Hayden Malan (H.M.) and Cynthia Fan (C.F.) are Pear_ed. Lemeeze Davids (L.D.) alphabetises fragments from an interview to catalogue their practice.

Hayden Malan (H.M.) and Cynthia Fan (C.F.) are Pear_ed. Lemeeze Davids (L.D.) alphabetises fragments from an interview to catalogue their practice.

A. Artist

H.M. I studied art, but I didn't much enjoy making art. It was nice to have Pear_ed as a space where I could feel like I wasn’t a ‘Capital A’ artist – a space where you're just making ‘stuff’, not isolated.

B. Beginning

C.F. I loved biology in school though it was never taught from a plant’s perspective. When I thought of studying molecular biology, it was in the context of studying toward a career in cancer research. Then a lecturer showed us a slide about the induction of tumours in baby mice – there was no way I was going to do that. My career path changed because of that one slide. In another lecture, we were shown a time-lapse of plants reviving themselves. Learning about these resurrection plants in South Africa is the first clear memory I have of knowing, “Wow. Plants are so cool.”

H.M. I have a childhood memory of planting an avocado seed, of digging the seed into the middle of the grass in the bedroom-sized garden. I didn’t tell anyone. Studying landscape architecture with a group of people who could tell you the Latin names of all these species really pushed me. We would go on walks where they would share great stories about each plant. I learned about plants through these shared anecdotes.

C. Collaboration

C.F. Historically, many Ikebana artists worked with sculptors, architects, and forgers. There was room for crediting multiple people. The idea of working alone has always been quite restrictive for me – not creative enough. You’re always losing out on ideas from other people.

H.M. At Hiddingh Library1 I would look for books of conversations. With Pear_ed, we’re having a bit of a dance with things that are alive and also make us feel more alive, but we’re all learning as we go along. Conversation is nice when you are allowed space to express your vulnerabilities safely, and you get pushed into another's circle of knowledge.

D. Document

C.F. I was going over my chats with Hayden from before Pear_ed existed. One of the things he said was, “It would be really fun to watch each other work one day.” That side, how someone works, is often left out of an exhibition. Pear_ed is not this finished thing; it’s happening while we're going about our normal lives. It’s for us to document and keep track of the process.

E. Emoji language

H.M. Barbara McClintock, an American cell biology scientist, expressed her research through specific jargon – a ‘plant language’ – that remains confined to the structure of the essay. For me, floristry speaks using a ‘plant language’ too, but instead of text, flowers and vegetation are pictorial symbols, functioning a bit like emojis.

C.F. Caribbean-American writer, Jamaica Kincaid describes her garden as another form of writing. She says that plants are waiting to be read in a language we don't yet understand.

F. Flowers

C.F. I became interested in having flowers for the house when I moved out of university residence. I was doing it unconsciously because my mom always used to buy some when I was a child. Then, I started making arrangements at the restaurant where I was working at the time, and started researching flowers.

H.M. My mother worked at the florist where Cynthia worked too. That was our first big connection.

G. Gathering / Google Maps

H.M. Gathering is my approach – to walk around and find something. We were brainstorming what plants were in season for Hypothesis 1 (2023). I called my mom to ask what plants she’d recommend, and she told me to look for a date palm. I walked loops around A4 Arts Foundation, using Google Maps, trying to find one.

H. Human

H.M. Seeds Sistas, two women who teach herbal medicine, question humans’ obsession with what a plant can do for them. I often worry about whether we fall into the trap of thinking: “What can we extract”, where instead, we could practice listening.

L.D. Cynthia spoke about plants waiting to be read, indicating a balance between being the human interpreter and what the plant might be saying.

I. Ikebana

[from @pear_ed]

