Moshekwa Langa

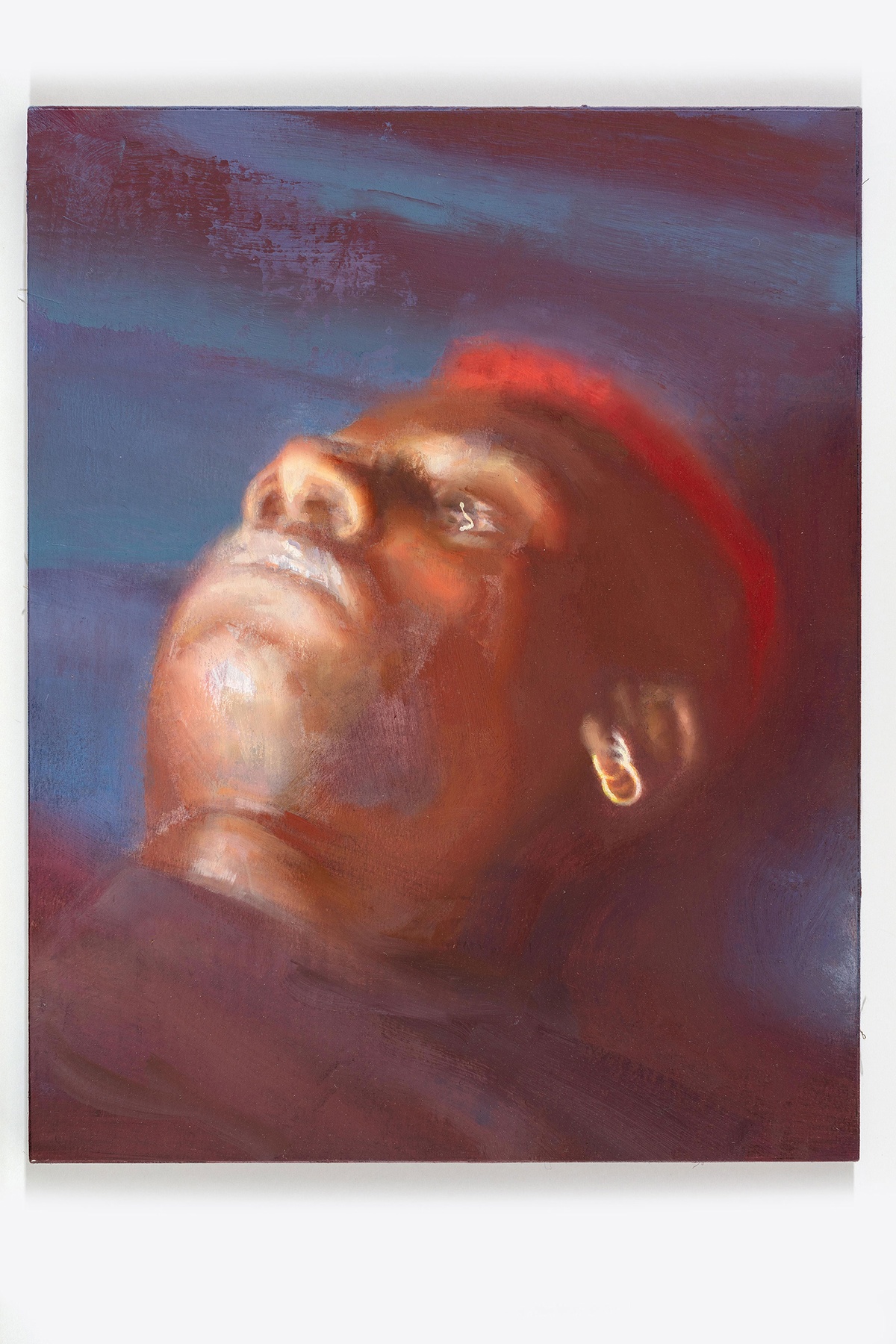

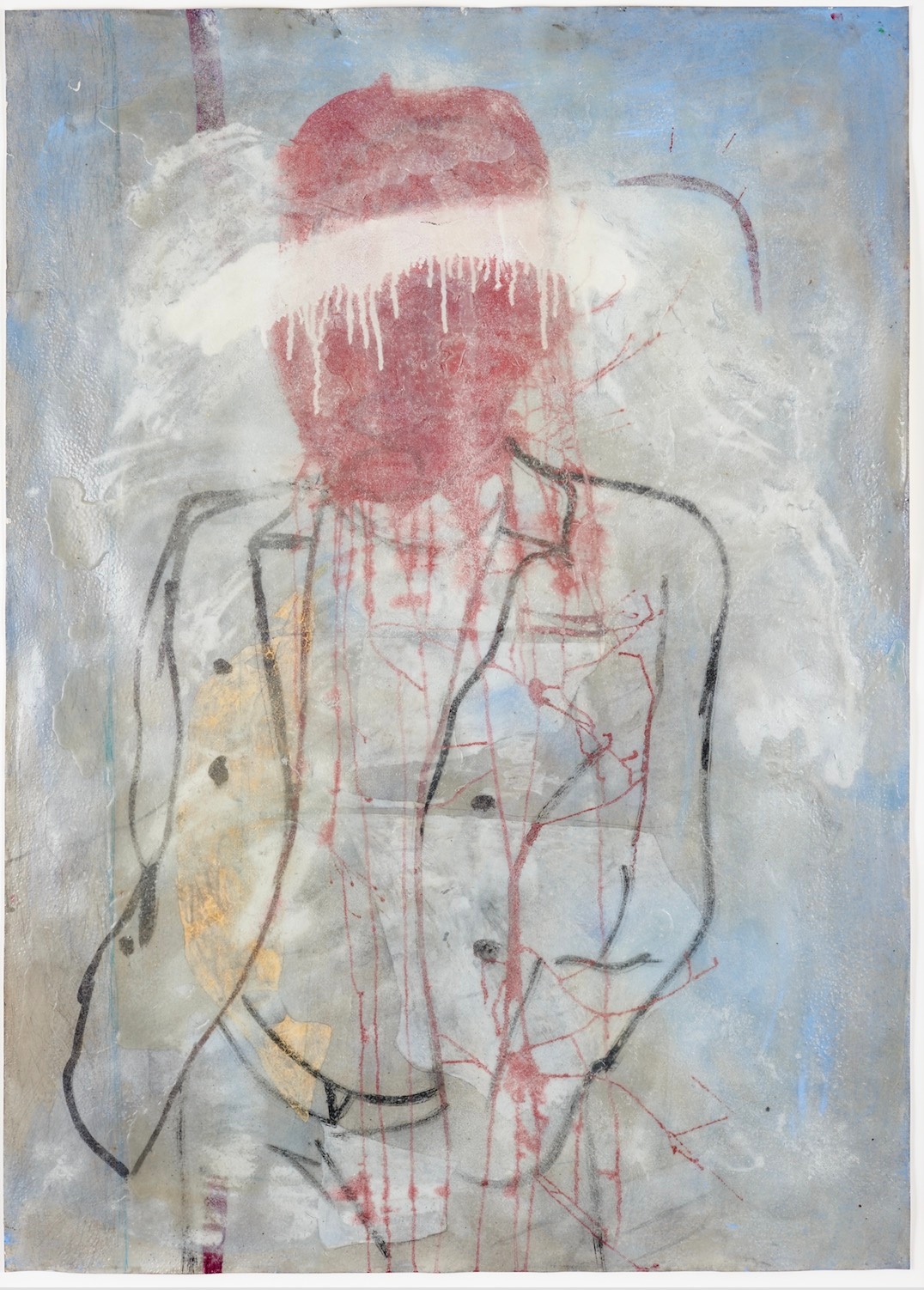

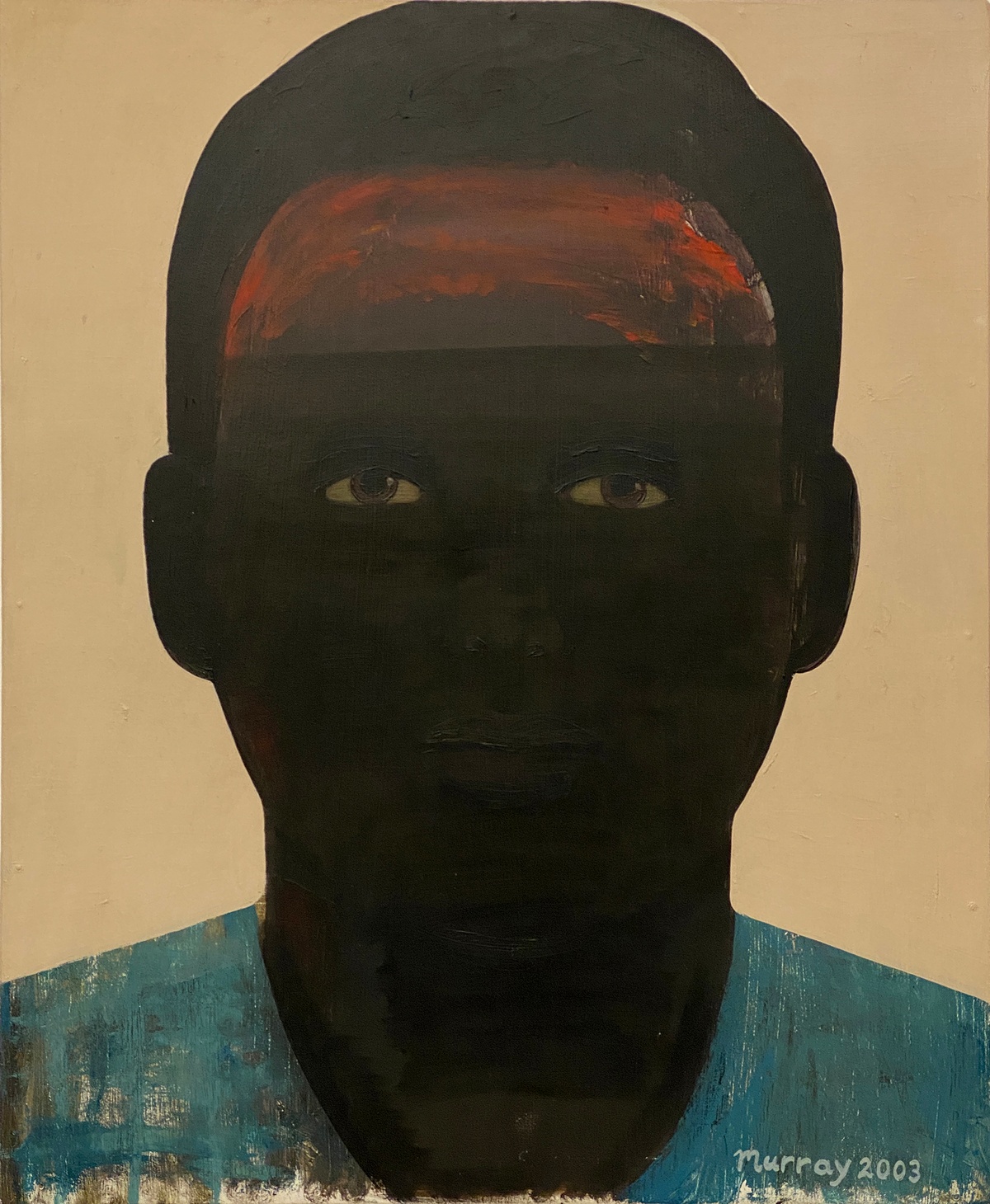

Untitled (Man in hat) counts itself among Langa’s few figurative paintings. The artist works against interpretation, obscuring the image even as he paints it. The man with the red hat is rendered opaque, anonymous and nameless. The white line across the figure’s face reads as a cancellation, as a portrait struck-through. But then, the artist has never been preoccupied with clarity, preferring instead an associative and suggestive engagement with his work. The strike-through is as much a denial of legibility as it is of the painted subject. This resistance is not unfamiliar to the artist’s work. Langa, the critic Ashraf Jamal suggests, “cannot accept resolution of any kind, that his bloodwork, his psychic wiring, militates always against composure, stillness, harmony, truth, and the many other beatitudes we assign to works which we suppose consoling and good for us.”

