Marcel Broodthaers

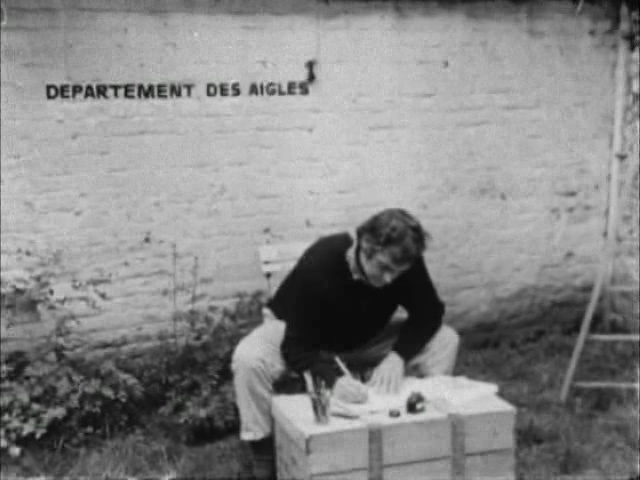

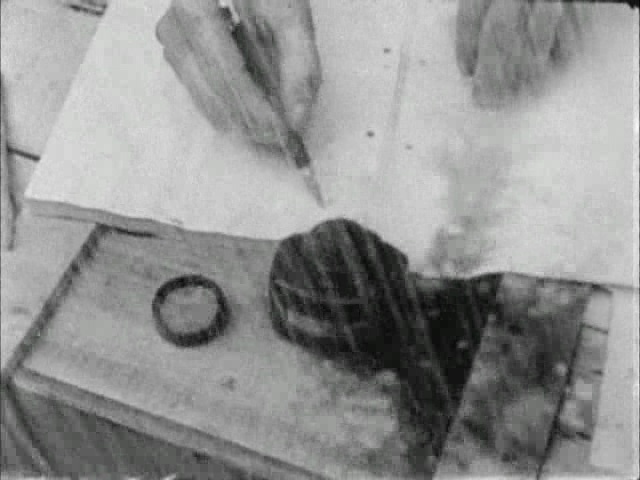

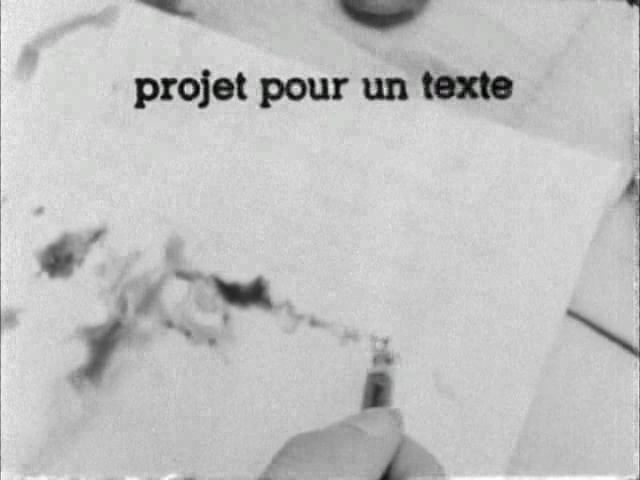

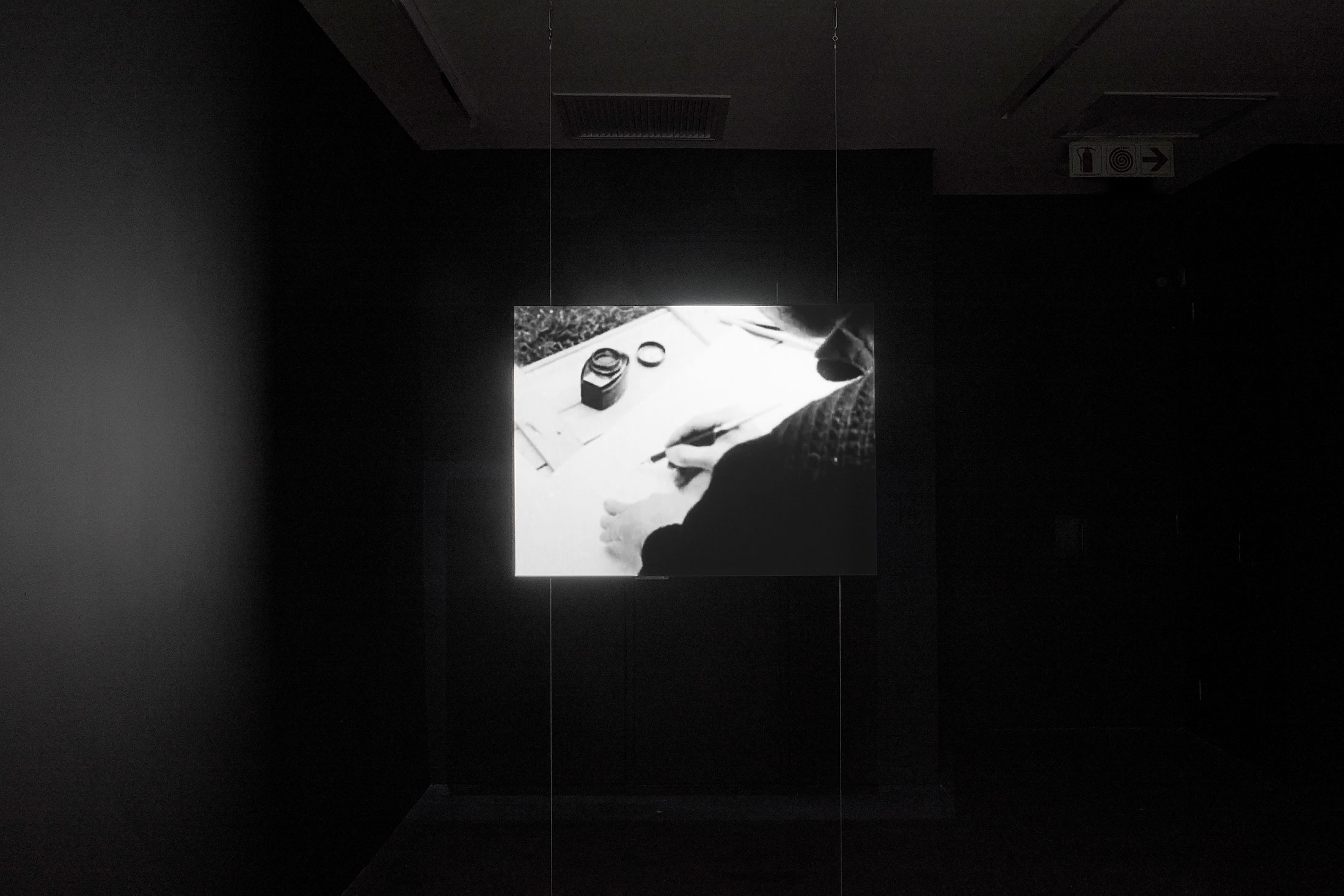

“I hate the movement that shifts the lines,” reads a note by Marcel Broodthaers for The Rain (project for text) published in the Museum of Modern Art New York’s 2016 exhibition catalogue. What then, to make of this filmic conceit of the downpour? The storm upon the artist’s head establishes movement as a fact; the ink is fated to ‘run’. He continues: “Unless I don’t make a film and at the same time accept the value of blank film, the filmmaker’s white page, and pray that others will make it.” The rain is within and the rain is without. Broodthaers does not leave the film blank, nor rely on someone else to do the work but persists to doggedly write with ink-dipped pen into his notebook, awash with falling water, the black pigment lifting from and pooling across the page. It comes to him that a love story, while appealing, would run the risk of advertising the wrong sorts of films – those pornographic, propaganda. This is not a love letter then, to filmmaking. As for conceptual filmmaking, well, he might consider it were it not for the likely outcome: that the film would play the “banal intermediary” subservient to the grand idea. Conceptual art has this effect, one imagines him thinking: the transmission will be flat, the subject diminished, presented as a shadow, the documentary of an idea rather than a thing in and of itself. He ends, “And here I am, cruelly torn between something immobile that has already been written and the comic movement that animates at 24 images per second.” It is perhaps incredible that Broodthaers (standing in here for all writers perhaps, all poets, artists, filmmakers – those poor souls working tirelessly to resolve the resolute gap between word and image) persists in his endeavours. His institutional critique professes to be cynical. Shortcomings, vanities, downright hopelessness, common silliness – the art world is all of these things. And yet, there he remains at his makeshift writing desk, still working.

