Resident: Inga Somdyala

Librarian: Daniel Malan

Curatorial support: Khanya Mashabela

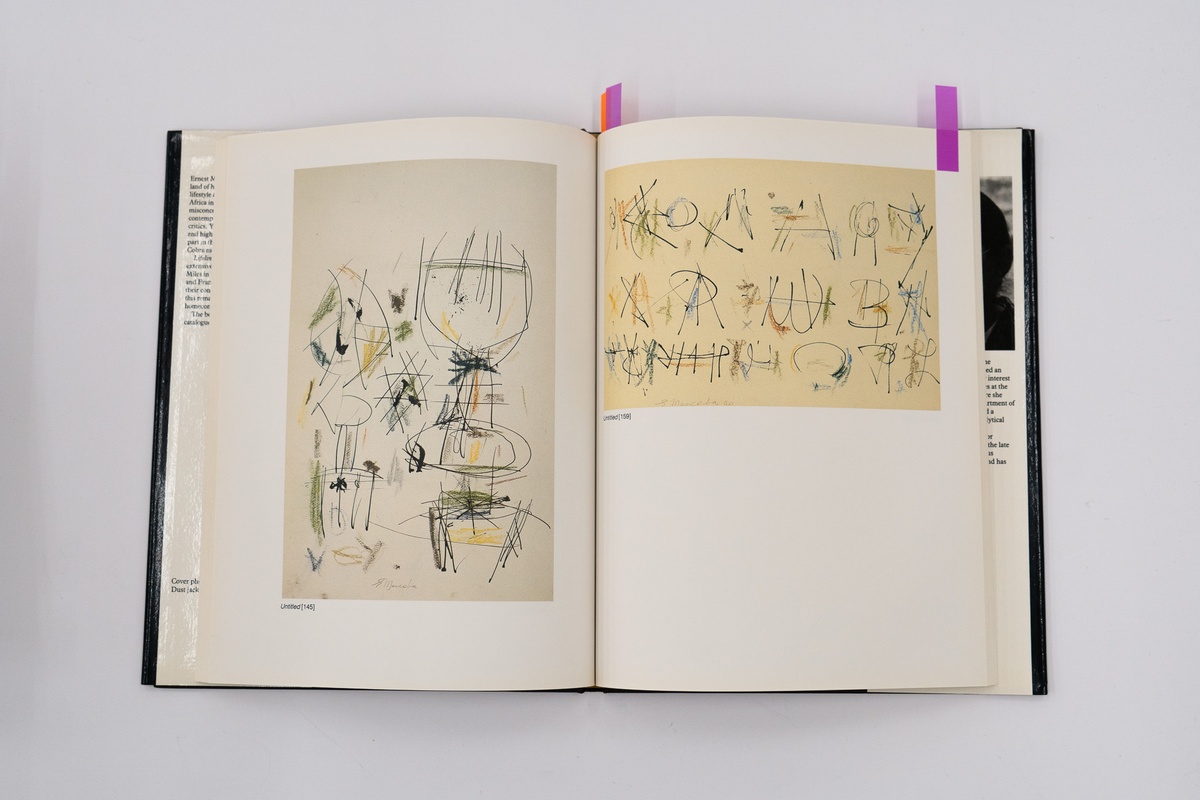

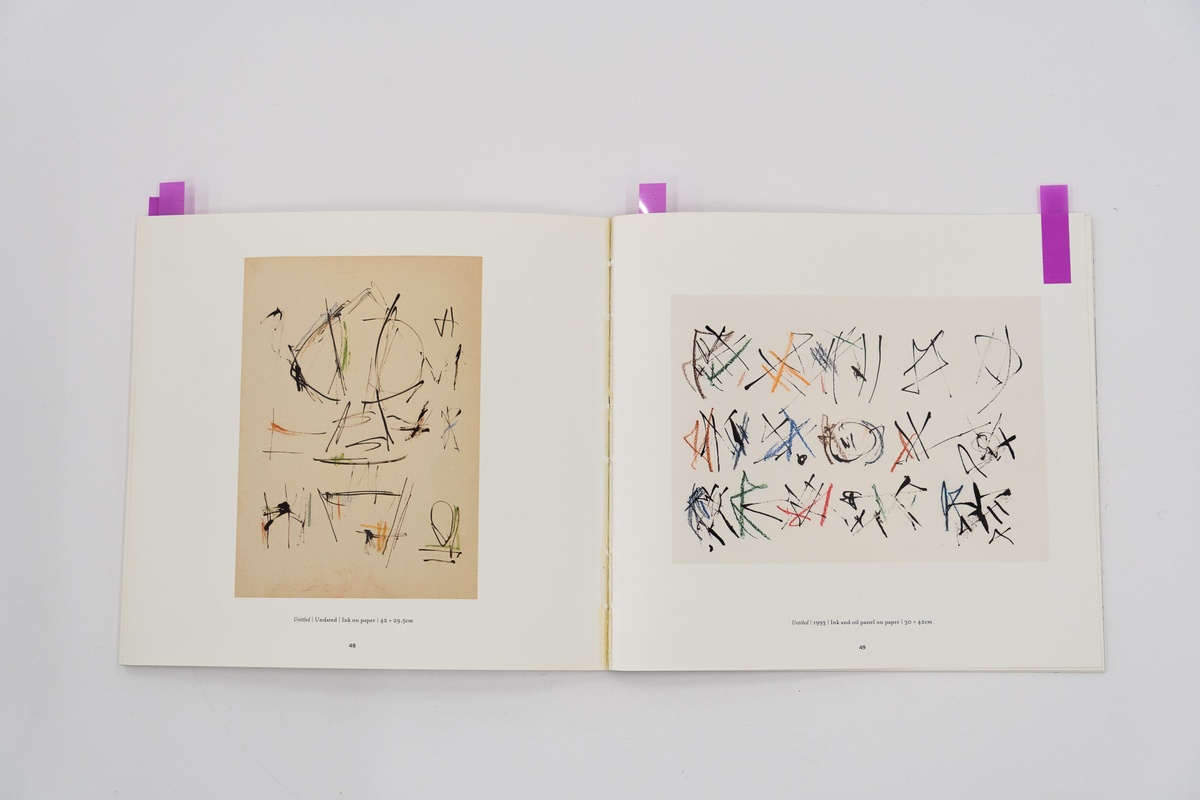

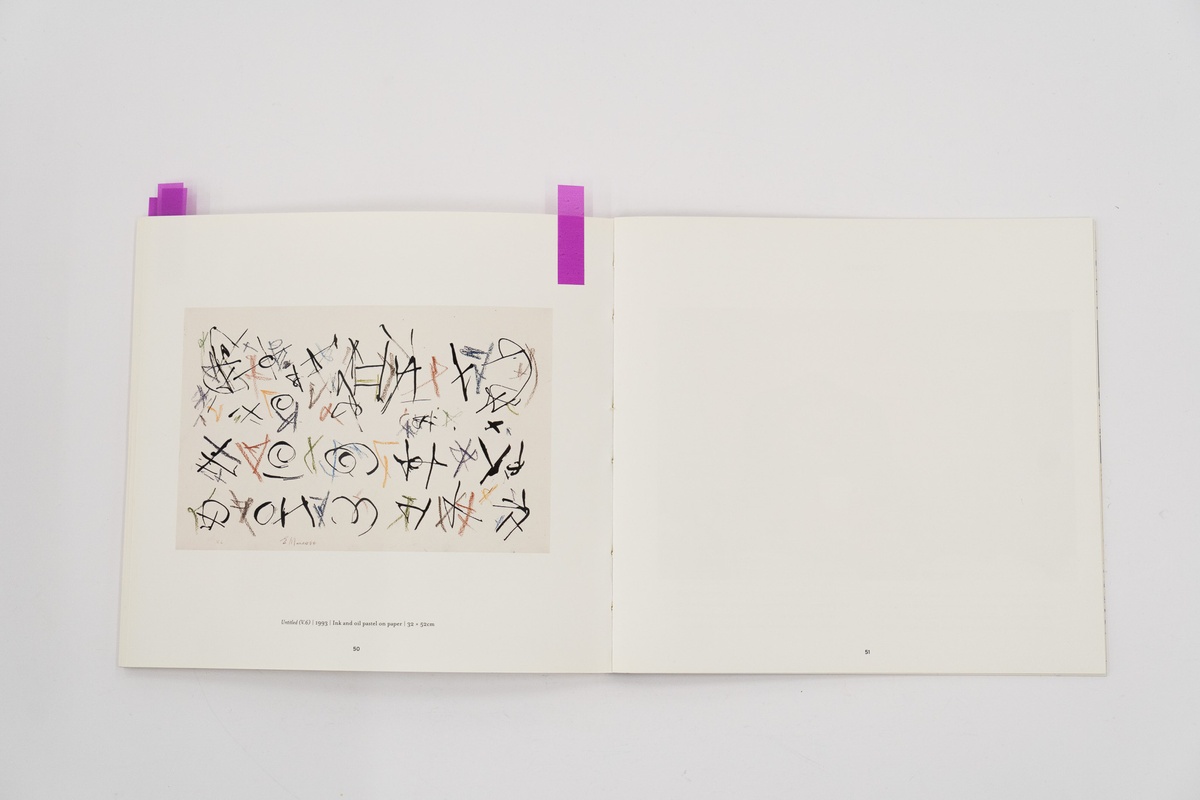

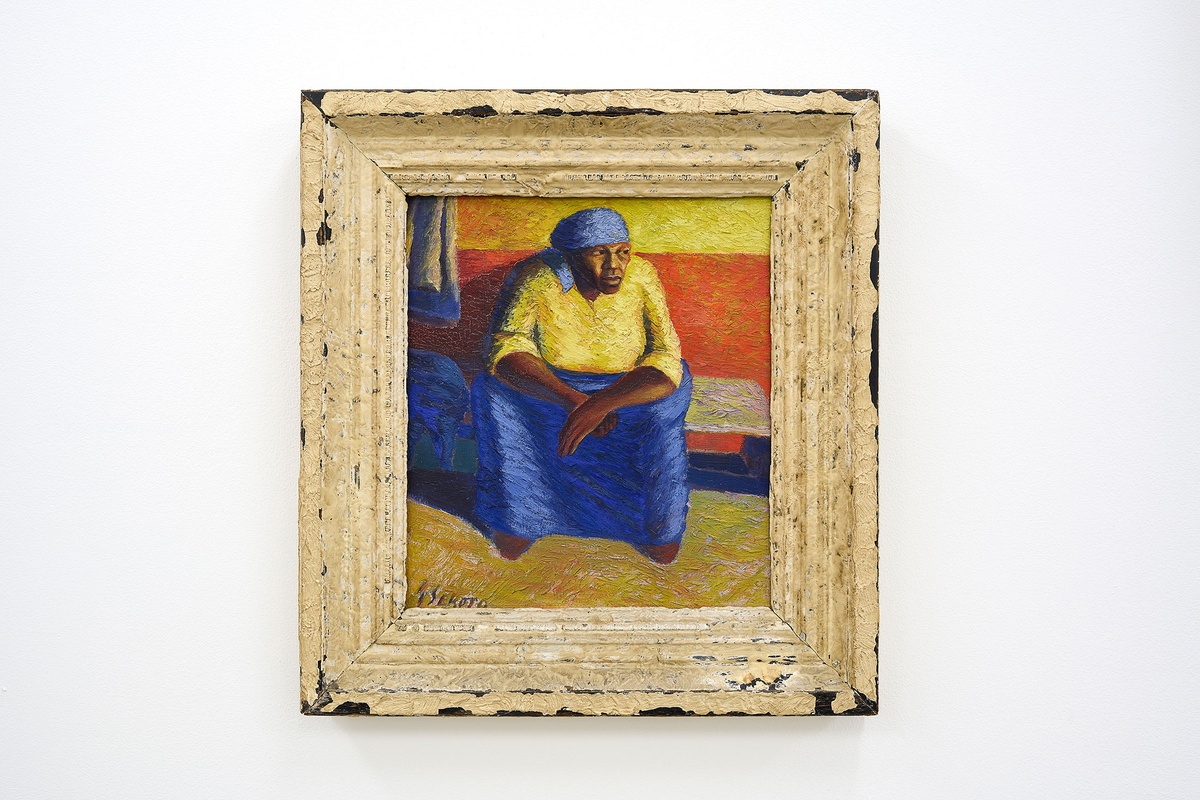

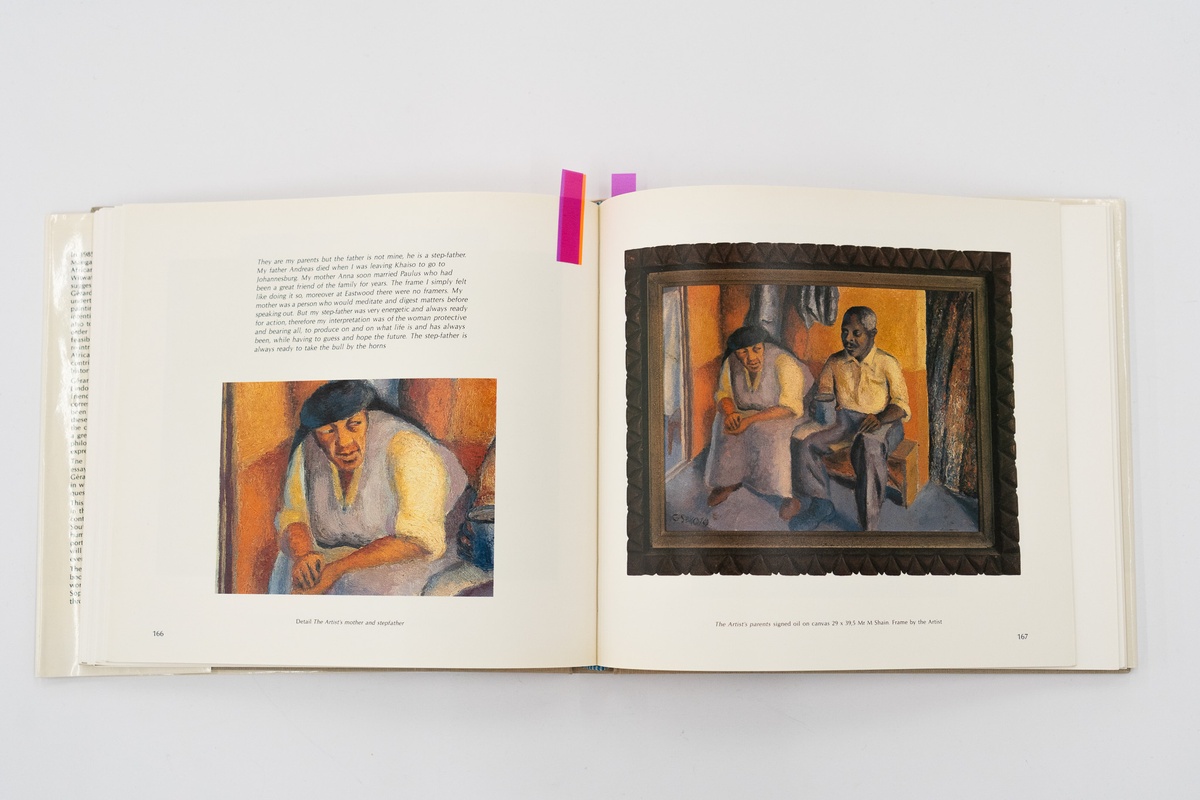

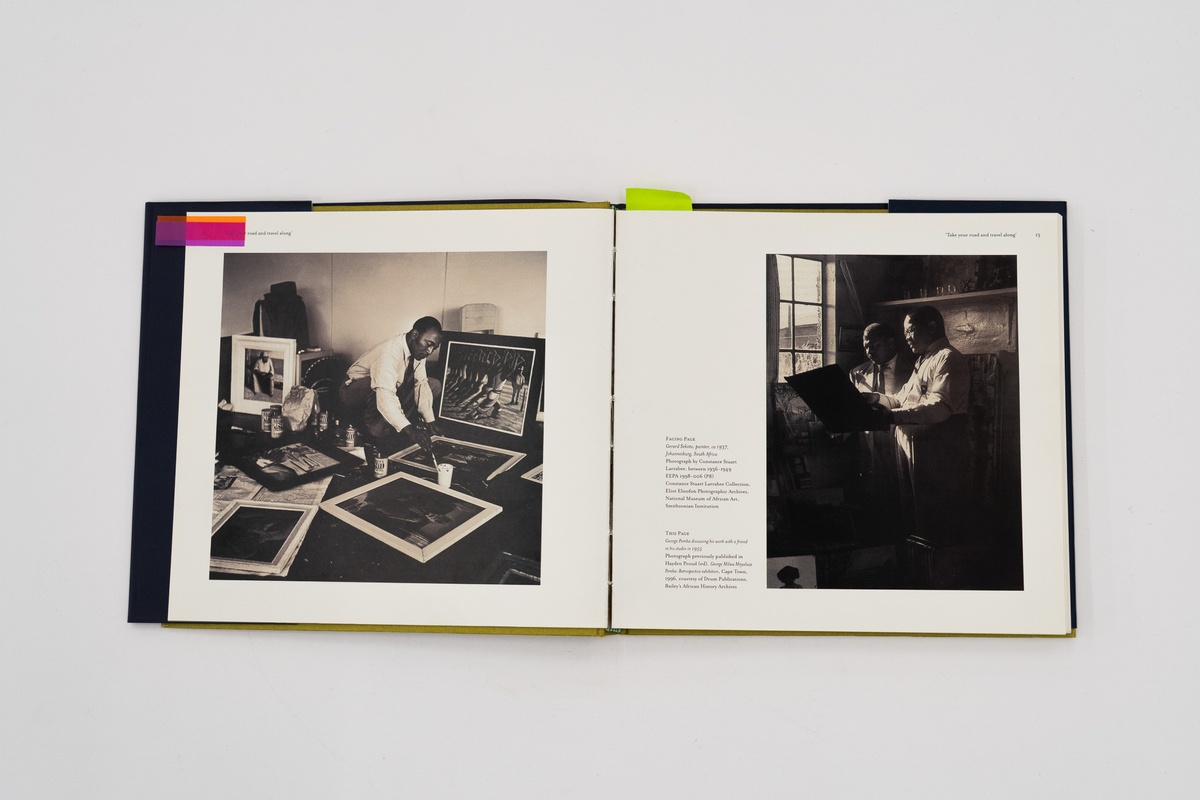

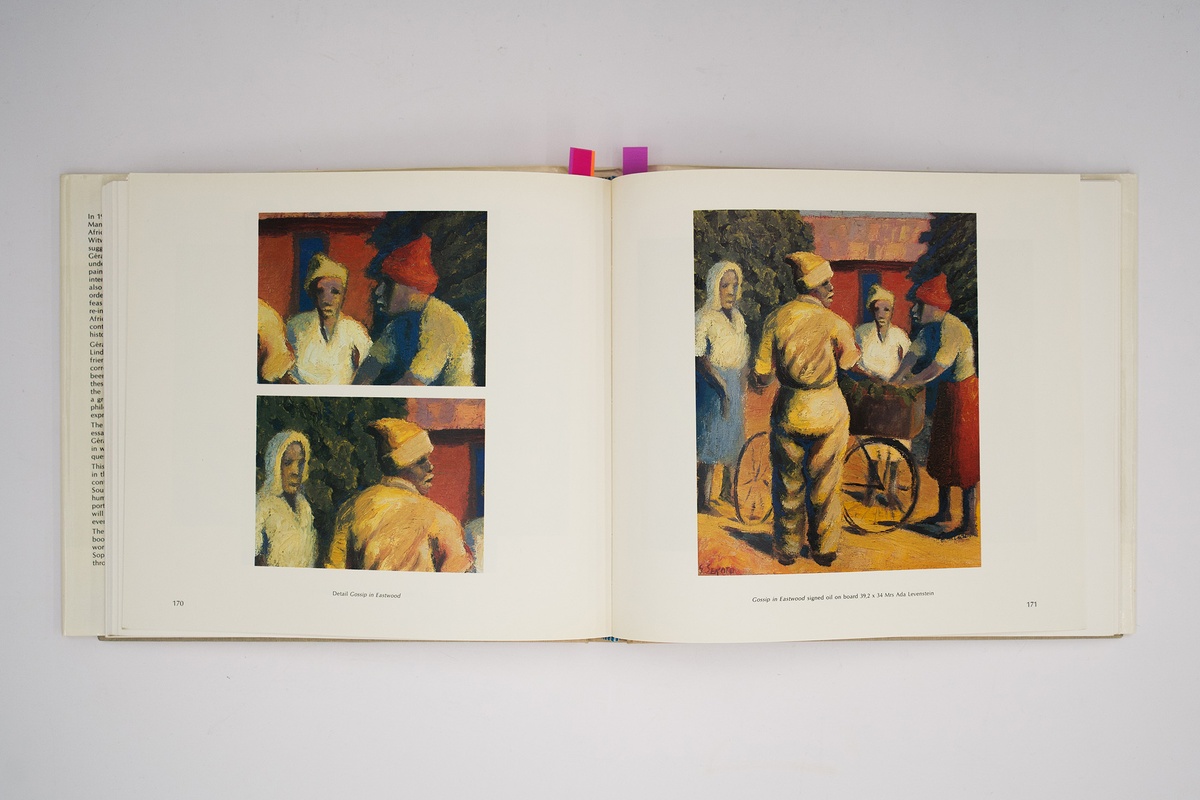

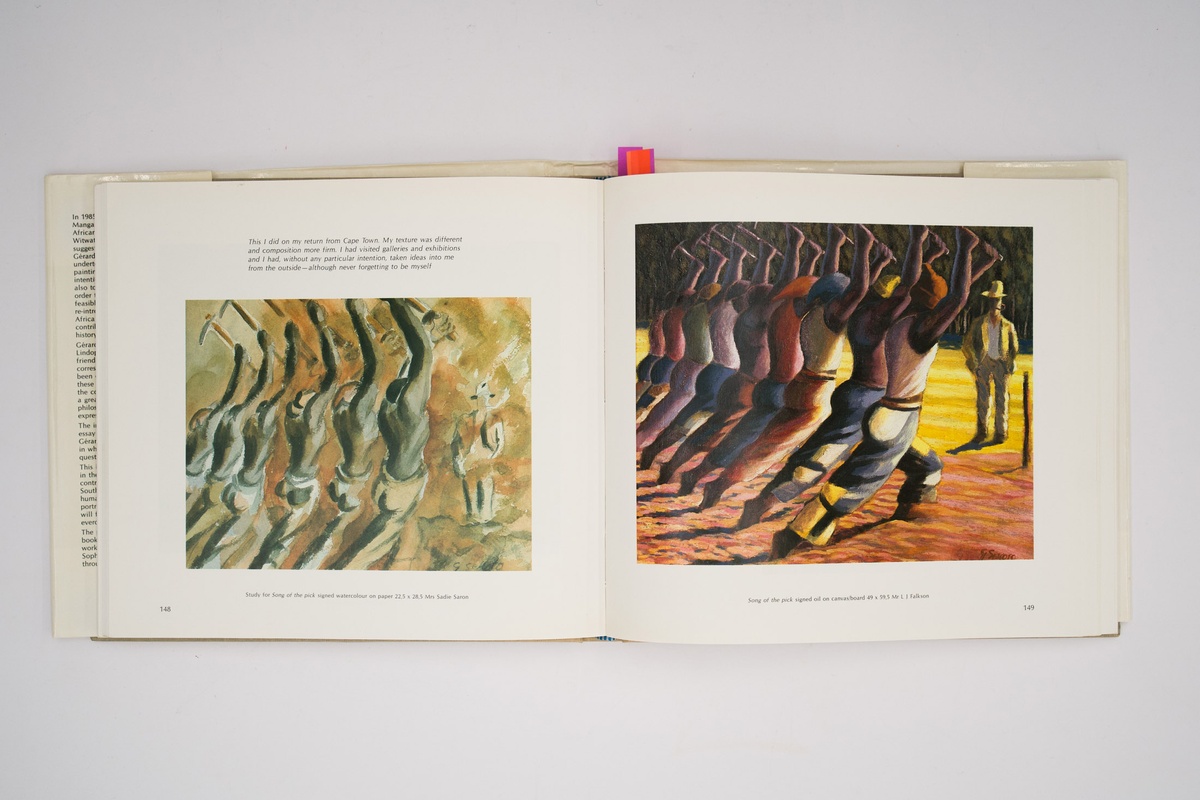

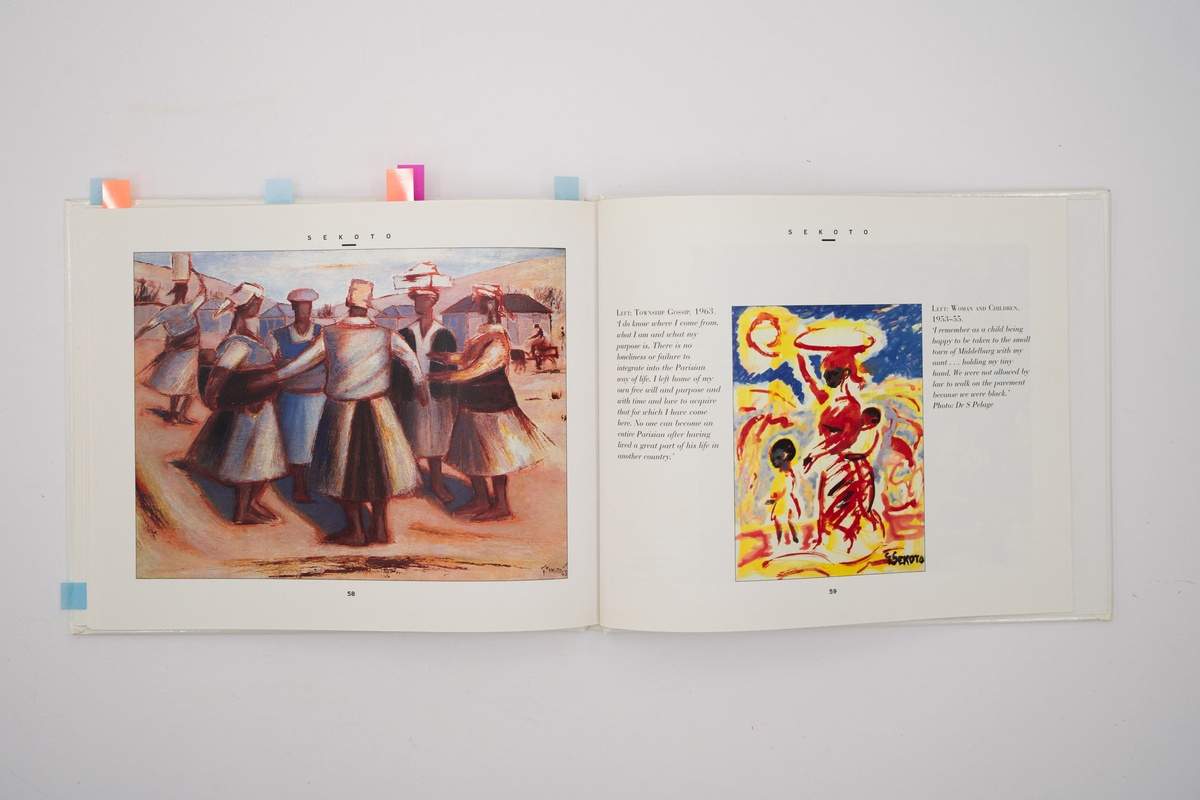

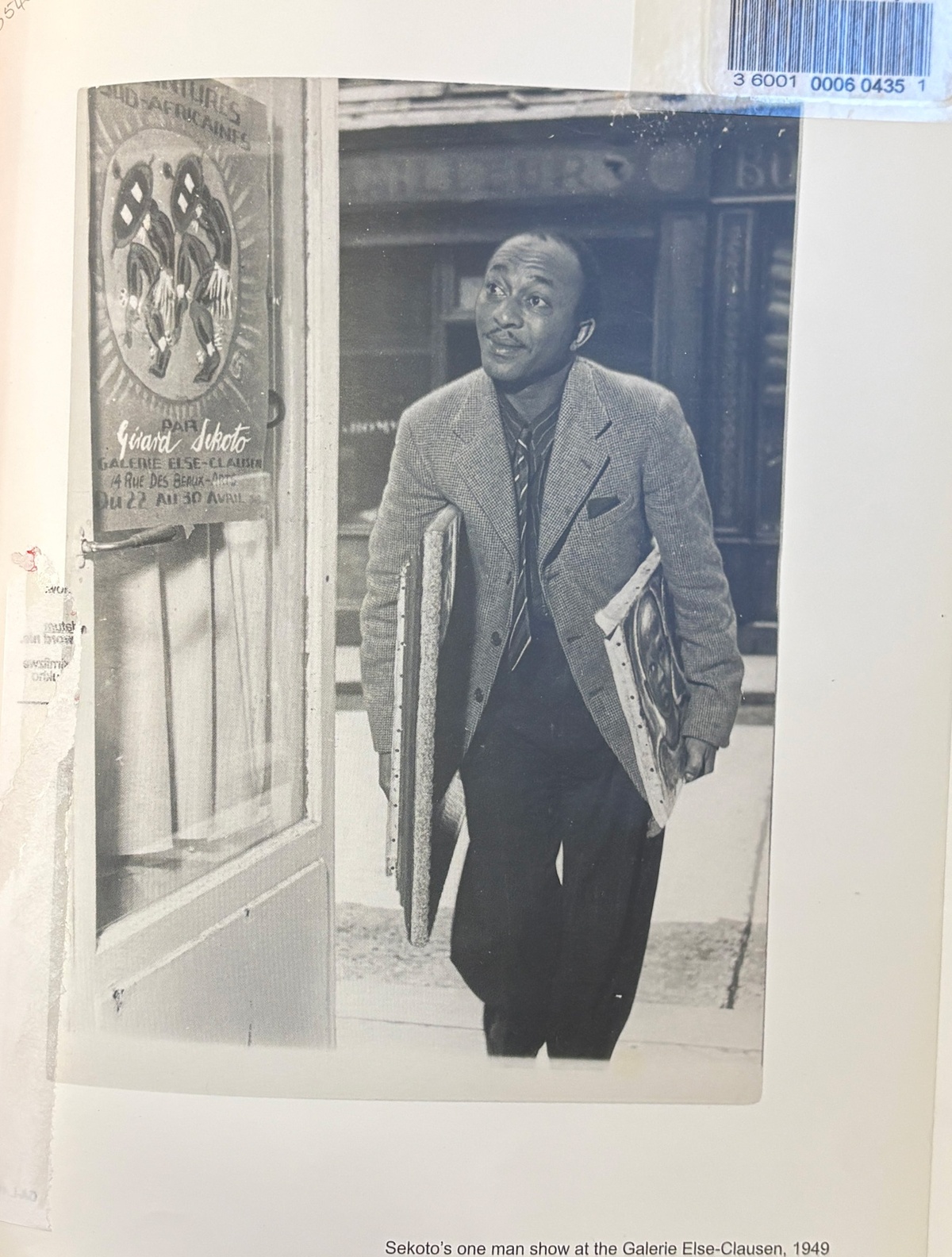

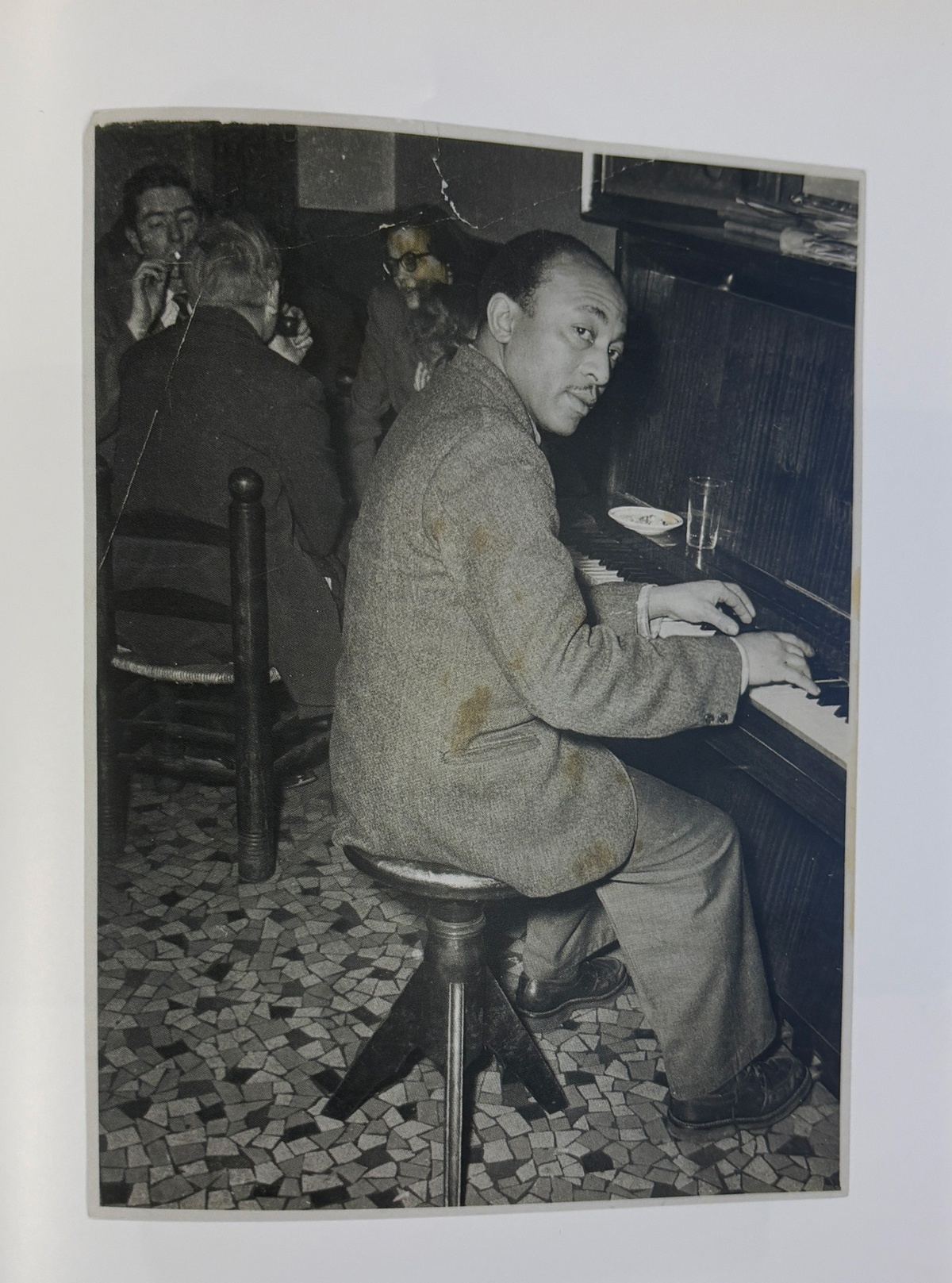

