K.M. I thought it would be good to start by talking through the research process and how you began this project of thinking through these photographs and ideas.

M.B. The 2022 republication of Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage, and the inclusion of the last chapter, ‘Black Ingenuity’, set me on this journey. When the book was first published in 1967, I think Cole decided that the chapter should remain untitled, but ultimately, it was taken out entirely.

Editing an essay by Jacob Dlamini for an upcoming book project was another thing that sparked my interest. He was writing about how the lens through which we’ve looked at apartheid has prioritised politics and not addressed the culture of the time.

Despite being under severe oppression and living in poverty, people were leading fulfilling lives and had developed a very interesting and under-researched culture.

D.M. Cole’s photos were smuggled out of the country, and the book was published in America. Apparently, the publishers weren't interested in that last chapter because they were focused on creating a strong anti-apartheid message, and images of 'black joy' didn’t necessarily fit.

M.B. I think that’s exactly right. The photographs selected by the American publishers for the first edition are photojournalism, a documentation of the oppression that was happening in South Africa. That was a valid outlook on the country at the time, but what has been lost is the culture that developed. It's strange in a way, because obviously Miriam Makeba was in America at the same time and was very famous, but nobody seemed to have made the connection that these two things went hand in hand.

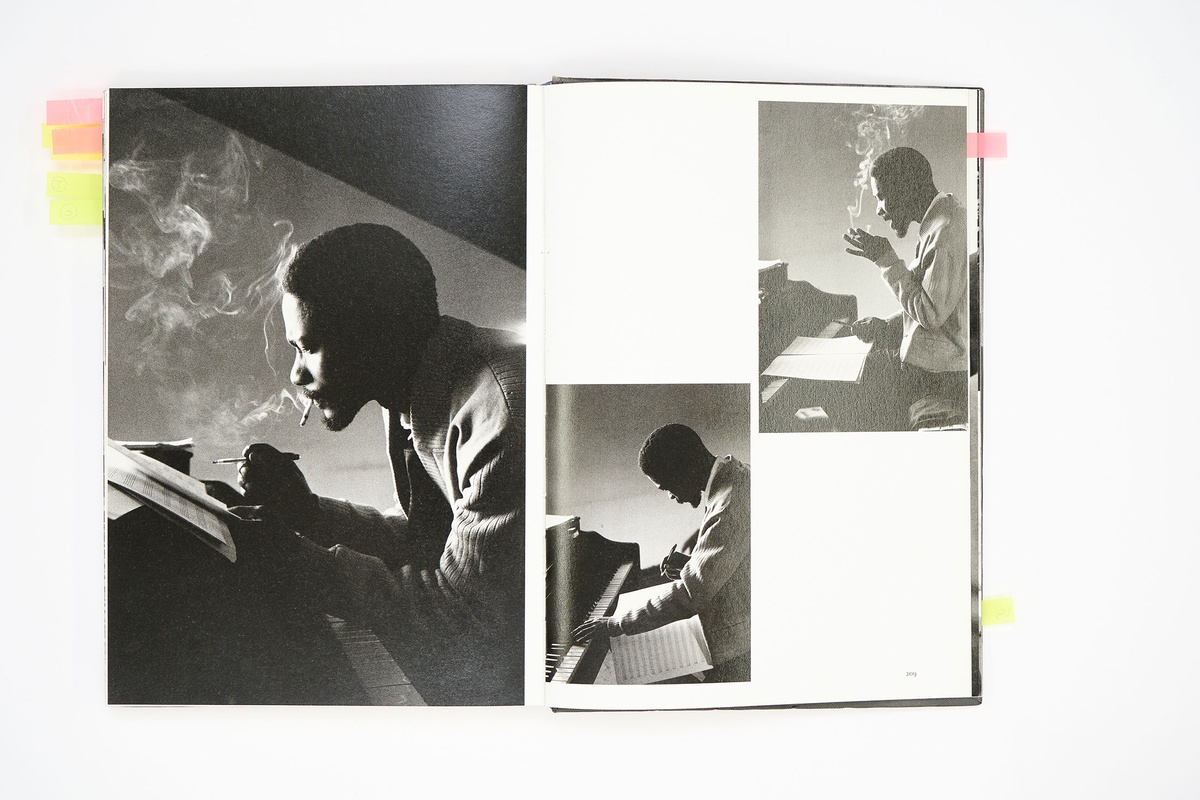

What is surprising about the chapter is that despite the imagery, there isn't a great deal of information on the people photographed. The first image, which was – to me – instantly recognisable, is of Gideon Nxumalo, who majorly contributed to the orchestration of King Kong and some other musicals, and produced two very famous jazz albums [Jazz Fantasia (1962) and Gideon Plays (1968)]. But in the essay leading up to it, they just say something like, "pianist/composer at piano". This is an important figure – why aren't we identifying these people and identifying the culture that surrounded them, that they created? Nxumalo's first album was recorded at Wits Hall around the time of the Rivonia Trials, after the Sharpeville massacre. During one of the songs, he slips in a riff from Nkosi Sikilel' iAfrika. He is signalling "this is political". Many of these works are political in some sense.