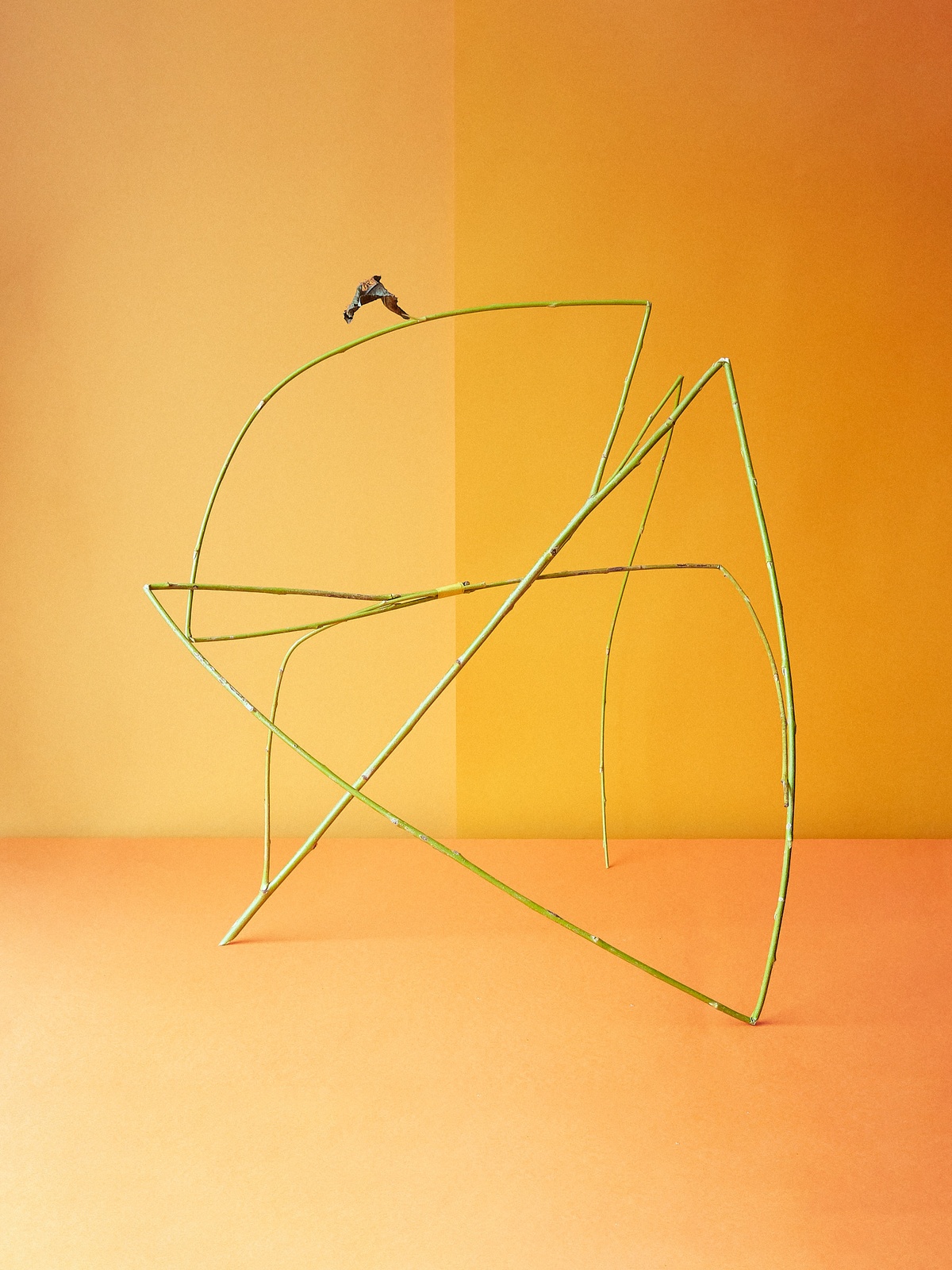

C.F. One of my favourite arrangements in the Ohara Ikebana School curriculum is the hanamai. When it was first taught to me in 2017, I understood that it was an arrangement that captured a conversation or an interaction between plants … ‘Hanamai’ actually translates to ‘flowers dancing’ – I like to think of it as an exchange.

J. Jargon

L.D. Both of your projects that you made at A4 borrow from scientific jargon, being called Hypothesis 1 & 2 and Evidence2.

H.M. I think we became slightly obsessed with the importance of the structure being scientific. For the future, I think we would like to do something that breaks with that impulse. In Bessie Head’s novel When Rain Clouds Gather, ‘book knowledge' becomes synonymous with jargon when European agricultural strategies fail to address local farming challenges. Unexpectedly, millet began to thrive between the fences instead. There’s a necessity to adapt to natural complexities outside of ‘book knowledge’.

K. Kosen Ohtsubo

H.M. Cynthia and I started our friendship over a Japanese ikebana artist, Kosen Ohtsubo. He pushed many boundaries, like taking photos of himself in a bath full of flowers as an ‘arrangement.’

L. Lessons

[from @pear_ed]

H.M. There is a multifaceted coldness that settles in during European winters… Things fall off, seem sparse. Both branches and bones tighten all over. I find the stagnation hard to deal with. And at the same time, it feels like a lesson. A lesson from plants to us – that the plants and ourselves are allowed to go dormant.

M. Metaphor

C.F. Maybe people are just looking for metaphors to use to speak about interconnectedness. In the tomato family, if one plant is eaten by an insect, it releases a chemical into the air. The plants that are near detect it and produce another chemical that makes their leaves taste bad.