b.1975, Bakenberg

Ask Moshekwa Langa to speak to an artwork, and he returns a series of detailed anecdotes across time, place, and scale. “I am an episodic river,” he offers –

There is so much urgency around making… I’m always doing things, working out things that are disturbing, difficult, impossible, latent through my hands. When I pause, I have to stop and name everything. The objects are extracted from the river, the outpouring… Everything is shorthand – notes upon notes, confluences and influences. Where am I in that?

Reading Moshekwa’s artworks recalls the stream-of-consciousness style of James Joyce. He recounts his experience of coming upon the latter’s Ulysses (1918–1920), fresh out of high school, as significant. "Later, when I was becoming an artist with a career, I would arrive at places and I would not have had a formal education in art, which was difficult for people who studied for their degrees over four years to accept. But I had read things, and made, and learned. I had poured over Ulysses at least twice, cover-to-cover, developing my vocabulary because there were many things I did not understand, and at the same time I was mesmerised."

The text compelled, beguiled and frustrated the young artist. One can sense, in Moshekwa’s materially limber records of becoming and displacement, traces of the observations – in colour and manner – of Joyce's alter-ego and protagonist in the first chapters of Ulysses, Stephen Dedalus. (Dedalus appears in this novel, aged 22, grappling with early adulthood after his bildungsroman in Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, 1916.) In Ulysses, Dedalus recalls a dream of his mother’s death, a materially rich encounter with wax and rosewood, her breath, that had bent upon him, mute, reproachful, a faint odour of wetted ashes. What is a home without a mother? (2008) mourns one of Moshekwa’s paintings, in which red washes faintly browned resemble the colour of dried blood. Or in Moshekwa’s paint, crayon and watercolour landscapes, one might find Dedalus’ snotgreen sea. The scrotum tightening sea. So too, can one hear Moshekwa in Buck Mulligan's camp inflections (Dedalus' social parrying partner and foil), particularly through the artist’s wry explanations. What? Where? I can’t remember anything. I remember only ideas and sensations, says Mulligan. And Moshekwa – “I have no memory, at least not in the conventional sense,” before listing, with encyclopaedic accuracy, the time, place, and people who were present in the very moment he made a work, irrespective of whether one or thirty years have since passed.