D.M. In terms of images, are there sources besides Drum Magazine that we're missing in A4’s library?

M.B. There's this other magazine running concurrently called Zonk!. They actually got into making films and made the film African Jim (colloqually Jim comes to Jo'burg) in 1949. That archive only exists in the National Library, as far as I can tell, and the National Library is currently closed. Ernest Cole began his career in photojournalism at Zonk!.

K.M. On the subject of journalism and documentary photography, what were the conditions in which these images were taken, and why were the details lost? I was looking at the documents from the Wits archives on Ernest Cole, and you could see the notes that he wrote as he was taking the pictures, but they were quite sparse.

As this process has unfolded at A4, it feels like you're trying to gather and write an entire cultural history made out of fragments. There have been moments where it has been quite frustrating. How are you feeling about how the past weeks and months of research have gone? Do you feel like you have open avenues to walk down to get the information you're looking for?

M.B. It is very frustrating. In part, it has to do with apartheid. This whole cultural movement was tied in with the [African National] Congress movement, which was deeply inclusive.

It was a multi-racial, multi-ethnic movement that was happening. Apartheid went out to absolutely crush it.

As a result, a huge amount was lost. Many of these people went into exile – many of them died young while in exile – and with them their recollections. The impetus to the movement was deeply broken and as a result, there is very little information out there other than Drum Magazine. There are aspects of this archive, but they're under-utilised.

The other element to this, and this might seem a little flippant, is that the art world has generally been the custodian of this information, and it more often works on a 300-word premise: "We need 300 words for this artwork because we're going to put it on auction and that's all we need." Depth is lost in that world. But there are obviously people like Elza Miles out there. And someone like Steven Sack, who did go out and document some of this. But the transition of information from that generation to the next is lacking.

K.M. This reminds me of the conversation we've had about Selby Mvusi and the idea that because so few of those works went on sale via auction has meant that they weren’t written into the story, which feels important to note.

M.B. Selby Mvusi was an incredibly interesting person and a thinker. He wrote a lot, and yet he's almost entirely forgotten, beyond Elza Miles book [Selby Mvusi: to fly with the north bird south (2015)].

