreneurial instead. Part of the reason that Under exists is because of the pandemic. Rents became more affordable.

– Mitchell Gilbert Messina

This assertion by Messina during the Common Roundtable (8 June 2023) underscores the central issues at play as we try to understand the economic conditions and imperatives which contextualise the creation of project spaces, and the financial models used in response. In the past, art was framed as a refuge from the market. However, the art world and the art market are intertwined, as demonstrated by the economic and cultural dominance of commercial art galleries and art fairs, particularly in the South African context. The organisers of project spaces rarely have an all-encompassing, ideological resistance to the idea of the art market. Many of the artists who have contributed to the project spaces included in this study have worked with commercial galleries and art fairs. The field of study regarding project spaces is largely centred upon activities in the West – countries with governments that actively deploy public funds within the cultural sector. This means that with enough administrative work and appeals to bureaucracy, their financial obstacles are relatively surpassable. Though the post-apartheid South African government has produced reports since 1998 which “identify music, publishing, and particularly the craft and film sectors as suitable for the task of rural and urban job creation,” contemporary art has been of little interest. Any appearance of interest has been undercut by the historic inexperience in the creative industries of the politicians leading the Department of Arts and Culture, as well as the department’s 2019 merger with the unrelated Department of Sport and Recreation. There is of course historical context: ‘Fine art’ has been perceived as a bastion of whiteness and wealth in South Africa, inaccessible to the majority of the country. However, this attitude from the government is self-propagating. The lack of public funding limits who is able to participate meaningfully in South Africa’s art worlds – both mainstream and alternative.

Most project spaces are at least partially self-funded which is why, as noted by Messina, the only way to afford the idea of a non-commercial space is to have another income stream. That may be a job as a professional artist or – more likely – as a studio, gallery, or production assistant, or in an adjacent, more resourced industry like film or advertising. For those without a financial safety net, expending the resources of time and money with little hope of a return is a significant sacrifice. Describing his time co-running FIG in Johannesburg, Werner Vermeulen said, “You become a sideline hustler, you do anything that comes to you.” For him, that meant working on Johnny Clegg music video shoots, assisting Wayne Barker as he designed the set of Dali Tambo’s People of the South talk show, and crafting and selling beaded bowls and jewellery which eventually ended up in Vogue magazine. “That's how we survived. You just took whatever jobs you could get and you had to kind of divorce yourself. There were things that we didn’t exhibit and didn’t even put our names on.”1

Periods of economic growth can have a negative impact on the number and depth of project spaces: when the economy is booming, rental prices increase. Emerging artists cannot compete with retail shops for physical space. This problem is present in Cape Town where the supply of property within the city is limited. Ed Young and Matthew Blackman would likely not have had the ability to rent their space directly across from the Kimberley Hotel had the 2007–2008 global financial crisis not happened. YOUNG BLACKMAN’s space at 69 Roeland Street, is now an electronics repair shop.

Similarly, Under Projects was able to secure their home base in August 2022 after the pandemic, when the restaurants at 79 Roeland Street went out of business. Under Projects’ co-founders – Brett Seiler, Luca Evans, Guy Simpson, and Messina – initially secured the space using their personal funds, and the rent was less expensive than it had been before the pandemic, but not cheap (R10 000 a month).

Though Cape Town’s size and spatial politics make starting a project space particularly difficult, Johannesburg is not immune. As noted in the first essay in this series, Newtown had long been a cultural hub for artists via studios and exhibition venues such as the Federation of Black Artists (FUBA), Carfax, and the Market Theatre Galleries. Johannesburg’s city centre had many large, unoccupied spaces available for rent as a result of ‘white flight’ from the central business district to the suburbs. Residence in the city was limited to white people by the apartheid government. Once apartheid ended and black families were able to move from marginalised townships to the central business district, many white families and companies relocated to the Northern Suburbs. This enabled FIG to open their space in Troyeville in the early ‘90s. Even so, artists in the Johannesburg CBD have also been affected by rent increases. In an interview with architect and researcher Sumayya Vally, Keleketla! co-founder Malose Malahlela said,

Newtown was beautiful for artists to reign and create so many things, but when the mall was introduced, when development started, most artists had to leave. They moved into the inner city. That’s how artists ended up at the Drill Hall. I remember the Lister building in 2011, which had a gallery on the top floor. That’s how we saw gentrification coming into the city; they mostly occupied the top floors because the ground floors were still dangerous [laughs].2