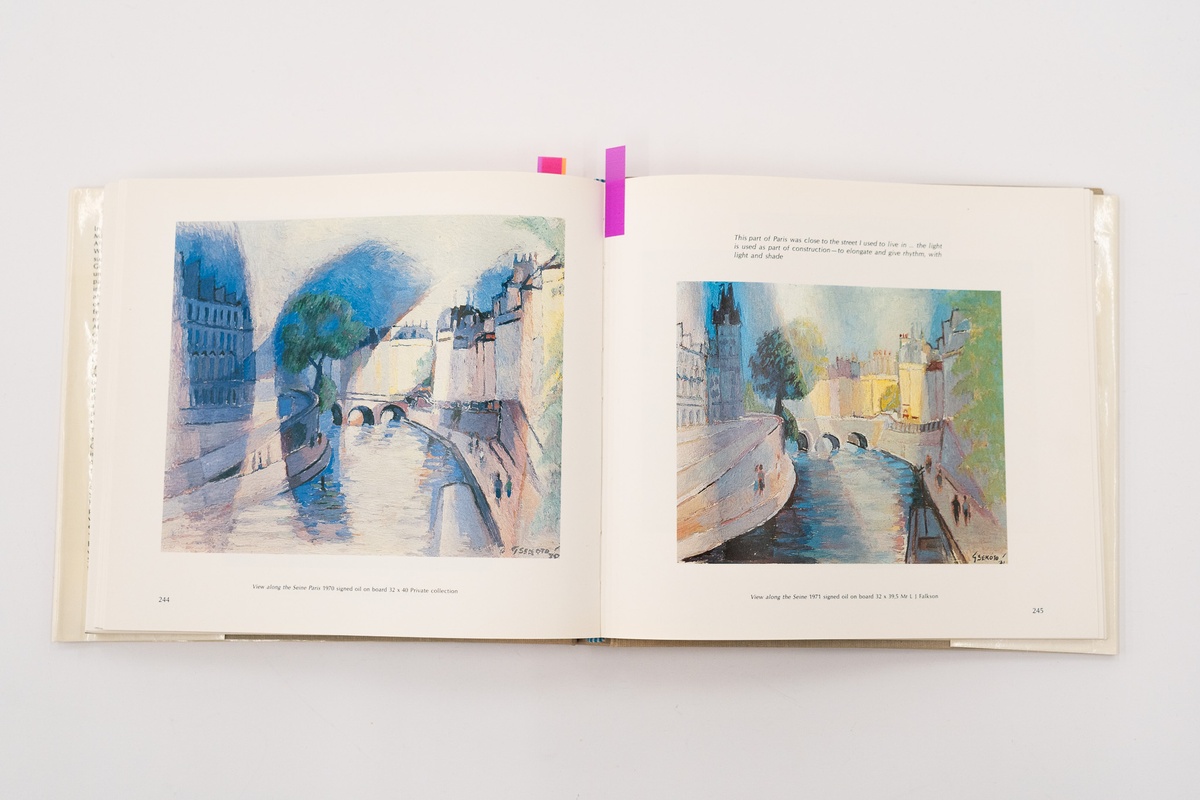

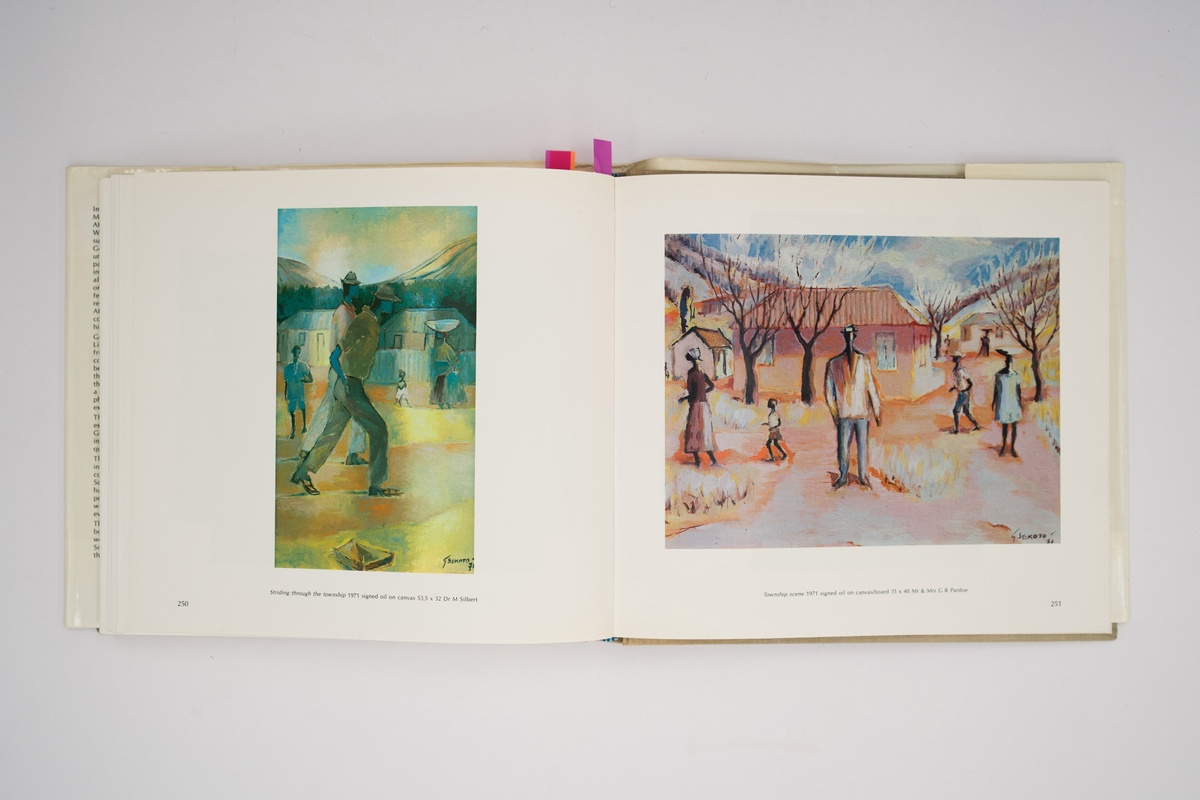

While visiting Sightlines in A4’s Gallery, artist Inga Somdyala was particularly drawn to two works, Gerard Sekoto’s Le Pont St. Michel (1959) and Ernest Mancoba’s Untitled (1971). These works are exhibited alongside each other as part of a thematic grouping titled ‘Equal in Paris’, reflecting upon the many artists who flocked to what was once the ‘centre of the art world’. Somdyala is interested in these pioneers of African Modernist painting for their