– Translated quotations extracted from the exhibition catalogue, Marcel Broodthaers (2016). The Museum of Modern Art: New York.

b.1924, Brussels; d.1976, Cologne

The following text lies inside the cover of Marcel Broodthaers’ A Voyage in the North Sea (1973–1974).

Before cutting the pages the reader had better beware of the knife he will be wielding for the purpose. Sooner than make such a gesture I would prefer him to hold back that weapon, dagger, piece of office equipment which, swift as lighting, might turn into an indefinite sky. It is up to the attentive reader to find out what devilish motive inspired this book’s publication. To that end he may make use, if need be, of select readings from today’s prolific output…

After evoking the spectre of the knife (a letter opener in the event that the pages stick together? The taunting critic who lies within each reader?) and tooting his horn as a maker (the droll prolific output) Broodthaers announces: “These pages must not be cut,” frustrating any ambitions to commit book violence that he may just have incited in his reader. Broodthaers was a poet first, an artist only later. His final collection of poems, Pense-bête was published in 1964. Ceasing to be a poet, he could act out the role of poet (writer, artist, filmmaker, curator) consumed by lofty intentions and frustrated by the uselessness of his endeavours. This plays out in such works as La Pluie (projet pour un texte) / The Rain (project for a text) (1969) a film emblematic of Broodthaers’ engagement with the futility of linguistic meaning-making. As an additive layer of complexity, the film is part of Broodthaers’ Musée d’Art Moderne (Museum of Modern Art) (1968–1972) cycle of works, in which he takes up the mantle of a museum curator of his fictionalised ‘Département des Aigles’ (Department of Eagles). Mercurial meaning, the legibility of language, its necessary opacities and imprecisions – those things proper to a poet’s vocation – remained abiding through-lines in his conceptual practice, as did the mutual dependency between text and image. Many of his works perform the redaction or concealment of the written word, any sentences differently obscured or made wholly inaccessible.