Thiago Rocha Pitta

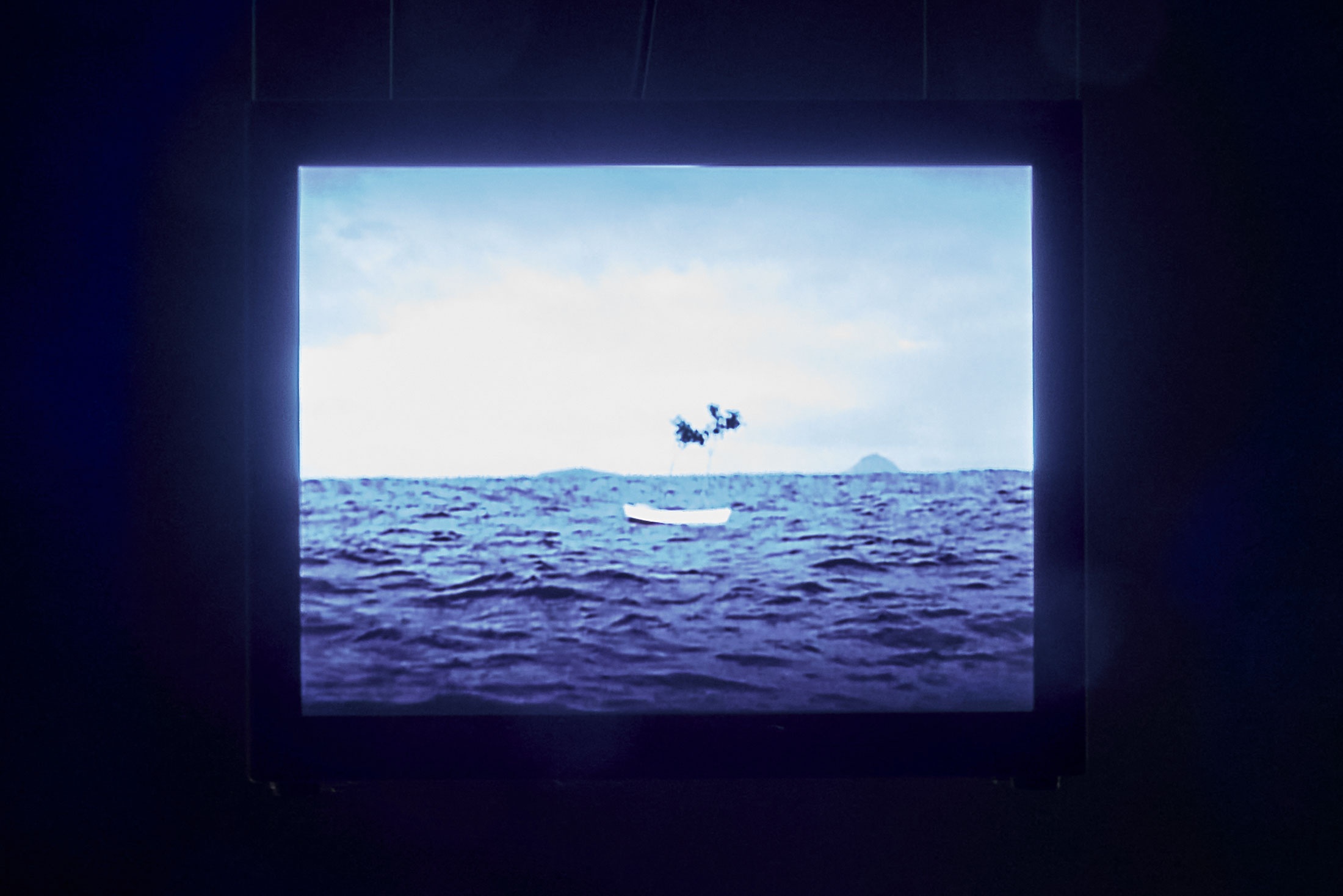

The title, Herança (trans. Heritage) from 2007 is named for the artist’s father. Thiago Rocha Pitta came of age in his father’s studio, where he worked as an assistant. In 2002, Rocha Pitta painted a small jangada boat (of the kind often used in Yemanjá ceremonies) and set it on fire. He titled the work Homage to JMW Turner referencing the obituary by the painter to death at sea. Seeing the work, his father had an idea: Rocha Pitta would pick up a boat and a tree; his father and friends would film it. Despite their intentions, the project remained unrealised. After his father’s death, Rocha Pitta came upon sketches towards the work. Instead of the single intended tree, he planted two. What he (somewhat humorously) refers to as a “horror movie for trees, surrounded by salt water” performs the final collaboration, meditating on togetherness even while cast adrift. Rocha Pitta did not leave the trees to a shipwrecked fate. The boat would have been salvaged by local fishermen, the trees thrown overboard. Instead, Rocha Pitta cast the boat, petrified the sail, set this sculpture in his forest-garden, buried the boat to nourish the soil and planted the trees. Speaking of Rocha Pitta’s practice, Josh Ginsburg said, “He creates a visual tension, bringing things that don’t belong together into proximity or juxtaposition. Salt water and trees. A tree root floating, upended in the sky. These elements seem to have no place being together. Where they touch could be dangerous, critical even, and yet the rubbing leaves a poetic trace where they intersect. One is arrested by the possibility that this might be a survival story of star-crossed lovers, an impossible romance instead of a tragedy. We intuitively know that these things cannot be while remaining invested in their relationship.”

b.1980, Trandentes; works in Petrópolis

In the Atlantic Forest bordered by the Serra do Mar (trans. Mountains of the Sea), sculptures grow among trees in Thiago Rocha Pitta’s garden. A boat – body of a previous work – becomes nutritional compost when buried. Others stand petrified, cast or planted. “We can appreciate the slow decay of things – the disappearing. We grow old and we lose our families and we forget our thoughts and why not? We have got to think about the side of life that is the dying. Art might be longer than life, but it will be brief.” Rocha Pitta’s work invites contemplation of the relationships between humans, their tools, and the environment, deferring attention from bourgeoisie potency in the urban context towards the world beyond that border. He often subverts the idea of a right way up, offering experience in the round – as above, so below. In Atlas (2014) a small, overturned boat adrift on the ocean becomes the container for carrying the weight of a wet world. A mirrored platform Rocha Pitta built at the cliff’s edge features in a collaborative sound and video work made with Paulo Dantas at dawn. Daybreak materialises in the mirror that performs as shard of sky and pool of water. The viewer is in darkness for the first three minutes of the film, light travelling at its pace towards a clarified sunrise. Rocha Pitta offers: “The sound of sunrise is also a picture. The audio is also an image. The sounds reach across the darkness. Giving yourself time, three minutes, is not doing nothing. It is allowing yourself to do less. Contemplation requires this.”

A caretaker of the forest, Rocha Pitta reshapes it, introducing local species, cutting back and removing invasive vegetation, making a case for human occupation that enriches the environment. (A residency in the Amazon provoked the artist’s interest in theorists from the 1970s who proposed that the forest may have been far more widely inhabited – up to 80 percent occupied in some estimations – travelling essential seeds like cacao from Central America and improving the forest’s biodiversity.) “As humans, we are bioselective. We take the environment and we choose from it what interests us and thereby reduce the biological diversity. The Amazon case makes me think that we can be more like bees in the sense that we can pollinate and transform the environment.”