J.G. We didn’t set out to make an exhibition about inheritances, thresholds, and grief. It began with a will to do something with you, Penny, inspired, in some part, by seeing Will again at the Michaelis School of Fine Art.

Almost immediately, you began inviting other voices into the conversation. One thing led to another – a work to another work, another relationship, and perspective.

We found ourselves, through an ongoing conversation, following along this improvisatory line.

When I think about Will as an artwork, and its relationship to thinking about inheritances, estates, and death, I immediately think of Colin [Richards] – this extraordinary creative partnership between you and Colin and the influence you have, and Colin continues to have, on the arts ecology here.

What underpins your individual practices is this tremendous collaboration. This is epitomised in your approach, attuned to the relational quality between all things.

The title of the exhibition only emerged very much later, as the title of Colin’s work, A Little After This.

P.S. It’s a beautiful title and keeps becoming relevant in so many ways. As we continued our conversation, once we had the title in hand, we figured, ok, well, what is This? Well, This, demonstrative in language, is something you point to. In the event that the thing is not physically present, this can be a way to introduce narrative. What is a Little After? Everything that is after, is also now, and now also marks before, and before points to the future.

This, this title, the way it emerged, speaks to the continuation of its emergence.

J.G. Let’s walk the line of the exhibition. As we arrive on the landing, we are immediately drawn to Kathryn Smith’s scans of this skull.

P.S. We may, at first, think of it as appearing in black and white, as being monochromatic. Rather, it’s blue-ish, encircled in the line.

J.G. The tempo is slow, invites a patient and considered looking as the rendering of the skull revolves. The depth of field is curious.

P.S. You see the inside and the outside simultaneously. You lose the sense of boundary by seeing through it.

J.G. The skull then speaks to Yoko Ono’s Sky T.V. that was first conceived of in 1966. Framed in the circle, and circling around, the skull looks towards the sky that is framed in this small, square TV. The monitor draws a boundary on what we see as infinite, radiating out.