Artists are often cited as a harbinger of gentrification within low-income urban areas because their transformation of spaces into galleries and studios changes public perception, attracting real estate developers3. Despite the near constant presence of artistic communities in Johannesburg CBD – Newtown, Troyeville, Braamfontein, Maboneng – the city has had many many stunted attempts at gentrification. The inability of the municipality to lower the high rates of crime and maintain public infrastructure are often cited. Despite a R10 million redevelopment project by the Johannesburg Development Agency and continued negotiations with the city and the Department of Public Works4, Rangoato Hlasane pointed to “issues of occupational health and safety” at their venue in Drill Hall for Keleketla!’s relocation to the King Kong Building in Troyeville. This instance of government neglect of a publicly owned building is particularly disappointing because Drill Hall is historically significant as a site of protest during apartheid, and had become a valuable resource to the community under Keleketla!’s stewardship.

Under Projects

During the roundtable discussion by past and present project space founders, Messina said that one of his takeaways from beginning Under Projects was that, “it is very easy to start a project space. You just have to be boldfaced and silly and reckless. The hard part is sustaining it.” In an interview with Misha Krynauw, Messina detailed Under’s start5. Brett Seiler had collaborated with his German gallery, EIGEN+ART, curating a pop-up exhibition in a small space on Buitenkant Street, coinciding with Cape Town Art Fair 2022. They still held the lease on the space for the rest of the month, so they opened up the opportunity for other artists to host their own group shows. Between Messina, Guy Simpson, Luca Evans, and other contributing artists, they were able to produce three exhibitions in three weeks. A vape shop took over the lease, but Simpson, Evans, Messina, and Seiler remained in a Whatsapp group, hoping to find a new space where they could continue to organise shows. In a publication which Messina produced for Under during his time as a curator at A4, he included a snapshot of these messages from their group chat:

19 August 2022, 10.03am

“I’ve just walked past this place on

Roeland Street. I think we should

take the lease!” (B.S.)19 August 2022, 10.03–10.18am

“Let’s think about everything and

confirm end of the day” (B.S.)19 August 2022, 12:46am

“I’ve just signed the lease!” (B.S.)