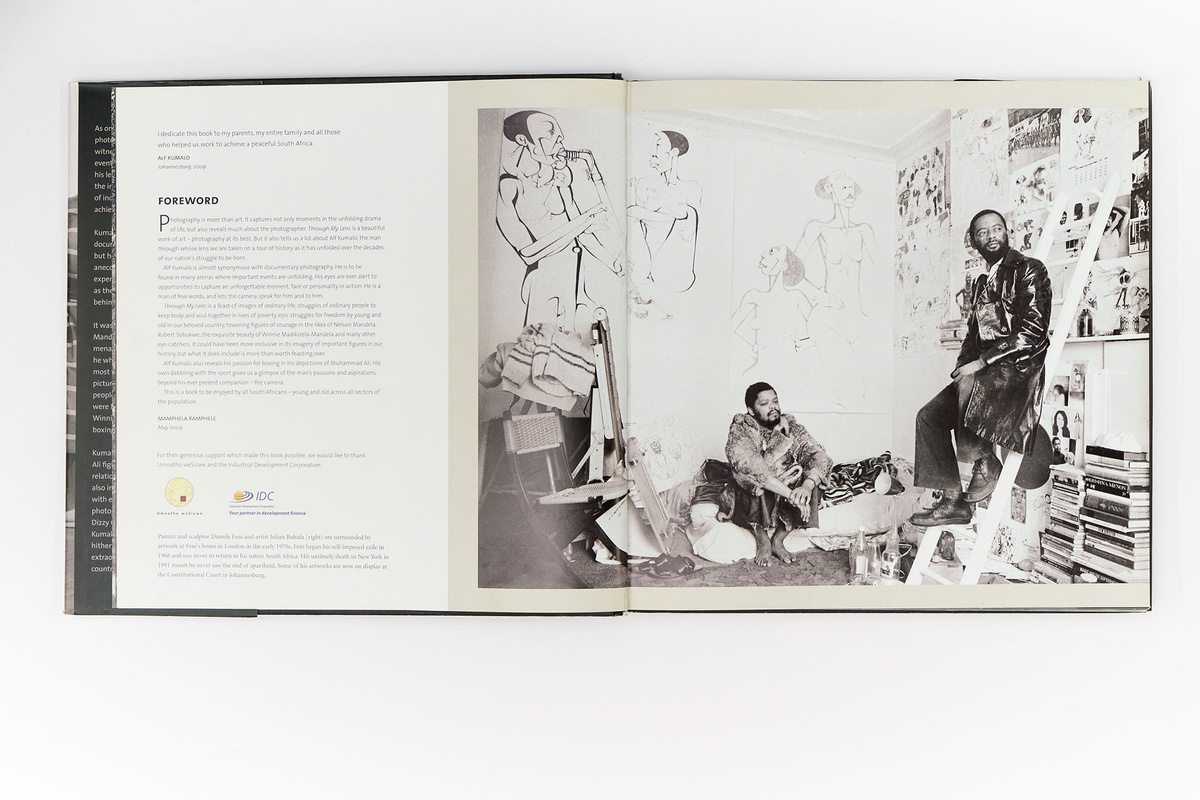

K.M. The varied experiences of exile have been fascinating. You were able to match Cole’s image of the drummer to the photograph by Alf Kumalo in Dumile Feni’s studio, identifying the musician as Julian Bahula. While researching Bahula, I came across his Africa Sounds concert at Alexandra Palace and the 100 Club, where he was collaborating with people like Fela Kuti and Miriam Makheba in London, and it seems like it was the most beautiful time. But then you look at Ernest Cole and Nat Nakasa in America, and it’s much darker.

M.B. Talking about that, there's another man whose identity I was able to figure out from Peter Magubane's book Soweto (1977). It was interesting to me because I saw an image by Cole at the same festival. The man in Magubane’s photo is Mongezi Feza, who also went into exile and later died of untreated pneumonia in England at the age of thirty. Going back to the Kumalo photograph of Dumile Feni and Julian Bahula, their experiences of exile seem quite different. I think Dumile really struggled but Julian, by the sounds of it, thrived. I think he was more politically active than most of the others, and he connected with that political activist community. Talking about music and exile, I didn't realise before this research process that Sekoto spent much of his time in Paris as a jazz singer.

Maybe music allows for an easier transition.

When you are creating images and writing about a place, it is quite alien for Europeans and Americans to understand what it is to be in South Africa. Ideas around apartheid are understood, but they're also untranslatable. They are very specific to place and time.

K.M. It’s also a reminder that writing (and maybe photography, though not as intensely) is, at its core, a solitary pursuit. When you're making music, you're in a band, making things happen with other people. You're constantly connecting to a sense of community.

D.M. Are there more photos relating to this time from the Kumalo and Cole archives? I know they found all those Cole photos in Sweden, but those are mostly from America.

M.B. There is definitely more to it because in the London exhibition of Cole's photography, there is a photograph of Philip Tabane and Julian Bahula, which I had only seen a crop of as an album cover. So yes, there are other photographs around. The thing is, in South Africa, it's always about gaining access to these archives.

D.M. I loved this moment in your research when you saw the image of the African drums in House of Bondage and then showed it to me on the album cover. I think that you've done it a number of times, where you play this game of making connections through different sources. Do you plan to keep that game going, and to work it into the writing?

M.B. I do want to keep the game going because you learn so much by finding people and objects in the background.