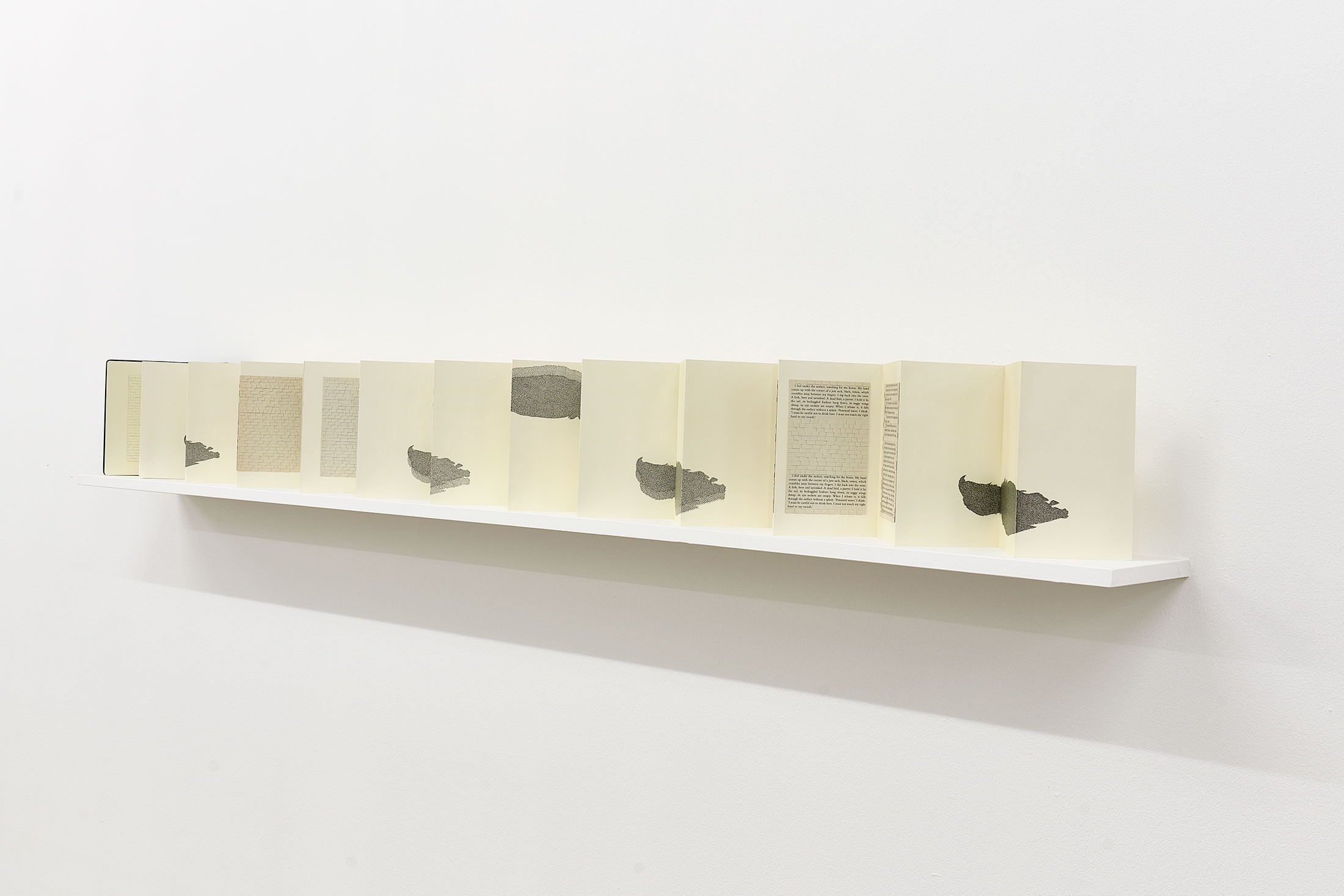

P.S. Arriving at Colin Richards’ concertina line. The hand is very present in this one, and the horizontal axis of the folded-out pages prompts you to walk along the line of the work.

J.G. That’s interesting, as there is almost no evidence of the hand in either the skull, or the sky works. You said something the other day that is quintessential of Colin’s practice: you spoke about the cross-hatchings that Colin favoured in his drawings, his focus on making these small, deliberate lines: how he knew that the line was relevant, that lines aren’t only about what falls on one side or another of the line, but that the line takes up space – line is a thing, is a this. Since then, we have realised that the themes the artworks can speak to in this exhibition, when collected together like this, can all be looked at through the apparatus of the line. Line, in other words, can be used as a tool for engaging the themes of this exhibition; line as a link, as the place between states, as a point of transition, or as a continuum.

P.S. Colin articulated it precisely, theoretically and philosophically – as line being a hinge between the visual and the linguistic. Line connects both sides.

In scientific illustration (Colin was a medical illustrator, and this led him into the arts) all aspects of the line should have capacity to be ‘objectively’ calibrated. They’re interrelated, as in art, but art takes on subjectivity. Colin took on the critical problem of illustration in this context, feeding it back into questions around, specifically, the linguistic and the visual, the space between image and text, challenging modernist art values where illustration had been given a negative cast in pursuit of disciplinary purity. At that time, illustration was denigrated in the fine arts. He was able to extrapolate a huge critical and creative space in his exploration of the line as hinge. And I think this idea of the line is a key part of this exhibition.

This mosaic effect of the blank paper in the work is made from the margins of a copy of Crusoe’s Treasure Island, the parts that didn’t contain words and print. He also performed this action with the words. He cut out and assembled these into this Moleskine concertina book. The scale of each blank mosaic paper piece mirrors the cut out words – is reminiscent of the scale of a word. These are an absence that is not an absence, it is the book, the words in the book, and not the words in the book. It’s the material of the book, in which we would read, but also see the words and the spaces between the words and around the words. A word can be a shape, and it can be the shape of its absence.

The line that is created between cuts is evident by the appearance of a shadowed edge. This effect of being able to see a line is created by the smallest relief of the paper on the page coupled with the ambient light that is cast.

J.G. It is both a sculpture and an archive in a book.

P.S. Again, we keep thinking about these as monochrome but there is colour. The colour of the page is off-white, like the colour of the back of the canvas – you see it when you look towards the paintings hanging in the gallery – the reverse of the paintings in line.

