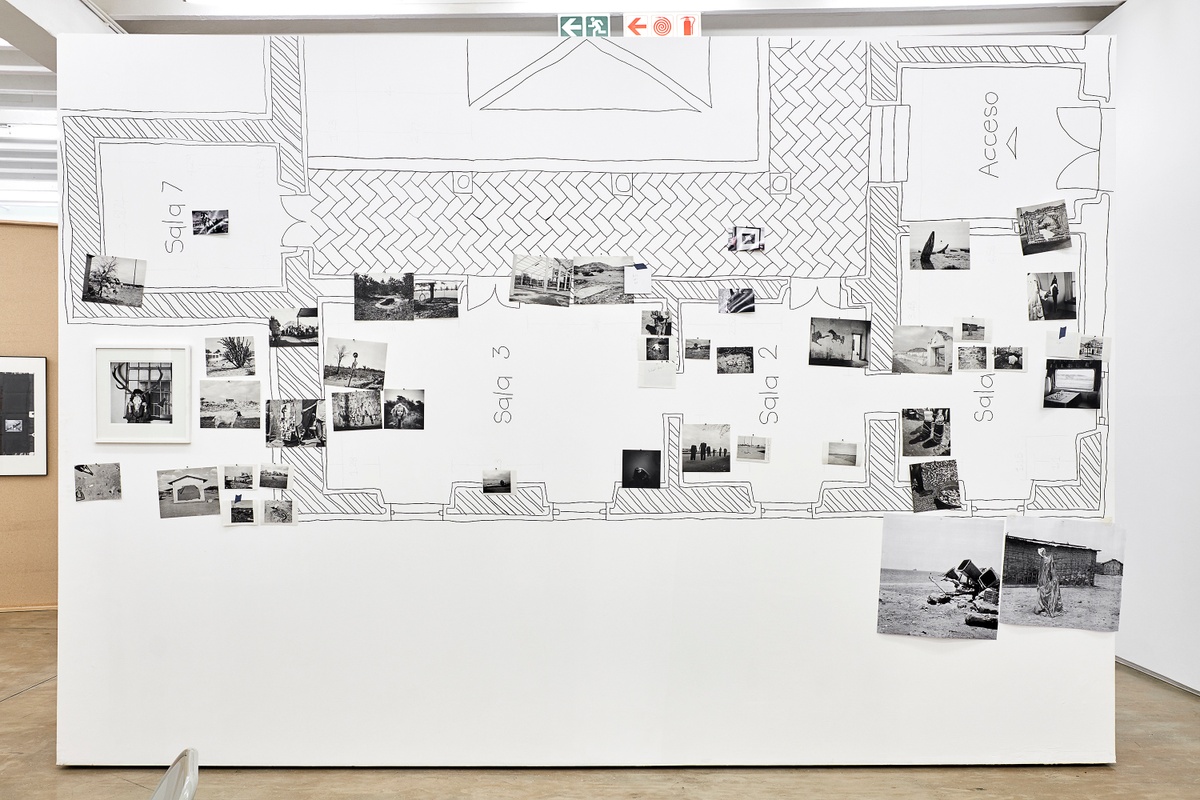

Jo Ractliffe

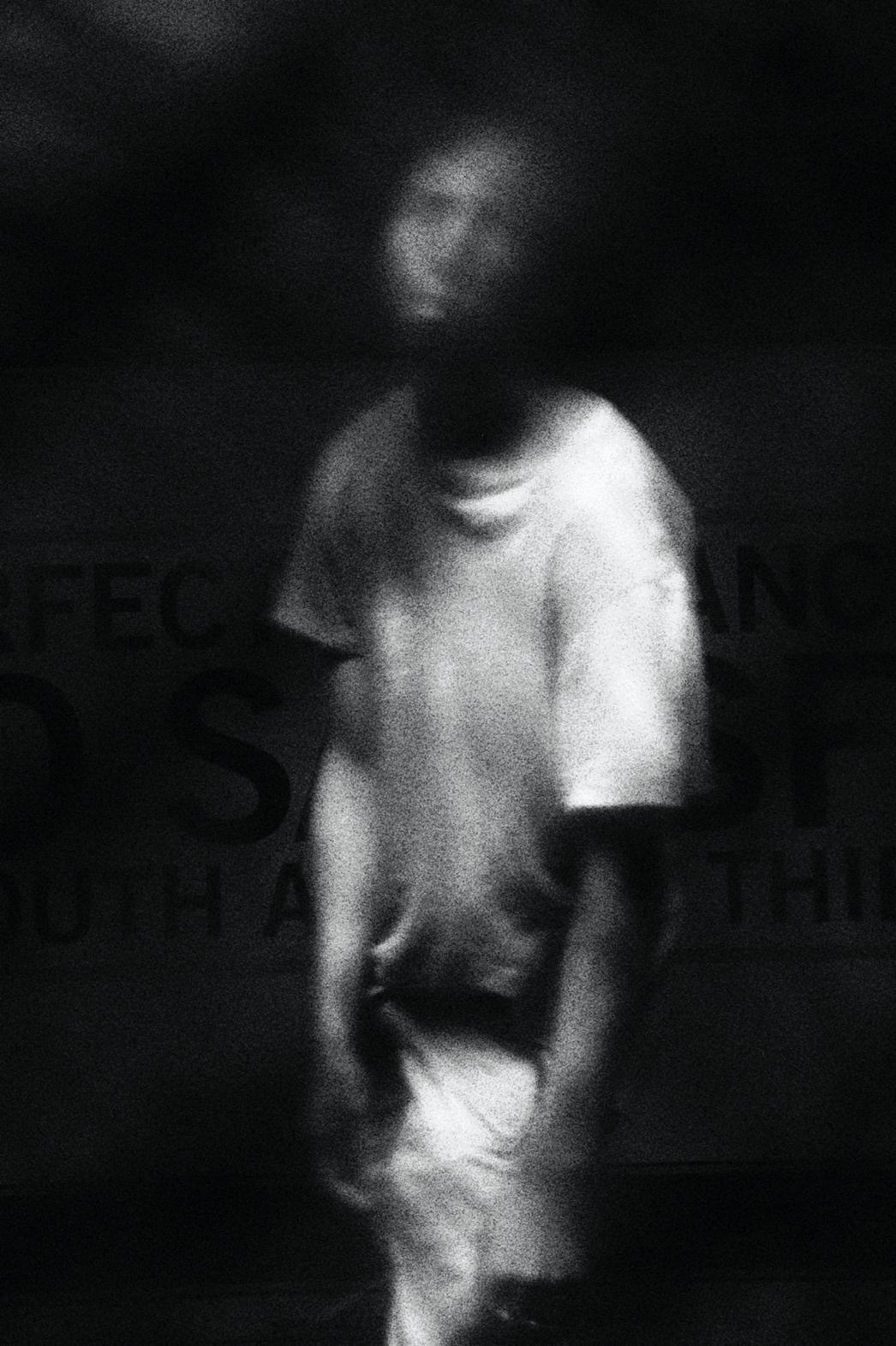

Seeing overalls hung from a leafless tree on the road to Viana, Angola, Ractliffe was struck by their ghostly appearance. “They are the hollow men,” she thought, recalling TS Elliot’s poem. Dark against the bleached landscape, they appeared as spectres of all the lives lost in the then-recent civil war. Upon developing the photograph, Ractliffe found that an airport X-ray machine had made the film hazy, had lent the scene an atmosphere all the more unsettling. “Remember us,” the poem reads –

if at all – not as lost

Violent souls, but only

As the hollow men

Roadside stall on the way to Viana is included in the photobook Terreno Ocupado.

b.1961, Cape Town

To Jo Ractliffe, photography is “largely about guarding against loss,” of giving to memory an image, that it might be kept safe from forgetting. Her photographs more often speak of events past, considering the traces southern Africa’s recent conflicts have left on the land. She returns time and again to Angola, which remained at war for twenty-seven years, from the War of Independence, beginning in 1961, to the end of the Civil War in 2002. In 2007, she visited the country for the first time. “Until then, in my imagination,” Ractliffe writes, “Angola had been an abstract place…it was simply 'the border'. It remained, for me, largely a place of myth.” Absence is inscribed into all her photographs of that country, absence and the persistent presence of war's aftermath. More often, her titles alone establish their significance. Dusty landscapes are revealed to be minefields; rocky outcrops, the sites of mass graves. The atrocities of the past, now mute, are evoked in the bleak emptiness of the scenes she pictures. Ractliffe, preoccupied by all that photography necessarily leaves out, considers silence implicit to her medium. “I try to work in an area between the things we know and things we don't know, what sits outside the frame…these oblique and furtive ‘spaces of betweenness’.”