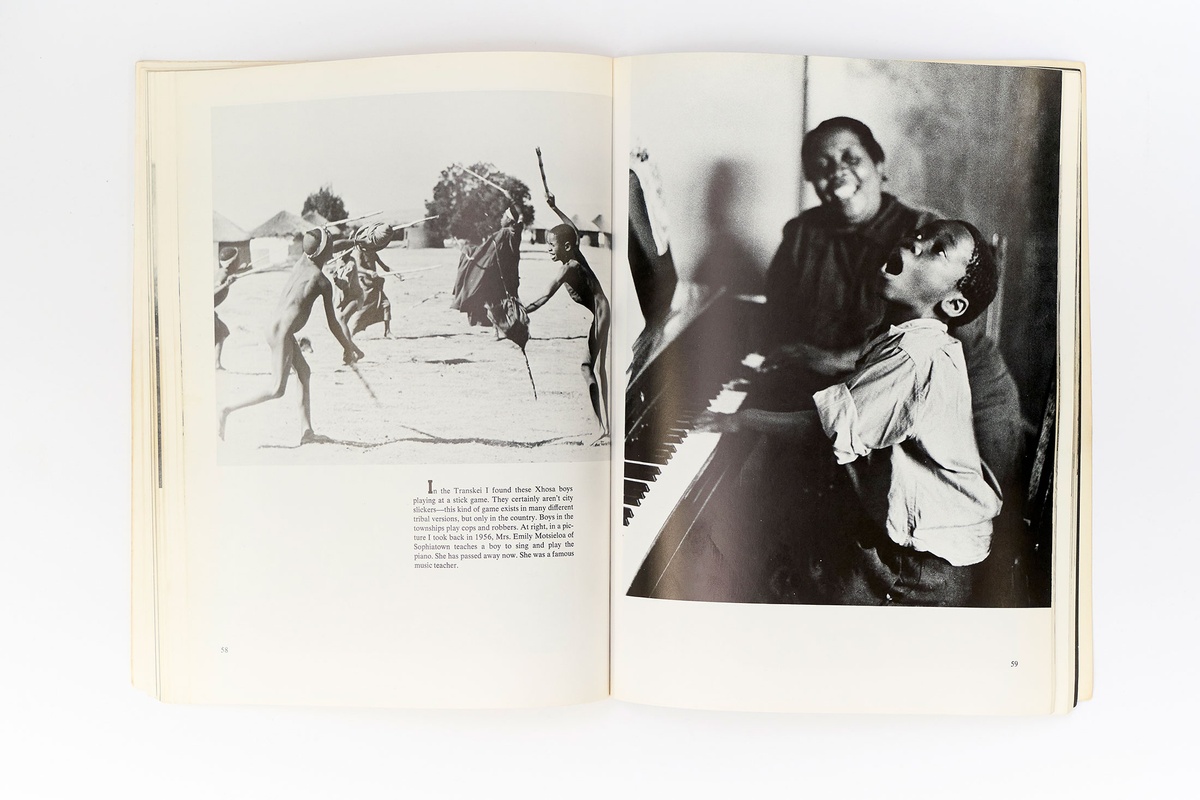

There's a famous Peter Magubane photograph of a child singing and playing the piano with his piano teacher sitting behind him. The piano teacher turns out to be a very important – Emily Motsieloa – woman who was in the Merry Blackbirds and who composed a lot of the early South African jazz music of the 1930s and '40s. She's just sitting in the background, slightly out of focus, and everybody's concentrating on this cute little boy with his mouth open. It's a very appealing image, but there's a bigger story behind it. Most people just focus on the little boy, but who is that woman sitting in the background?