J.G. Let’s use this as an opportunity to move forwards towards Will. There is an obvious line in the Will project, which is your life. Well, at least there is the clear line of your life as living and then as not living, at least in this world. As you’re speaking now, I was imagining each object like a cross-hatched little touch that collectively represents a life.

How did Will become? Did it begin from a first object?

P.S. I think Will began when I started to work with installation, which in turn emerged from my work with painting. In the painting Melancholia, I had a taxidermied monkey as reference.

Increasingly, I started thinking about the thing itself, the object as its physical self and what it is referencing, at the same time.

There was always this tension between the actuality and the reference. I made an installation, Reconnaissance 1900-1997, the same year as I started Will, which transformed into a massive corpus of found objects, Charmed Lives. From this corpus I selected individual ‘characters’ that then entered Will… Even now, I still have a complicated relationship between materiality and reference. I think it’s a positive one, but anyway, that’s an aside.

‘Melancholia monkey’ hung around my studio and home, because I was disallowed from giving it back to what was then the Transvaal Museum from where it had been loaned. “It’s broken at the seams, it’s no good anymore, we don’t want it in the museum, you can have it,” they said. You’re presented with it and wonder, What am I doing now, presented with this object back to me? An object which I have to look after, or don’t look after, or throw away, or about which people think, “You’re weird, why have you got this monkey hanging around your place?” It raised questions beyond the creature’s symbolism.

The monkey wasn’t the first object. It was a bit of the monkey’s skin that had fallen off its owner. It has since been lost. Skin is an important boundary line, human skin in particular. Especially when you’re more than one, when you’re one with another. Touching. And the boundary is porous and it suffers. It’s young, it’s old. It’s a psychic and social reality.

J.G. That the piece of monkey skin was the first object, and represents the line, is beautiful.

P.S. I think so too. It evokes the complexity of skin, especially in its shed form. From birth we shed skin. Then, getting to the point of death (which I don’t see as obviously scary or negative – even in the face of grief, a shattering of self, there is transformation) involves thinking about what it is to be truly cold as felt through the skin. The cold skin is one bit of evidence that the person is no longer in the form that they were before. You touch that person through your skin. There are two skins needed to feel this; theirs, and yours.

J.G. And where you touch, is something.

P.S. Yes, the line is relational. You are never only one thing or the other.

J.G. Standing here, one is made aware that each of the objects is also its colours, its textures, and its shape. All these shapes are of different scale. There is an interplay throughout the exhibition between scale and size, from Colin’s line, the smallest line, to the towering crates, and the back of this canvas line, which feels monumental in scale.

P.S. Monumental, but not industrial in scale. My body is its reference.

J.G. We have been finding, as a team, that we have different opinions of where to turn next. After the Will wall, I turn right, walking through the crates and along the back of the canvas line to find the Sithole sculpture carved from a single branch of wood. It almost feels like it might be meant to be packed away into one of these crates somehow, like it’s a part of this Will project. The work is very much a line in form. It’s also a link, it is a branch of a tree and it is the evidence of the hand that carved it.

Then one enters the widest part from which to view Portia Zvavahera’s painting, and to walk along the line of Maitland paintings.

P.S. It is interesting to consider the direction because, should one be inclined to go left instead… well, left is the page being read in English, left to right, or the way we drive here, on the left-hand side of the road. Perhaps it’s a choice visitors can make, which route to take through the exhibition.

J.G. The wayfinder document, when assembled, does bind the works in an order. The order in which they will appear in the book will take people from Will, and turn right. Visitors should try out these different routes through the exhibition, whether to enter from the wide end, or take the narrow tunnel through your paintings towards Portia Zvavahera’s painting Embraced and Protected in You.

P.S. The painting is remarkable, there is this very definite use of line in parts and, at the same time, Portia’s shape-making process lets the line continue and bleed across the surface and edge into the boundaries of the figures.

Having Portia’s painting facing the Maitland works enables a conversation between the mark-making in these paintings. In Portia’s painting, the mark is made through the pressure of her hand painting then applying the stamp-print on the canvas. As I work, marks emerge through the painting medium itself. The ink and glue pools and leaves its residue when dry, which creates a variety of circles. Onto this surface, the application of oil impasto makes these individual marks that, when seen together, cohere into a swarm. There are parallels here in the way Portia applies the print, the block, to her painted surface.

