William Kentridge

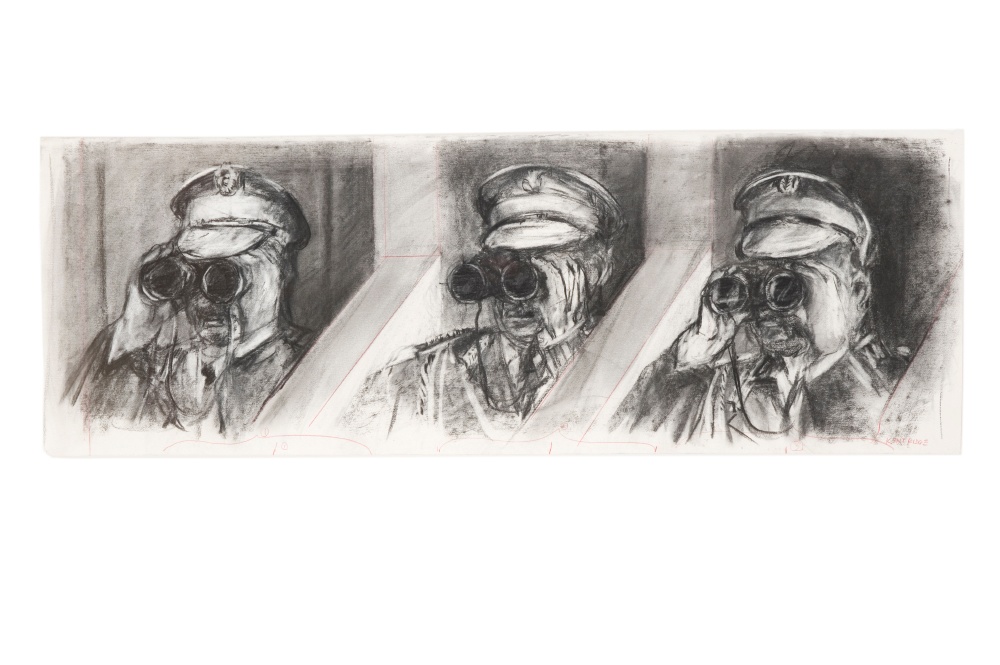

Kentridge’s Tide Table (2003) belongs to a suite of animated films collected under the title Nine Drawings for Projection (1989–2003). More often dark and dreamlike, the films appear as allegories of South African life both under apartheid and after. The artist animates each scene on a single sheet of paper; drawing, erasing and redrawing lines in charcoal to create the movement between each frame. The erasure of past lines remains visible, tracing the scene’s progression from beginning to end. The final images, having served their purpose in each film, later become discrete works. The Generals (from Tide Table) is one such drawing. Above the beach, these three figures keep watch, witnessing the changing tides. “They are kind of like the Three Fates, as it were,” Kentridge says. “Observing, implacable, unmoved.” On the shore below, strange visions coincide. Throughout the film, a sense of unease gathers like clouds over the coast. The water ebbs and flows without pause. With the simplest mark-making, Kentridge transcribes the grammar of breaking waves, translates the movement of water into so many frames per second.

b.1955, Johannesburg

Performing the character of the artist working on the stage (in the world) of the studio, William Kentridge centres art-making as primary action, preoccupation, and plot. Appearing across mediums as his own best actor, he draws an autobiography in walks across pages of notebooks, megaphones shouting poetry as propaganda, making a song and dance in his studio as chief conjuror in a creative play. Looking at his work, a ceaseless output and extraordinary contribution to the South African cultural landscape, one finds a repetition of people, places and histories: the city of Johannesburg, a white stinkwood tree in the garden of his childhood home (one of two planted when he was nine years old), his father (Sir Sydney Kentridge) and mother (Felicia Kentridge), both of whom contributed greatly to the dissolution of apartheid as lawyers and activists. The Kentridge home, where the artist still lives today, was populated in his childhood by his parents’ artist friends and political collaborators, a milieu that proved formative in his ongoing engagement with world histories of expansionism and oppression throughout the 20th century. Parallel to – or rather, entangled with – these reflections is an enquiry into art historical movements, particularly those that press language to unexpected ends, such as Dada, Constructivism and Surrealism.

Moving dextrously from the particular and personal to the global political terrain, Kentridge returns to metabolise these findings in the working home of the artist’s studio, where the practitioner is staged as a public figure making visible his modes of investigation. Celebrated as a leading artist of the 21st century, Kentridge is the artistic director of operas and orchestras, from Sydney to London to Paris to New York to Cape Town, known for his collaborative way of working that prioritises thinking together with fellow practitioners skilled in their disciplines (for example, as composers, as dancers). Most often, he is someone who draws, in charcoal, in pencil and pencil crayon, in ink, the gestures and mark-making assured. In a collection of books for which A4 acted as custodian during the exhibition History on One Leg, one finds 200 publications devoted to Kentridge’s practice. In the end, he has said, the work that emerges is who you are.