Joel Otterson

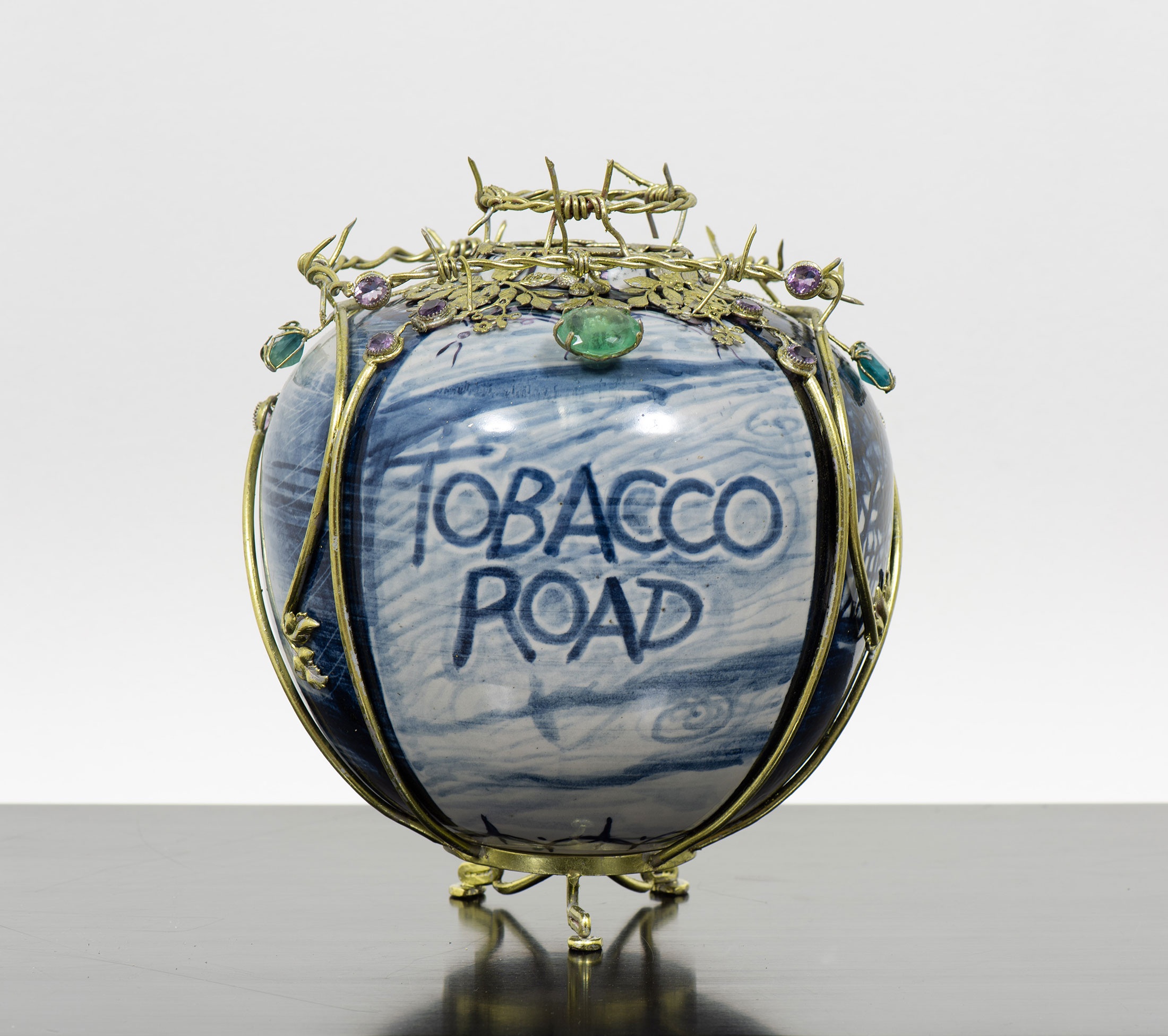

Notwithstanding the phrase Tobacco Road, this work has about it the sense of a church reliquary, its porcelain vase contained in a decorative French ormolu mount, all gold-gilded with Rococo flourishes. Historically, ormolu was applied to, among other things, Chinese ceramics – the intrusion of this decadence onto otherwise beautifully spare objects a visual simile for European colonial ambitions. Here, a reclaimed ormolu mount is augmented with delicate silver pieces and industrially produced copper wiring, from which the object’s barbed-wire crown of thorns is made. The matter of the vase is more uncertain – was it painted by the artist or found as is, Tobacco Road and all, in a junkyard sale? That the phrase recalls the title of John Ford’s 1941 film and the 1932 Southern Gothic novel on which it’s based (a black comedy about a family of Georgia sharecroppers during the Great Depression) is hardly clarifying. Regardless, the dissonance and categorical ambivalence of the work, the flattening of registers of value and its democratising effect, is compelling. Christian martyrdom, French excess, Chinese ceramics, rural poverty – what might all these things have in common, pressed up against one another?

b.1959, Inglewood

Embellishing found objects with filigree, fake jewels, real gemstones, and other such ornamentation, Joel Otterson elevates and re-evaluates the stuff of middle-class American life, from mass-produced household objects – soda bottles, biscuit tins – to their more refined and aspirational counterparts, such as imitation Queen Anne tables, silver teapots and antique glassware. In his assemblages, cultural hierarchies are collapsed, all objects rendered largely useless as discordant décor (one critic described his work as “dec arts from the school of hard knocks”). “I’m trying to make sense out of this complicated consumer-object-oriented world that we’re in,” the artist said in a 1987 MOMA handout. “Hybridization has become the basis for our existence…we’re at a point where things have completely blended together, and you can’t distinguish anymore.” Restaging this confusion of value and proliferation of signs, Otterson’s objects appear as strange artefacts – precious, useless things of indeterminate significance. Yet however camp, kitsch, and maximalist his work, a quiet enquiry into the historical inheritance of material culture plays out in its coincidence of categories. In every plastic Brita water jug, as he suggests, a memory of the classical Greek vessel from which it descends persists. That Otterson’s rise to fame in the 1980s New York art scene coincided with the Aids epidemic further lends these reflections on inheritance an elegiac undertone –

I decided I didn’t want to make monuments to dead people (the job of sculptors for centuries). I wanted to make work about living and what it meant to be alive. At that moment, I started working my way through the house… For over 30 years, I have worked my way through the house and remade everything in it… Being HIV positive myself, given a death sentence at the age of 25 was quite shocking… It has made me give life to forgotten objects. It made me question what makes something have value… The world is full of rampant misvalue…how does the little pinch pot that says ‘I love you Mommy’ on the bottom end up at the thrift store?