Diana Vives

A photograph of her young daughter’s hand resting protectively on her deceased grandmother’s beautifully aged ones prompts Diana Vives’ reflections on the body’s relationship with memory and space. Dream visitations from her grandmother soon follow, where trees feature prominently to mark uncertainty about the boundedness of the home. Metabolised through the language of classical myth, the work, for the artist, “asserts a space where recollection, projection, and imagination converge.” In Vives’ telling, her grandmother Zoe Trampidis Grover (1914–2014) was an accomplished child psychologist who rubbed shoulders with the likes of Jean Piaget and the director of a boarding school for children with ‘conduct disorders’. Chafing under social stigma in her private life, her grandmother combined great intellectual rigour with bouts of irrationality. Ultimately, only the appearance of her hands remained familiar as she succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease, with skin that resembled the translucency of porcelain and bones and sinews that suggested the texture of tree bark. The memory of her grandparents’ library, which sparked the artist’s childhood interest in mythology, becomes entwined with the University of Cape Town’s Jagger Library, ravaged by fire in 2021 as Vives pursued her studies at the Michaelis School of Fine Art. Mnemosyne, the Greek goddess of memory and mother of the arts, confronts the tree as a conduit of Promethean fire and creativity with all the potential destruction it implies.

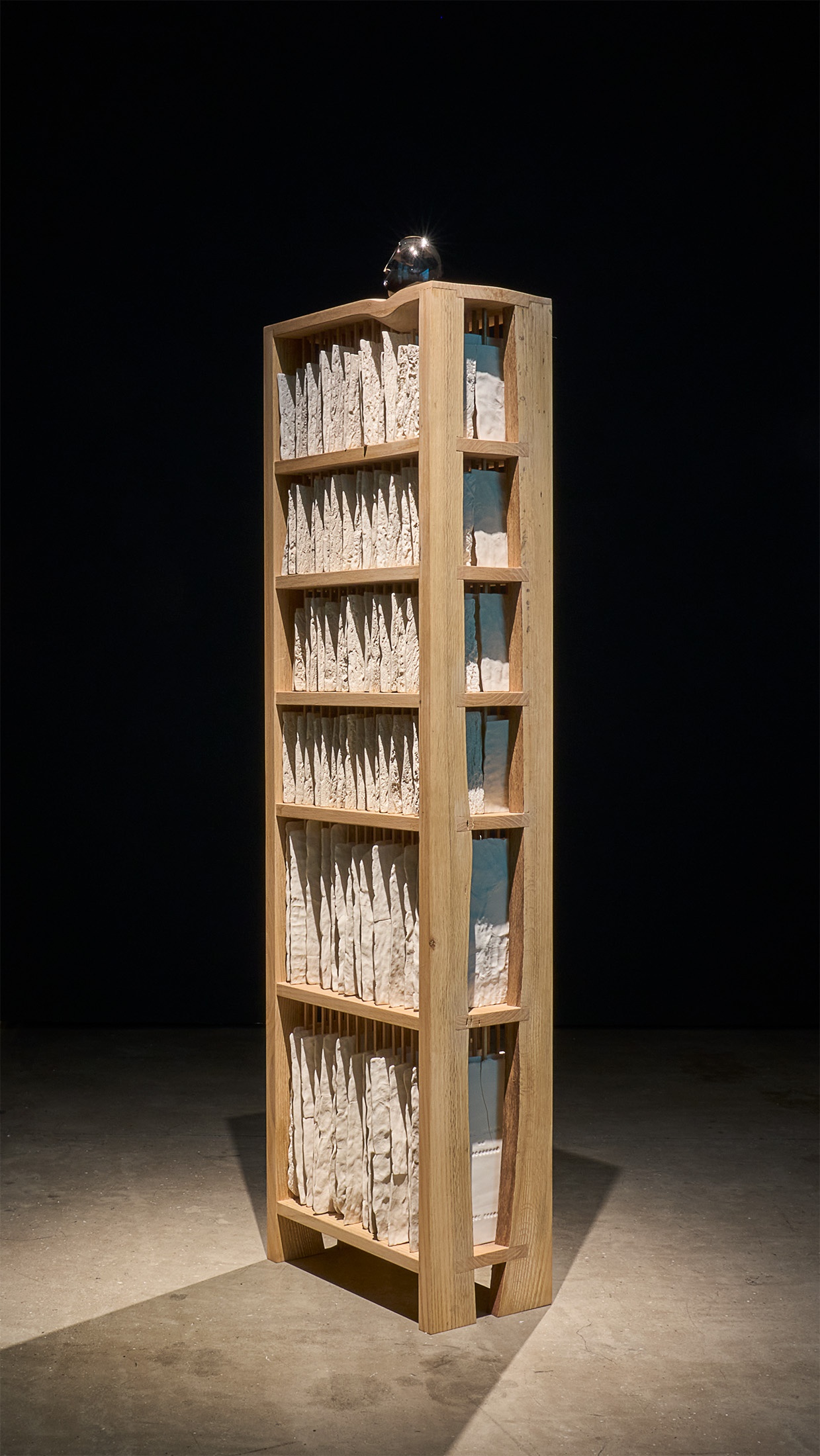

Scaled to the dimensions of her grandmother’s body, The Dream of Mnemosyne’s bookshelf structure invites associations with both intellectual pursuits and the home. The space it delineates suggestively reverses the figure of Louise Bourgeois’ Femme Maison (trans. Woman House) that caricatures the strictures of domestic duty women are expected to bear without compensation. Vives’ gesture of remembrance hinges on the way she unconsciously assumes embodied ways of inhabiting space from her female forebears: “the attempt to retrieve a touch, a voice, or a trace is always just out of reach.” Enmeshed with peripatetic lived experiences, her recollections are inscribed in the pliable medium of unfired porcelain through touch as she traces the bark of a felled centenary pin oak. Vives observes, “remembering a life always involves mapping one form of memory onto another, and such mapping is never seamless.” Fired, the porcelain panels form a collection of 128 smaller, detailed plates and 32 larger and more dramatic “storybooks” that contrast with ink – manufactured from the remnants of books Vives salvaged from the Jagger’s former special collections – housed in a blown-glass vessel that crowns the artwork. If personal and collective memory for Vives intersect “not through resemblance but through shared material processes,” memory nonetheless finally becomes coextensive with writing through the dreamlike medium of seawater.

b.1967, São Paulo; works in Cape Town

Drawing inspiration from experimental uses of materials pioneered by Arte Povera in Italy and Mono-ha in Japan during the late 1960s to the 1970s, Diana Vives’ sculptural practice explores a complex cultural heritage shot through with displacement and exploitation spanning over two centuries. Raised between Brazil and Switzerland, Vives traces her Greek, Spanish and Scottish heritage through a myriad of conflicts from Ottoman-ruled Alexandria in the early 1800s to the Spanish Civil War and fascism in the 20th century. With a background in political science, her turn to the visual arts afforded her the opportunity to wrestle with how these fraught histories inform her subjective experiences. Assessing a world increasingly marked by environmental decline, her nuanced engagement with post-humanist thought and new materialist philosophy finds its expression in storytelling and mythmaking. Walter Benjamin’s pronouncement that “there is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism” echoes in a pointed quote Vives offers from William Maxwell’s So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980):

Too many conflicting emotional interests are involved for life ever to be wholly acceptable, and possibly it is the work of the storyteller to rearrange things so that they conform to this end. In any case, in talking about the past we lie with every breath we draw.