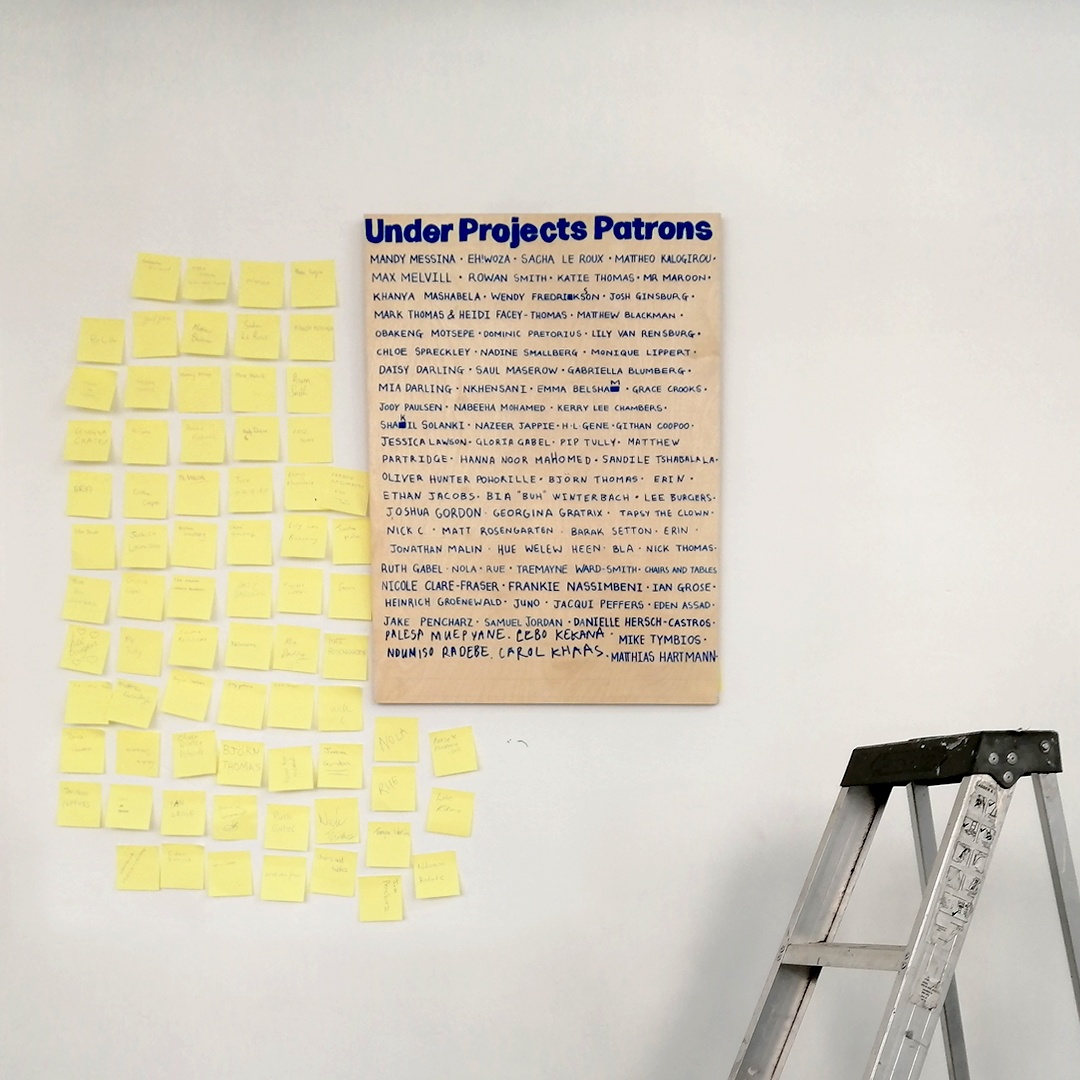

In this series of messages, Seiler exemplifies the brashness Messina deems necessary to begin a project space, moving from thought to action in under three hours. Under Projects’ first event, held on 8 September 2022, was promoted on social media with the title, Help! A fundraising show aimed at recouping renovation costs. After the fundraising event, they thanked their audience for raising enough funds to cover the renovation as well as another month of operating costs. In part, Messina attributes the success of the fundraising campaign to cultural workers’ need for a stronger sense of artistic community, heightened by the isolation and loss of event spaces which occurred due to the pandemic. Performed in this manner, fundraising became more than just a way to inject capital into the project. It became a signifier “that the space is reliant on support from a community that is occasionally willing to float it financially, or contribute works for exhibitions, or volunteer skill sets and services for events.”6 Also crucial to Under’s public identity was its place in Cape Town as a non-commercial space, given the hyper-commercialised landscape of the city’s contemporary art scene. This was done with the hope of creating an environment which fostered more experimentation, an aim which achieved mixed success and which will be explored in further detail in the fourth essay of this series.

Alma Martha

Finding channels of sustainable funding in South Africa often requires familiarity with international, grant-funding organisations. This knowledge is what sustained Alma Martha, founded in 2014 by Juliana Irene Smith and Molly Stevens. Prior to moving to Cape Town, Smith had extensive art world experience studying and working in cities including New York, Lucerne, Glasgow, and Johannesburg. Connecting with Cape Town’s art world, Smith began to conceive of a new project space. During an interview with Smith she recalled her objectives at the time: “It doesn’t need to be a commercial space and I don't want to be a curator, but let's just go play.”7 One of the most interesting elements of Alma Martha’s engagement with foreign cultural institutes for funding.

Arts practitioners in South Africa seem to have a shared sense of pessimism about applying for funding from the government. In the roundtable discussion amongst co-founders of project spaces which took place at A4, it was noted that none of the contributing practitioners had applied for funding from the South African government, mainly because they had little faith that an art project without entrepreneurial aspirations would be understood and supported by them. Regarding foreign cultural institutes such as the British Council, Pro Helvetia, and Goethe Institute, while a few of the practitioners had engaged with them, some were resistant to the stipulations which are often attached to receiving their funding. In order for a project to qualify for funding from Pro Helvetia, for example, it is often the case that a Swiss artist must be invited to South Africa to participate. This is not unreasonable, given that their founding mission is to “support artists and cultural practitioners from Switzerland and disseminate their projects in Switzerland and abroad”.

Rather than being discouraged by these stipulations, Smith communicated with the invited international artists so that the grant money could be shared more equitably with the contributing local artists. “Initially, I got a collaboration grant with Goethe Institute which required us to include European artists in order to secure the funding. And then Pro Helvetia supported two Swiss artists. I was very transparent with the artists from Europe: 'You're getting your flights and your accommodation covered, but the per diems are going to be used to pay the South African artists that we work with, and to make sure that we have things like beer and food for the opening.’”8 Assessing the sustainability of Alma Martha’s approach to fundraising, Smith has said that because they had thoroughly documented their past projects, she anticipated that future funding applications would be successful. However, their space was broken into and all of the infrastructure and material they had accumulated, including the lights, were stolen. She also had changes in her personal life: “I wanted to continue. I didn't expect to leave, but because of personal stuff – I was 39, I wanted a child – it was time for more stability basically.”