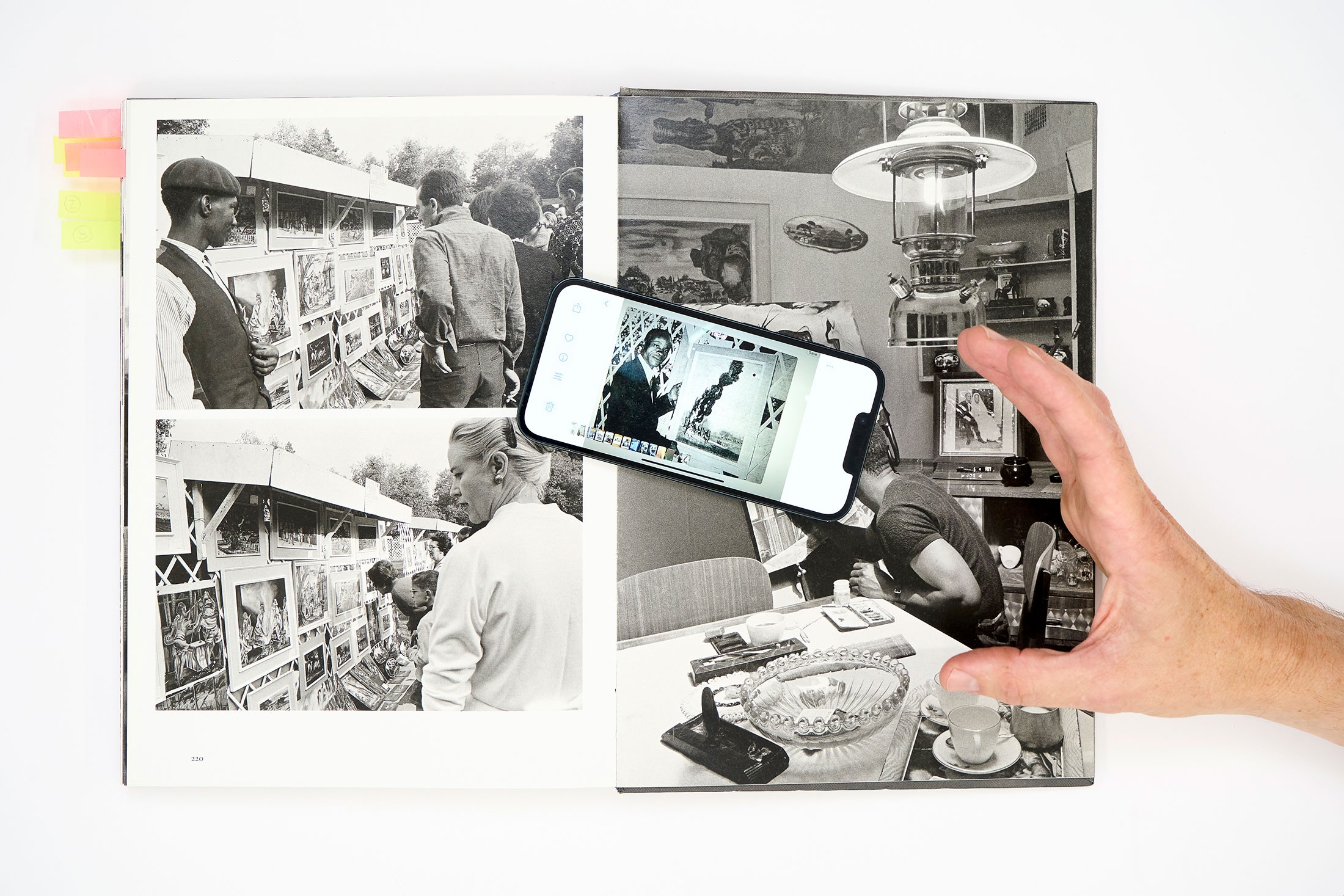

I would love to have a little book of these connections. I've only explored a couple of these images because you can spend an entire day looking at some weird little detail in the background. For example, I was looking at the fence in these two Cole photographs and thinking, “Is this John Mohl's Artists Under the Sun?” If you read about John Mohl, there's a famous story about how he showed in the Johannesburg Art Gallery and then, as apartheid took over, he was thrown out of exhibiting there. So in 1960, he began organising these Artists Under the Sun exhibitions where artists would show their works on the fences of Joubert Park, outside the museum.

The only photograph of John Mohl that I know of is this photograph of him in Joubert Park, and then I realised that the fence matches the Cole images. It's not absolutely certain that this is Artists Under the Sun, but it seems likely.

K.M. I read that they later moved to Zoo Lake in Parktown, Johannesburg. This reminds me of the conversation we had about the idea of spatialising these photographs. Even if you're familiar with where some of these photographs were taken, you might not understand where these places are in relation to each other. With Artists Under the Sun, it’s sometimes spoken about as an attempt to “bring art to the people”. That doesn’t seem like a strong explanation because a lot of black people wouldn't have been able to move freely in these parts of Johannesburg. It seems more likely that it was about getting access to a buying audience to enable black artists to make money from their art.

We’ve spoken about Gladys Mgudlandlu and John Mohl not really existing in the same circles as the Drum Magazine people, perhaps because most of his paintings were more romantic. Looking at these photos of Artists Under the Sun, the paintings have an ‘African Romanticism’ energy about them. There was a sense that the only way to earn money and autonomy through art as a black person during this period was to appeal to white audiences.

M.B. That is exactly what Tim Couzens – who is the only person I know to have interviewed Mohl – writes about what Mohl says in the 1960s. His market is the white community, those are the people who buy art. He said he always struggled to explain to the people who lived around him why his art had value. The idea of the value of painting existed for him around the Johannesburg Art Museum. It's a short interview, but Mohl is clearly interested in this idea. His idea of beauty also seems shaped by his experiences of rural South Africa, and moving around Botswana and Namibia. Drum is interested in beauty but in a very different way. Mohl was mission school-educated, like many of the people at Drum, but he's of a slightly older generation of artists. Like Sekoto, who had left South Africa by that stage. It's that older generation, sitting back and observing, wondering if it's all just modernity and money and gangsters.

The stories of urbanisation and modernity are fundamentally joined to one another.

There was a new urban culture developing alongside continuous references to inherited culture. My interest at the moment is understanding how that happened, and how odd it looks in comparison to other modernities.