Claes Oldenburg & Coosje Van Bruggen

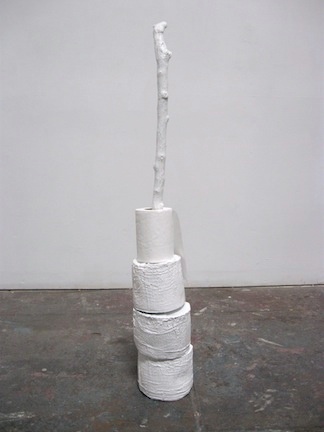

The objects in Scissors with Thread Spool, like those in all Oldenburg/van Bruggen’s sculptures, are perfectly ordinary. Such is the primary precondition of the readymade (at least according to Duchamp): that it be unremarkable and commonplace. Though fabricated rather than found, Oldenburg and van Bruggen’s sculptures followed much the same rule. Made from wood and cardboard, Scissors with Thread Spool appears more provisional than the public works for which they are known. Where such works have about them a heavy-handedness – made of steel and immovable – there is a gestural ease to this sculpture, a material curiosity. It is more proposition than assertion.

b.1929, Stockholm; d.2022, New York

b.1942, Groningen; d.2009, Los Angeles

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen began collaborating together in 1976. The following year, they married. Where Oldenburg had long pursued a career as an artist and was a prominent figure of the New York avant-garde, van Bruggen was an art historian and curator by profession. Their “unity of opposites,” as van Bruggen said – his artistic temperament and her academic rigour – proved a productive pairing. Over three decades, the duo would create more than forty public sculptures as well as installations, performances and drawings. Recognised for their playful humour and Pop aesthetic, all Oldenburg/van Bruggen's works were based on familiar objects made strange in scale and medium – a clothes peg, a trowel, a cherry balanced on a spoon. While some questioned the extent of van Bruggen’s role – believing Oldenburg to be the real artist – the two maintained their collaboration was true. Together, they workshopped ideas; Oldenburg furnished the drawings, and van Bruggen oversaw their fabrication. Throughout their marriage, van Bruggen continued an independent career as a writer and curator, and was the leading Oldenburg scholar until her death in 2009. Asked if he would continue to make work without his wife, Oldenburg replied with some hesitation, “I will see what happens… I am not so sure what direction ‘our work’ will go.”