In the usual way of describing artworks, paintings are described in terms of ‘colour’ and drawing in terms of ‘line’, but the painting is also line, and the drawing is also colour.

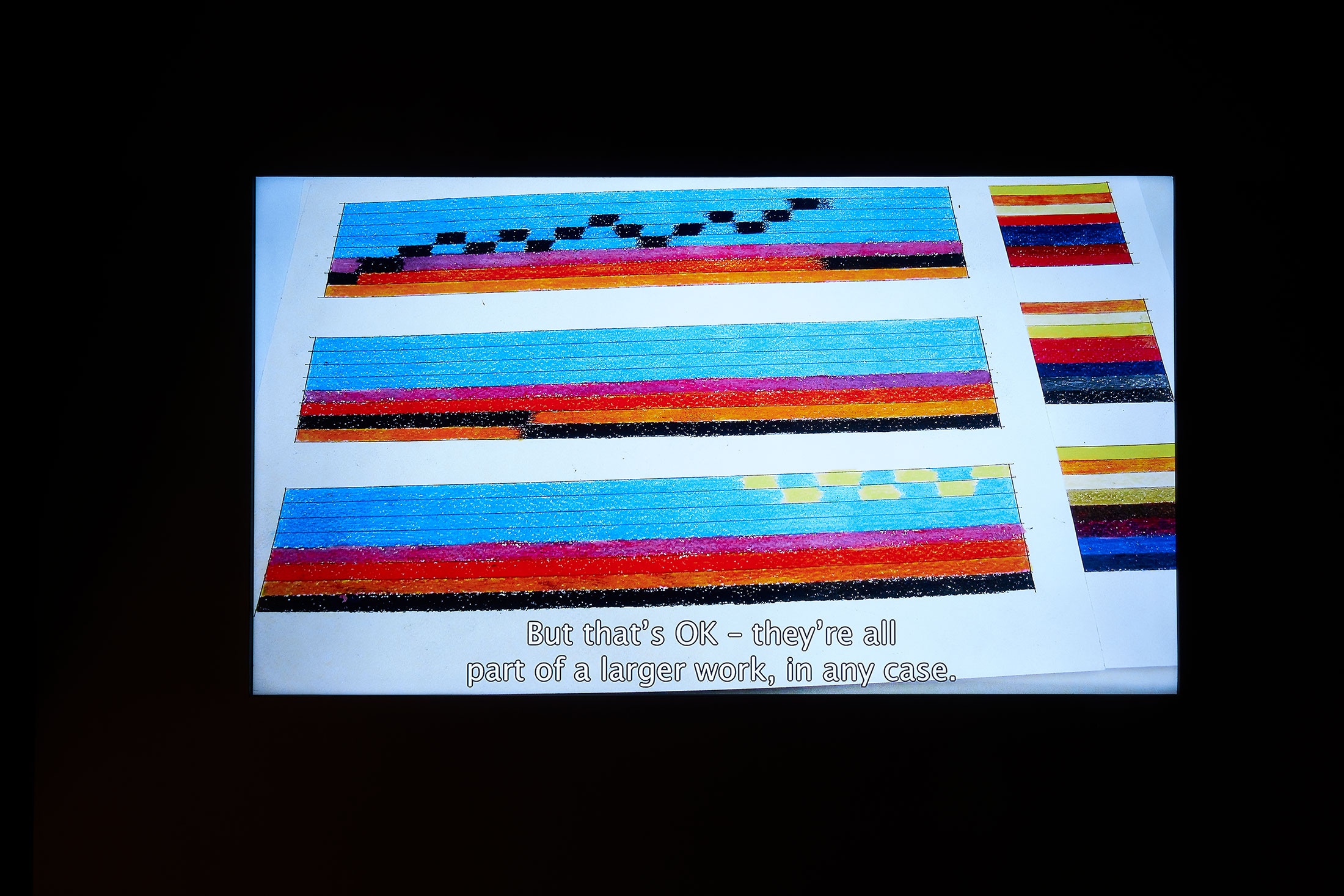

J.G. Saying, now we reach Alex Da Corte’s work while on this walkabout isn’t quite accurate, as the sound of ROY G BIV bleeds throughout the environment. We’ve encountered the sound all along.