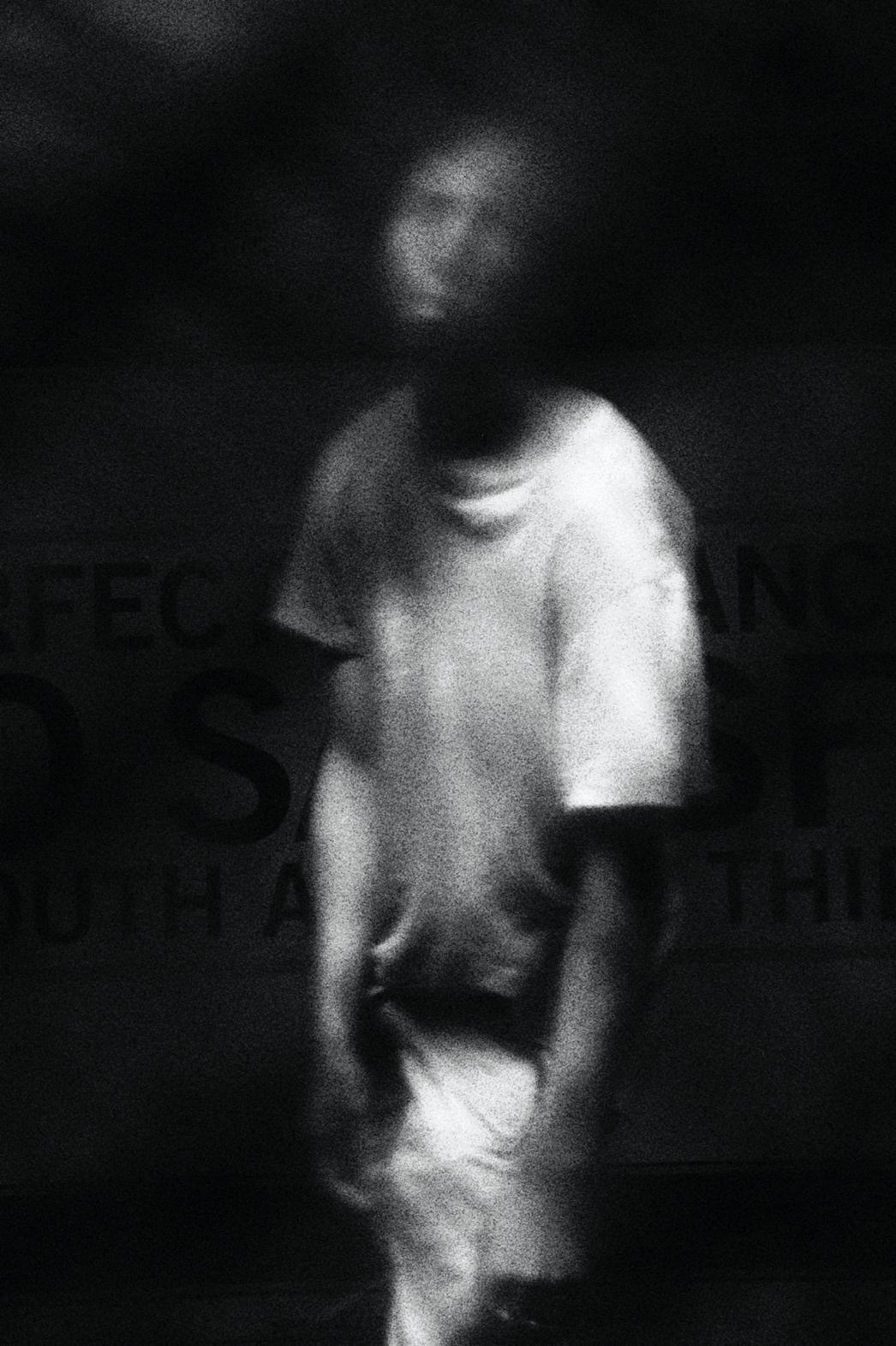

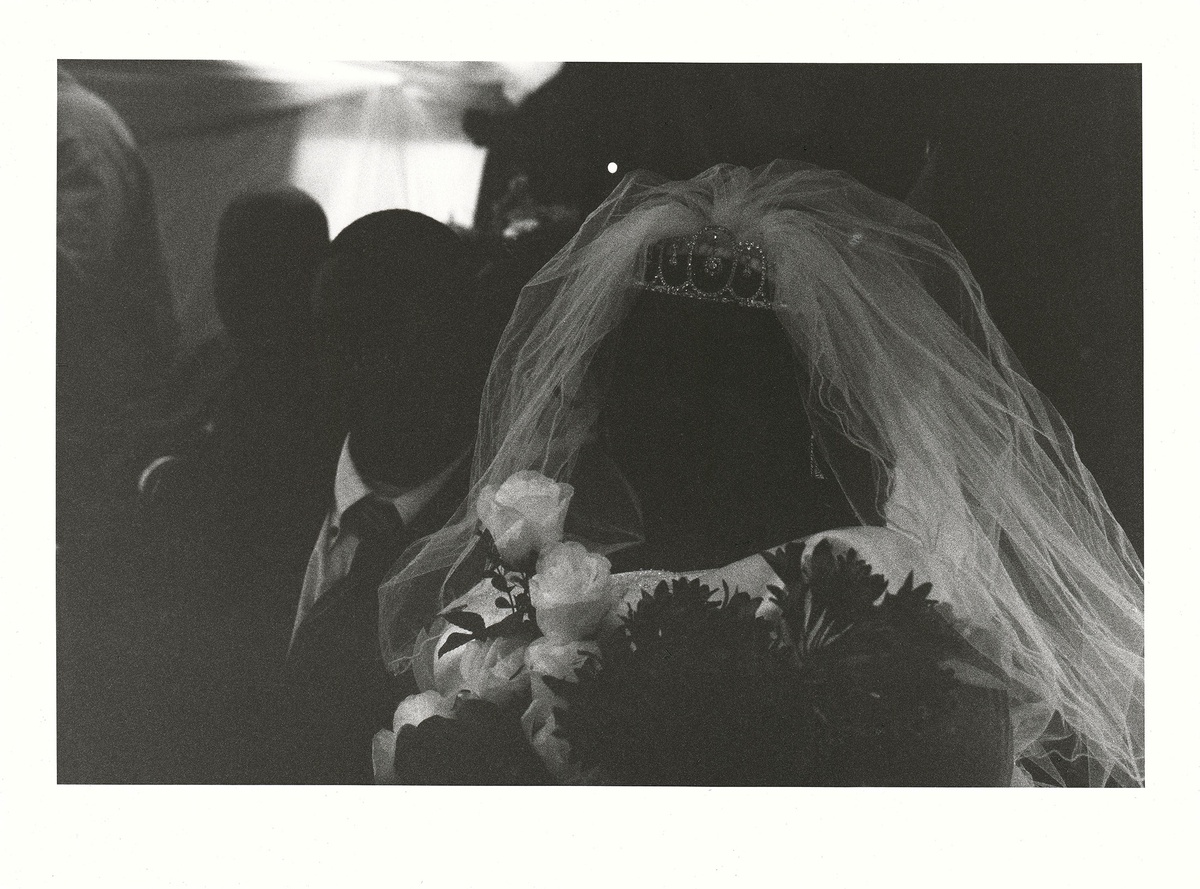

The artwork that first brought him renown in 1995, made from repurposed cement bags, set the tone for Langa’s unfolding practice, marked by a distinct material confidence and economy of means. Untitled, assembled at his mother's home in KwaMhlanga and informally referred to by curators and critics at the time as ‘Skins’, was exhibited at the Rembrandt van Rijn Gallery in Johannesburg and later acquired by the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town. This precipitous success was shortly proceeded by the artist’s two-year residency at Rijksakademie, during which time he participated in biennales including Johannesburg, Istanbul, and Havana (all 1997), a list to which he added in the following decade to include both São Paulo and Venice twice over (1998/2010 and 2003/2009 respectively), Lyon in 2011. Berlin and Dakar followed in 2018. Reading his works as indexes of memory, one can experience crossing over that suspension bridge between the “small communities” of youth into the world overseas. By his own measure, he was at the time “formed but unformed, uninformed,” finding meteoric fame in the post-apartheid optimism of the late 1990s. The experience – of being South African, black, always feeling other, living in a foreign country under the glare of artworld limelight – was a mixed blessing. Much like the title of an early photograph from 1998, he felt Far Away From Any Scenery He Knew or Understood. Having stepped into this astounding number of international biennales so quickly, the funding opportunities one might suppose follow an art career of significant international renown had not yet caught up. By European and American standards, he was 'skint', "arriving with my small bag of tricks and making it all happen,” a singular practitioner, inexperienced to the ways of big cities, of art world opulence, yet gathering and making use of the substances and mediums in his vicinity, whether plastic or cement bags, nail polish, candle wax and crayon, ink, watercolour, pencil, or dust.

This immediacy of working with materials arising from the location in which the artist finds himself invariably becomes its own kind of social record – a gesture towards time-keeping and a subjective mapping of place. Langa’s work is perhaps fugitive, an adjective he has offered up to describe his practice, in that the artist’s subject is more often transitory, of a moment soon passed, a self-portrait of the self in all its flux and complexity.