Frédéric Bruly Bouabré (Cheik Nadro)

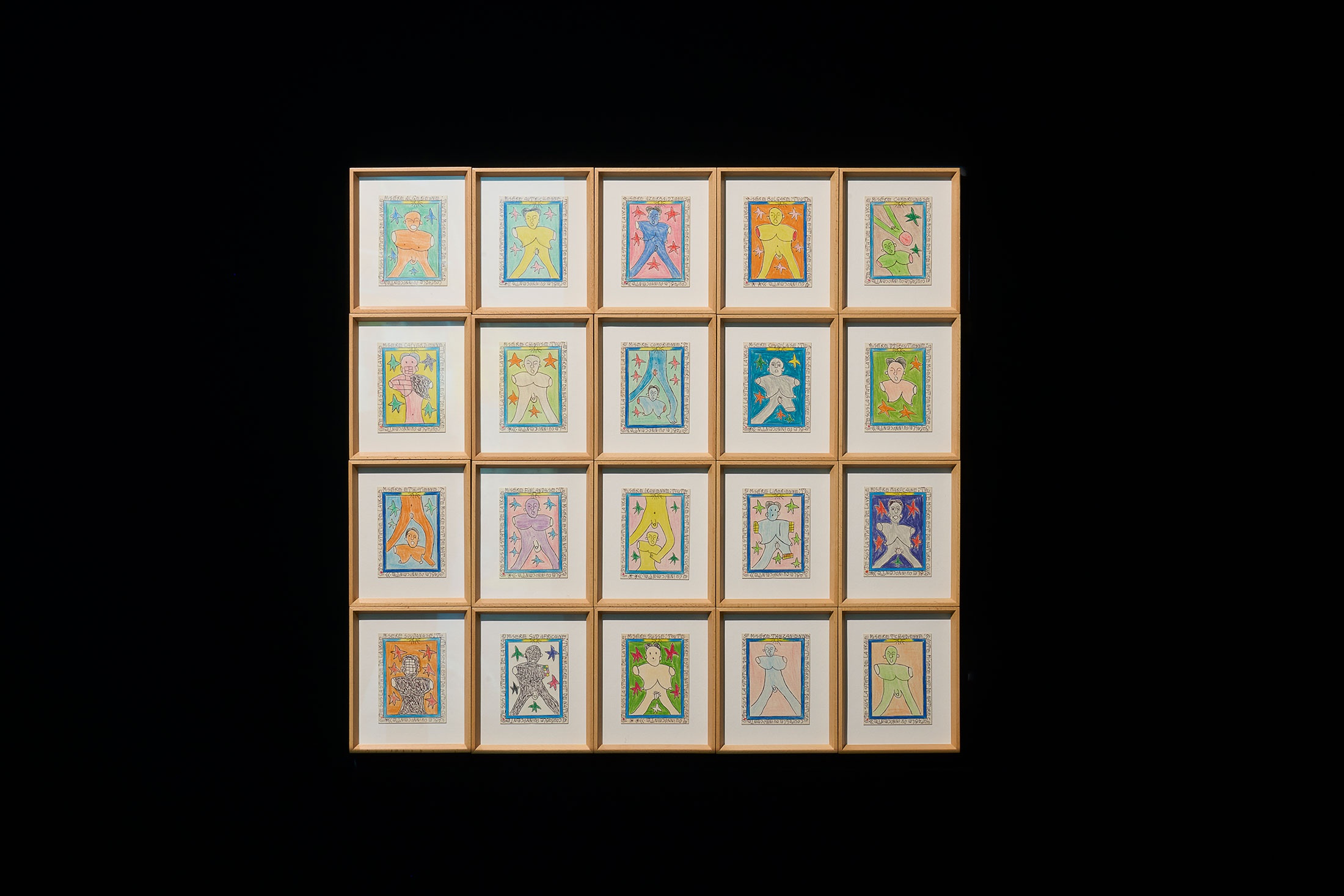

This cycle of twenty drawings on card offers a catalogue of human tragedy, monumentalised as figurative ‘statues’. Each is symbolic of a different country, yet none defines the particular misery to which they refer. All are differently dismembered or defaced, shown naked and wholly vulnerable. Some figures are seen with mouths open in a soundless O; many with eyes closed. The populations of Algeria, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Chad, China, Comoros, the Congo, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Finland, Iran, Liberia, Morocco, Sudan, South Africa, Switzerland, and Tanzania are personified in this sequence. Seen together, one’s attention is drawn to repetition and difference across Frédéric Bruly Bouabré’s rendering of each nation’s suffering. “All misery is either guilty or innocent by nature,” the drawings’ shared subtitle reads.

The cards follow the artist’s established compositional formula: a central image with a pronounced border around which he inscribed the caption in his distinctive, rhythmic script. This pairing of image and writing was central to Bouabré’s taxonomy of knowledge. The text was instructive in intent, a means “to explain what I’ve drawn,” as the artist said. “Writing is what immortalises. Writing fights against forgetting.” The spangling of stars and the spider-like suns seen throughout Je suis la Statue de la Vraie Misère are among the enigmatic motifs of singular significance to the artist, appearing across the thousands of drawings he produced over four decades.

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré’s initial and abiding subject was the Beté. An artist of encyclopaedic inclinations, in 1948 he was divinely compelled by a celestial vision to document, compile and codify his people’s material culture and customs, assuming the name Cheik Nadro, ‘the revealer’. Alongside this role was the artist’s pursuit to document a knowledge or essence that might be considered universal, practised in parallel to his employment as a researcher for colonial French ethnographers and anthropologists in West Africa. Where his early work took the form of intricately detailed, illuminated manuscripts on wide-ranging topics – including the pictorial writing system he invented for the Bété language – from the late 1970s onwards, he began producing the postcard-sized drawings in ballpoint pen and coloured pencil for which he is best known. Included among the many discrete series that comprise his oeuvre are a nearly 450-part Bété syllabary; Stars from my Dreams; an inventory of animal-shaped clouds; episodic retellings of Ivoirian myths; a Museum of African Faces; and a directory of scarification designs from the region. As he wrote to curator André Magnin in 1988:

For us, art is know-how. Art is searching, re-searching, and discovering sublime innocence. Art is professing the frank language that enlightens, rules, explains, and orders the eternal laws of well-meaning reason, that fraternises all the members of ‘great humanity’ in order to alleviate the ‘too many sufferings’ of the individual during his passage on ‘Earth’ en route to a sacred pilgrimage leading him to ‘God’, his creator. Art is ‘knowing how to copy’ the existing realities of nature. Art is knowing how to ‘bring to life’ the good of this world, for reproduction and eternal preservation.