L.D. South African British artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg talked about how, if you leave plants to their own devices, there is almost warfare between them.

C.F. Jamaica Kincaid noted that people often say, ‘Nature is like Prozac’, but this idea of nature having a soothing power is disturbing. If you work with plants, you’re watching something die or one thing taking over something else. It made me realise that you can't leave the world out of the garden.

N. Nasturtium

C.F. Wikipedia seems to have updated nasturtium’s etymology since I last read it. It used to be: Linnaeus, who chose the genus name because the plant reminded him of an ancient custom: After victory in battle, Romans erected a trophy pole on which the vanquished foe's armour and weapons were hung. The plant's round leaves reminded Linnaeus of shields and its flowers of blood-stained helmets. But Wikipedia now reads: The current genus name Tropaeolum, coined by Linnaeus, means 'little trophy’. Boring!3

O. Omens

[from @pear_ed]

H.M. A quote about Nandina domestica, by Tarna Klitzner of TKLA [a landscape architecture studio based in Cape Town]: “You’ve heard the story, right? Have I told you? You plant it outside your front door. On your way out in the morning, you tell it your bad dreams and it removes the ill, the bad omens. I can’t find the reference online. But I read that somewhere and I love it, so I believe it.”4

P. Primrose in the Salad

C.F. I heard that the common primrose can be used in salad, and I know it has a specific taste, so I put it to the test. If you're using the primrose in a salad, you're doing science.

L.D. Do you think trying to keep the flowers intact is what makes it art?

C.F. No. I think that's what places it exactly in the middle of the art-science pendulum. Because for me, I'm putting research into practice through an experiment.

Q. Question

What do plants really want?

R. Rigidity

[from @pear_ed]

H.M. We start to set up our guidelines [for Pear_ed]; a post every two weeks seems consistent and builds trust, a six-week gap and we start to worry about one another … These posts are meant to be easy. If the structure becomes too rigid, then we will be in the business of control, predictability, and maintenance. Probably Cynthia and I should not worry if the land we sit on gets washed away – I’m sure we will both learn to swim.

S. Spending more time with plants

L.D. There’s a phrase that emerges often: “Spending more time with plants.” It seems to be the core of Pear_ed – this idea of serendipity, sentimentality, rediscovery of the world. I was curious how spending more time with plants has changed the way that you deal with them.

H.M. Thinking about plants having a ‘language’, I realised that learning Dutch feels like a similar process. You hear these random words again and again, and eventually, they make sense in a certain context.

C.F. Barbara McClintock conducted hardcore genetics research on maize, but personally looked after the corn plants from which she was getting her samples. She was quoted saying, “I don’t feel I really know the story if I don’t watch the plant all the way along. So I know every plant in the field. I know them intimately. And I find it a great pleasure to know them.” I liked that approach.

T. Thoughts

[from @pear_ed]

