Michael Fullerton

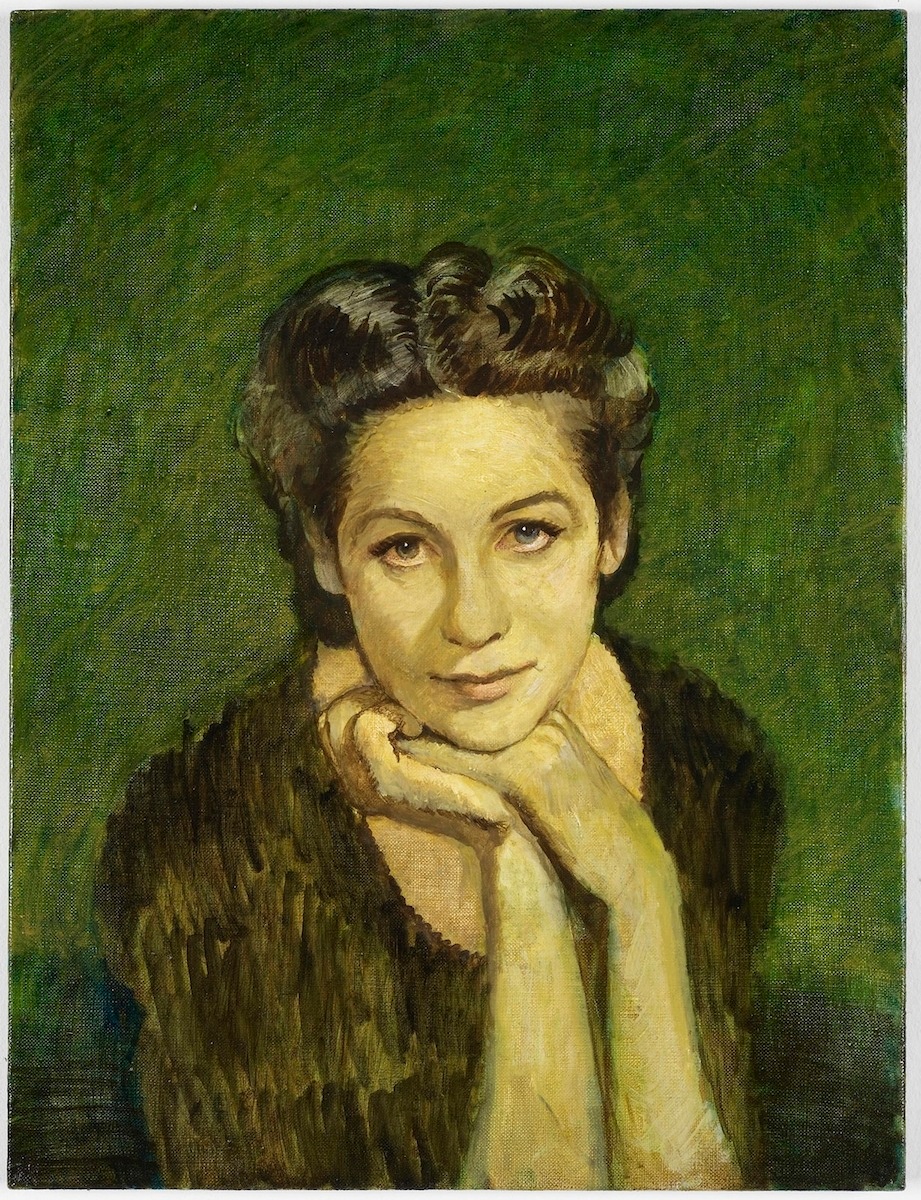

For all the apparent vitriol of its title, The Bitch Messed With His Head offers a tender portrait of a young woman. Painted from a photograph, Mirren Barford looks out towards the viewer, her likeness softened by a romantic glow. The accompanying label introduces her in a supporting role, the lead – one Jock Lewes – being absent; lost in action during a World War Two operation in Algeria. A man of ambiguous standing, Lewes co-founded Britain’s Special Air Service and invented the improvised explosive device that bears his name. Recast in paint, Barford – then engaged to Lewes – plays the part of both tragic heroine and woman of inconstant affections. An extract from the wall text reads:

While a confident soldier in the Special Forces, Lewes’ personal life was dogged by insecurity and jealousy. Upset when Mirren didn’t respond immediately to a letter, he wrote to his brother in 1939: "Have you any news of Mirren? As I have had no reply to my delicately worded epistle, I can only presume that you foxed me with the wrong address, and that you are yourself already engaged to be married to her. I can find no other explanation for her misguided preference for your highly inferior person and her neglect of my well-bred advances."

While Lewes is remembered for his contributions to the battle for North Africa – since tainted by suggestions his of Nazi sympathies – Barford gained posthumous attention for the published correspondence she shared with her ill-fated fiance, Joy Street; A Wartime Romance in Letters 1940-42 (1995).

b.1971, Bellshill

In works of quiet dissonance, Michael Fullerton attends to the politics of seeing and being seen. Technologies with which information is recorded and transmitted are central to his formal engagements; the artist working across such variable mediums as film, screenprint, sculpture, and digital assemblage. In theme, the vagaries of representation are primary, as is the acquisition and proliferation of knowledge. While such preoccupations are perhaps most apparent in Fullerton’s new media works, his oil paintings offer more oblique considerations. Populated by figures painted in the style of 18th-century society portraits, his assorted sitters make for strange company: BBC broadcasters, a defective MI5 spy, the first woman appointed to Scotland’s Supreme Court, a misidentified terrorist, a would-be assassin. Together, they offer a cast – as critic Same Thorne writes – of “representatives from institutions that gather evidence, make judgements or disperse popular opinion,” and the players these institutions have historically misaligned. In addition to title, each portrait is accompanied by an explanatory text, situating the individual sitter in a web of political implications. With a tone coolly matter-of-fact, the museum wall text, too, is a mechanism of knowledge-making, its authority maintained by an assumed objectivity. Shifting between the many modes of communication, from image, object and the written word, Fullerton examines their respective overtures to truth, revealing all to be suspect, and laying bare – Thorne again – “the aesthetics of persuasion.”