POOL

Given the pessimistic outlook that I had encountered amongst practitioners regarding South Africa’s public cultural funding, I thought it crucial to engage with a project space that had been successful in their funding applications. Though we were not able to have an in-depth conversation, Amy Watson shared some important, written insights about her experience of co-founding and running POOL. Founded in 2015 by Watson and Mika Conradie, POOL is described as a non-profit arts organisation which “champions experimental and interdisciplinary artist- and curator-led practice and research, working to develop projects that connect practitioners, organisations and publics across a constellation of creative practices, scales and geographies.” As noted in the previous essay, most project spaces are begun spontaneously through friendships that become collaborations. While that may be the case for POOL, their curatorial, organisational, and administrative expertise is more extensive than most of the projects explored in this series. Discussing the POOL’s funding model, Watson notes that it is “set up as a not for profit organisation with public benefit organisation status which enables it to be tax exempt.” This allowed them to be eligible for more channels of public funding, as well as satisfying their ambition to “model greater ethics and transparency within the arts.” The ‘about’ page of their site makes visible their long history of successfully utilising multiple streams of funding, through local and international, cultural and academic organisations including the National Arts Council South Africa, Arts and Culture Trust, the British Council, Pro Helvetia, and Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WISER).

POOL was originally based at Ellis House in New Doornfontein, Johannesburg – in close proximity to artist studios and Keleketla!’s space in Troyeville. Though Conradie stepped back from the organisation in 2021 to further pursue her own writing practice, it has continued its programming in a new location. POOL was approached by Field Station, an initiative by the City of Cape Town Arts and Culture department to repurpose a former clubhouse in Green Point Park. The project was an invitation to create a programme which engages with the site’s context, welcoming “transdisciplinary practice at the intersection of art, science, environment, community and critical urbanism” – themes which have been at the centre of POOL’s programming. Despite their success in applying for and being awarded funding on a project-by-project basis, POOL’s initial aspiration had been to acquire “multi-year organisational support” which would have allowed them fully dedicate their time to the project, employing a team, paying rent, and covering other organisational costs. Instead, like most project founders in this ecosystem, they have worked in other roles and used their salaries to cover some of POOL’s expenses.

Conclusion

One of the reasons that project spaces prove to be a vital aspect of the art world is their ability to realise new ideas with limited resources. They cannot rely on the tropes of blockbuster museum exhibitions, impressing audiences with large-scale installations or novel technology. Instead, they hope to impress with the scope and depth of their ideas. With their lessened financial capacity, project spaces are more agile, allowing for a greater sense of immediacy and spontaneity than formalised, well-funded organisations. Even so, their creation and maintenance have associated costs. In the South African context, this often requires that the artists use personal streams of income – inheritances, wages from day jobs, profits from art sales, etc – to run project spaces. For many, the dream is to create a space where new ideas can be incubated away from the desires and pressures of institutions and art collectors. This is not necessarily a refusal of the art market, but often a reflection of the realities of the art market: there are many artists and not enough commercial galleries to represent them all. Exhibiting art in project spaces offers an opportunity for it to be seen by dealers, critics, collectors, and curators. Artists are attempting to create “opportunity in the face of limited opportunities as a form of self-determination.”9 As they seek these opportunities, they take risks and make sacrifices. However, as witnessed amongst the examples of project spaces explored throughout this series, personal sacrifices can only be sustained for so long. Beyond running out of money, project founders face burnout, careers that require greater attention, personal challenges, and the need for a greater sense of security and stability. If they continue to run, it may be through reliance on external funding which, as explored in great detail by curator and art historian Kabelo Malatsie in her Master’s thesis, would likely be at the expense of the autonomy which lies as the core of experimental art spaces10. Looking back to the community art spaces of the twentieth century, some – such as Bag Factory and Market Photo Workshop – have continued beyond the involvement of their founders because of their structures. They appoint board members and hire directors, managers, assistants, and interns who collectively manage the administrative tasks required to sustain the programme. When they grow tired of their roles, or outgrow them, they pass the baton onwards. But they also become more institutional, moving away from the spontaneity and flexibility that they had at their inception as project spaces or studios.

The next essay will explore the feasibility of more formalised organisational structures for project spaces, and reevaluate longevity as measure of their success.