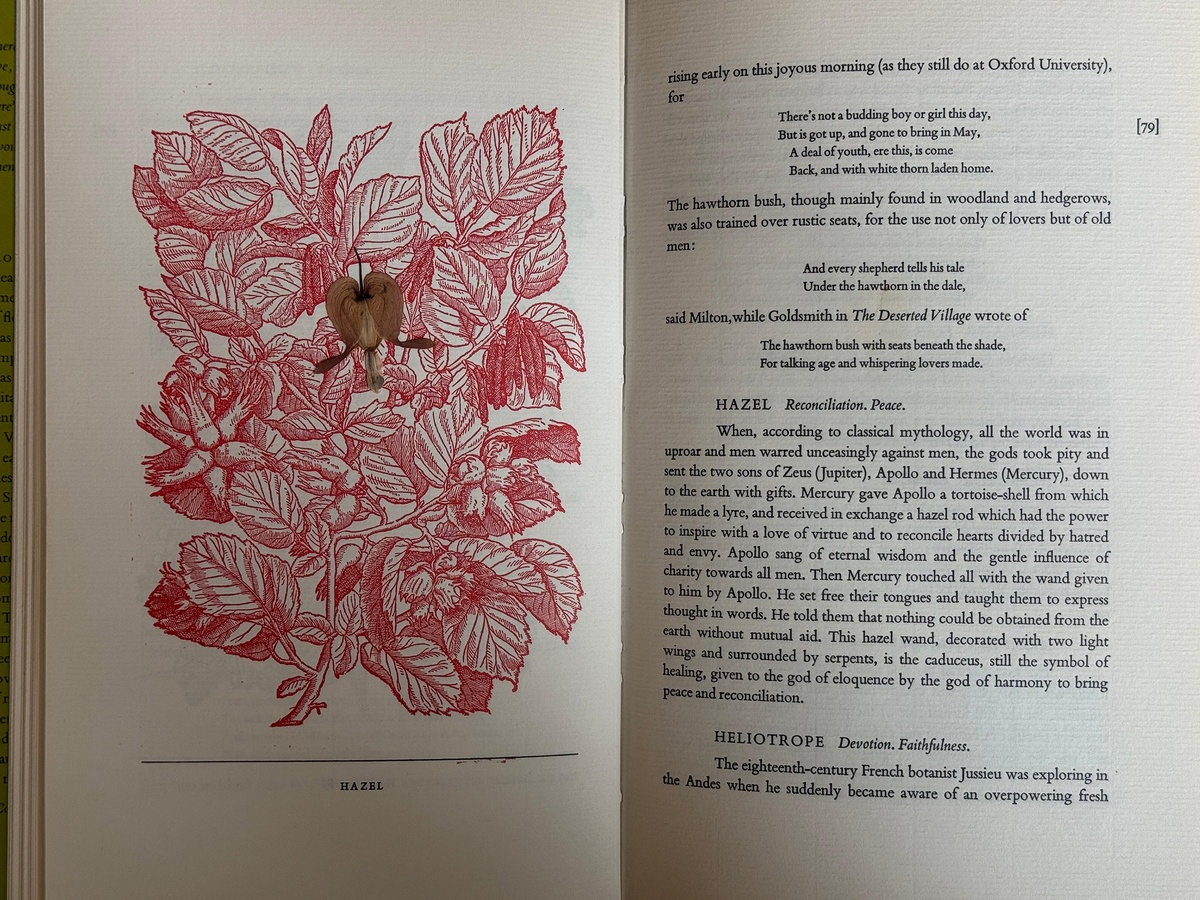

C.F. I adore Viola Odorata, and according to The Meaning of Flowers by Claire Powell, it expresses the sentiment “you occupy my thoughts”. Appropriate, since the original intention of Pear_ed was to spend (more) time with (and also thinking about) plants.

U. Universe

C.F. There was one Pear_ed post where Hayden wrote about Sugar Maple trees and the hypothetical brain of the plant.

L.D. Yes, he was referring to Andrea Celaspino and his theory that a plant’s brain exists in the tips of its new leaves and shoots. Hayden wrote, “year by year the brain hardens and gives itself over to the rest of the universe, before a new(ish) old brain surfaces again.”

C.F. There is a point to the philosophical-sounding description. In cell biology, that’s where the regenerating cells within the new shoot would be located.

V. Vegetables

C.F. I've always found vegetables interesting because they're often not seen as plants. It reminded me of going to Chinese supermarkets with my parents and seeing a variety of ‘unusual’ vegetables. When I was young, these plants didn’t exist outside of home-cooked meals. Over time, I realised that working with plants wasn’t only picking flowers from a field, but having an interest in vegetables also counts.

W. Working difference

H.M. There are a lot of layers to the idea of working. We make things differently because we have individual relationships with plants and ideas. Then, there's also the influence of our professional backgrounds: I work with plants on a day-to-day basis from a landscape architecture perspective, and Cynthia has interacted with plants through her PhD and genetic research. My way of working focuses on the spatial: I think about whether it could block a view, who would clean it up after a year, the colour, and when it would flower.

C.F. Whereas I want to be telling you about the plant DNA, and start from the biochemistry of that. From understanding how the plants’ genes work, I can understand leaf development and then, sculptural potential.

X. Extinction

H.M. It seems like everyone is unaware or ignoring the fact that species are becoming endangered at a rapid rate. Because of that, I want to spend time with the plant species that are with us now and mourn them if they enter extinction. When the politicians on TV tell me that plants aren't dying, I would know it’s not true.

Y. Yucca aloifolia

[from @pear_ed]

H.M. Spanish Dagger (Yucca aloifolia) can be a paintbrush. The skin rots and is scraped off to reveal the ‘threads’. It makes me think of Zander Blom painting with oil using a chopped-up water bottle.

Z. Zhi (靈)

[from @pear_ed]

C.F. [The Chinese mushroom 芝靈] comprises of ling (芝) – spirit, spiritual; soul; miraculous; sacred; divine; mysterious; efficacious; effective – and zhi (靈) – plant of longevity; tungus; seed; branch; mushroom; excrescence. The term zhi, which has no equivalent in Western languages, refers to a variety of supermundane substances often described as plants, fungi, or ‘excrescences’.