P.S. It’s the audible line that travels through the exhibition and coheres an ephemeral boundary. There’s a scene in the film where you see Alex’s feet, he’s tiptoeing as if along a line and carrying that boombox indicating how important sound is to this experience.

J.G. Early on in the conversations towards this project we understood that inheritances are a central theme in the exhibition. ROY G BIV and Alex’s embodiment of these art ancestors links to this theme – a homage to Duchamp, Brancusi, Baldessari and Johns, and also to the intertextuality, borrowing, and iteration that is central to all artmaking.

We then find Gerard Sekoto’s small painting of Paris. It feels quite solitary, placed here. The painting, from 1959, talks to the blue of Kathryn’s skull, of Yoko’s sky.

P.S. The feeling of blue-ish.

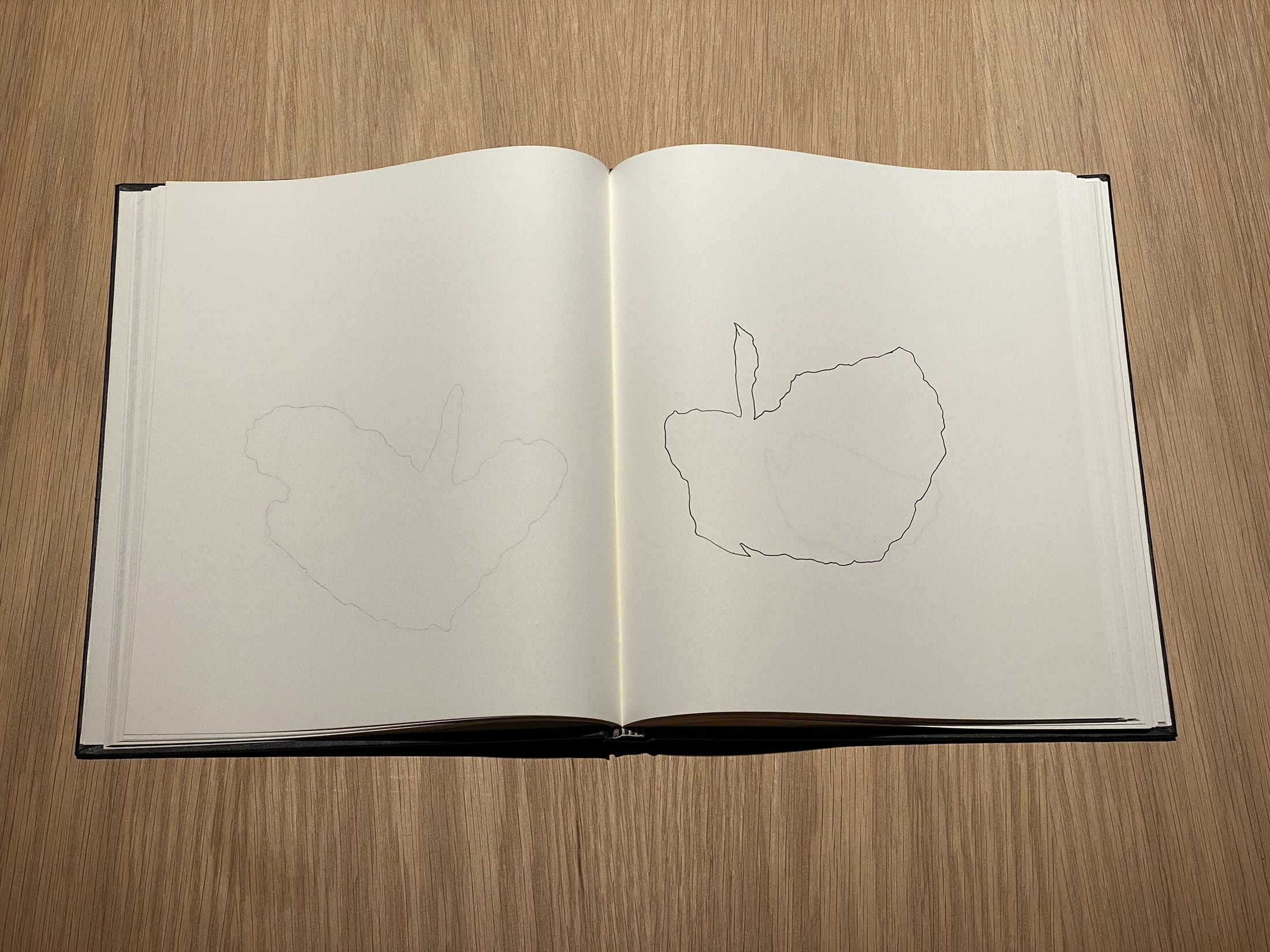

J.G. When I returned home from Frieze London where I had seen Shilpa Gupta’s 100 Hand-drawn Maps (those were of England) and I spoke to you about the work – it was so impactful, in that whole massive arena of things, it was the work that stayed with me – you immediately said that, yes, it would work in the exhibition, the work being concerned with edges and boundaries, those real and imagined.

P.S. Shilpa’s work also brings in this other element, that of the air. As the fan creates wind, the movement of the air becomes material as the pages are blown over.

Our other senses engage, seeing, and feeling the wind, hearing the sound.

J.G. The title of Moshekwa Langa’s The Morning After! reads like an accompaniment to the exhibition title, of Colin’s work A Little After This – like another version of it, even.

P.S. Colour tends to hover and become most potent on the margins, creating a visual field from different combinations of colour application. Then, he draws a very lyrical line onto this field, a line that has the feeling of having been drawn as a continuous gesture.

J.G. In Shilpa Gupta’s 100 Hand-drawn Maps of South Africa, we asked participants who drew their versions of South Africa to draw with one continuous line, or as close to one line as they can, which is the artist’s specification. Obviously, Lesotho is in the way of making this wholly possible.

