Adel Abdessemed

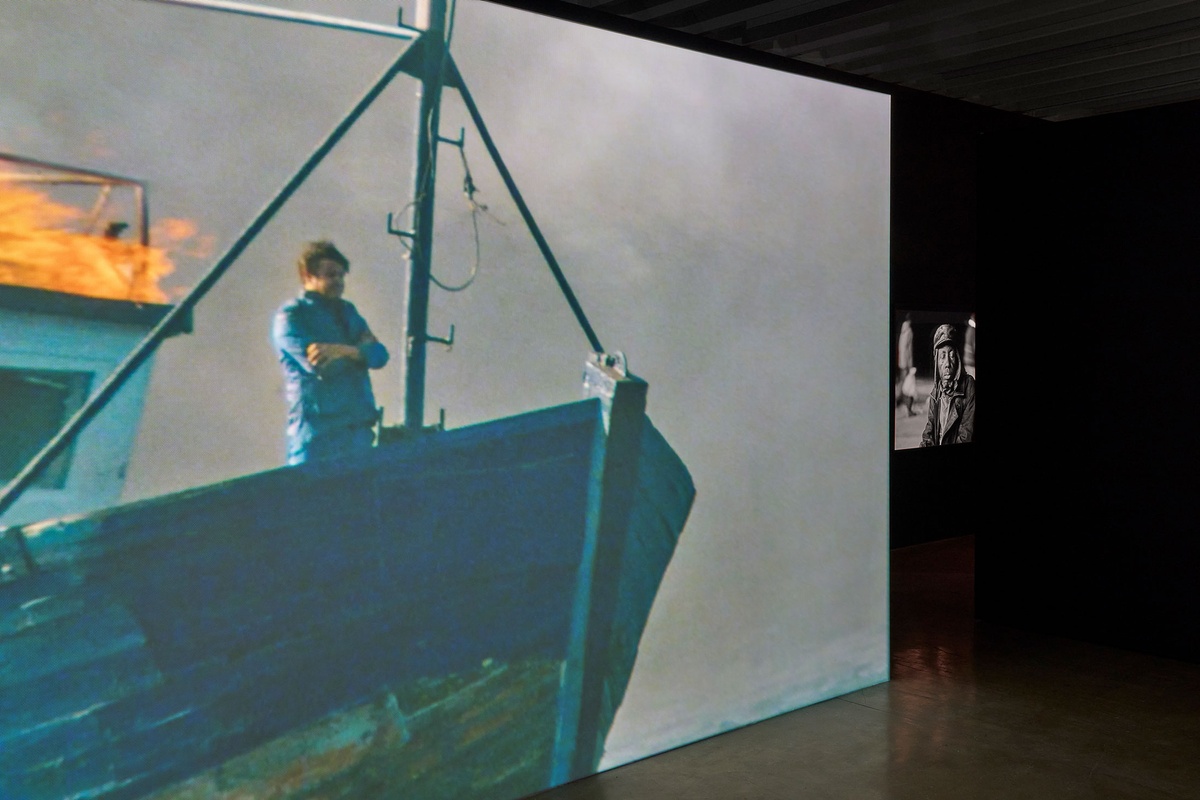

Jam Proximus Ardet, la dernière vidéo (2021) follows on from Adel Abdessemed appearing to set himself alight in the street below his Paris studio in Je Suis Innocent (2012). He refers to himself as “an artist who gets fired up all the time. It’s my drive, really. It is a hot, burning fire. Just like the current world news.” The film witnesses a burning boat at sea. The artist comes into view standing stoically at the bow, arms crossed, gaze fixed, his posture imperturbable considering the blaze at his back. The title is taken from a line in Virgil’s Aeneid (29–19 BC) warning that the house of Ucalegon, an elder of Troy, is on fire. The alert that the neighbour’s house is already alight implies that if they burn, we burn along with them. “Dante chose Virgil, a poet, as the guide into the Underworld,” he says of the philosopher’s decision when writing his Divine Comedy between 1308–1320, to place the ancient Roman poet in Limbo, and have him called on to guide the author through Hell. Abdessemed again calls on Virgil in this title as witness to the hell inflicted on migrants. “When I say crossing I also mean beyond. Going towards something unknown. The boat is really about crossing, not from one horizon to another but from one beyond to another.” Whether the poet in this work brings the fiery reckoning or simply warns us of its coming remains ambiguous.

b.1971 in Constantine; works in Paris

“Up and at ‘em – that’s how you attack an unopened fruit…” Adel Abdessemed practices art as the undertaking of radical and truthful acts. This commitment involves risk. Abdessemed has stoked public ire as well as invited institutional banning. The artist’s exhibition was closed early in San Francisco (2008), a work withdrawn in Lyon (2018). In October 2017, the Guggenheim in New York pulled three of his works from the exhibition Art and China after 1989: Theatre of the World before its opening. Few artists risk separation from both pillars, audience and patron, in the performance of their duty to hold a mirror to society. Abdessemed refuses to look away, however grotesque the reflection. He went into exile from Algeria in 1994 during the Civil War after the progressive director of his alma mater was murdered by militants on the art school’s steps. Relocating from Lyon to New York to Paris, Abdessemed became an international wanderer, curated prolifically onto the Biennale circuit across multiple iterations in São Paulo, Havana, Venice, Lyon and Gwangju, among others. Often, he recycled materials from the immediate vicinity in which he found himself. Aluminium cans were used to make works like the boat Queen Mary II (2007) and his Mappemonde series (2010–2014), the latter which removes the differences indicated by national flags and flattens hierarchies between territories by presenting all in the same colours. Abdessemed believes the artist acts as a witness first, without comment, leading beyond the miasma of fear created by media, politicians, working as much with the intimate as with the very large. Nothing less is possible when living in what he terms the age of un grand cri, “the great scream”.