contributions to art history, but also their long-distance relationship with South Africa’s shifting national identity.

Many of the artists, writers, and musicians who left the country during Apartheid – including Sekoto, Ernest Cole, Dumile Feni, Mongezi Faza, Johnny Dyani, and Nat Nakasa – did not live to see its end, the 1994 election. Matthew Blackman touched upon these histories of exile during his Library residency.

Mancoba, however, was able to return to his country of birth shortly after this first democratic election, on the occasion of his retrospective at the Johannesburg Art Gallery, curated by Elza Miles. This visit was documented by Bridget Thompson in a short film, Ernest Mancoba at Home (1995). At the film’s conclusion, Mancoba says of this triumphant moment, “This is beyond all my dreams, all my expectations, all my hopes. It is like a miracle.”

During his residency in the A4 Library, Somdyala aims to explore the dissonance held by the word ‘home’ for the arts practitioners who experienced exile, and the effects of their absence on the South African cultural landscape. Looking closely at a 1995 photograph of Mancoba taken in Cape Town at the Company’s Gardens, he writes,

Having struggled to establish himself as a human being – and an artist – in the years prior to the formal institution of Apartheid, how does this political ‘happy ending’ affect his experience of returning to his native country as a French citizen? I wonder if his eyes reveal relief or betray discomfort.

Somdyala has already spent many afternoons reading in the A4 Library and welcomed our invitation to respond to the archive as a resident. Though he is primarily an artist with a studio practice which includes painting, sculpture, and video, he researches and writes in parallel, “because it feels like an essential exercise in mapping the often long trajectory of ideas.”

–

The Library residency offers practitioners time and space to pursue their particular research queries and interests, working in and among our expansive collection of publications and miscellaneous printed matter. Residents have access to all our books and ephemera, the collaborative assistance of Daniel Malan in the role of librarian, and the support of the curatorial team over a two-week period. A4 is interested in sharing modes of research and investigation with our community, exploring ways of showing practitioners' process. We encourage residents to ‘think out loud’ via marginalia, recording their meanderings through books, essays, excerpts, and images, making the often opaque work of research visible. Towards the residency's end, practitioners are invited to develop a small programming component or engagement with the library's users and invited guests.

Reflections on belonging in dialogue with Bridget Thompson’s documentary film Ernest Mancoba at Home (1994), which follows the artist's brief return to South Africa in 1994 after almost six decades' absence. – October 1, 2025

While in residence in the Library, Inga Somdyala, together with Khanya Mashabela and Daniel Malan, wonders about South African arts practitioners who left the country during apartheid, and the effects of exile on their understanding of home, belonging, citizenship, and national identity. – September 17, 2025