When I saw Ane Hjort Guttu’s work Untitled (The City at Night) the A4 team were in the process of measuring and photographing each Will object, creating a digital inventory that would respond to a physical archive. But what the physical archive would look like was still a question. In this work, we come across the physical archive – these beautifully kept drawers, belonging to an anonymous artist who makes her work with no intention of it being shown. The work is made for the archive, for its storage, so to speak. We were invested in this research question at A4 at the time, of sustainable practices in the arts and as part of this, in the maintenance and reuse of things. And we were wanting to find a storage solution for Will that could also be its installation strategy, which we have accomplished here in the exhibition.

I’m wondering, looking at Will now, as ordered, cohered, organised into this archive, what do you think? How does seeing it this way make you feel?

P.S. That’s an interesting question, because my ‘natural’ aesthetic is not really to separate things. I mean, it’s almost as if it’s now a contradiction, which I’m happy about. It shows, even dramatises, the discernment that motivates the choices of the Will objects, of which to include, marking the particularity of each. With the organisation you’ve brought to the corpus, it draws a line that contains, but a line that does not end (at least for the moment), because I’ll keep adding bits to the distributed body that is Will, until the day that the things are dispersed.

Then, each object starts a new life, connecting with other bodies.

We’re doing this all the time in life, we are connecting all the time, and this particular way of working with Will materialises that connection.

The crates, some of which are displayed open, allows each thing to settle for a while in a habitat made specifically for it. I love that these crates have been made with precision, craft and care. In organising, we’ve put things together, but we’ve also split them... It’s this question of a line again, in one form or another. For the moment, this is where we draw the line on the project. A provisional line. One that speaks to A Little After This.

J.G. Perhaps this is a good place to end this part of the conversation. In Ane Hjort Guttu’s film, the unnamed artist/protagonist talks about creating these small artworks that fit the scale of the domestic space in which she worked, at home at the table. You mentioned Colin working with the smallest nib size that he could find.

P.S. He used the tiniest nib that he could source, point 0000 whatever. And he also worked at the table at home.

J.G. It’s the thinnest material capacity, but it fully occupies space…