Text:

Bhavisha Panchia

Editor:

Sara de Beer

Design:

Ben Johnson

Listening is a practice which brings subjects into relation. It is that preliminary attention which allows for shifts in perception and signification; it is an act through which we construct meaning. Every day we consciously and unconsciously sift through an orchestra of sounds. Whether acoustic or electronic, sounds accompany us in private and public spaces, shape our experiences and movement, and have physical effects on our heart rate, respiration and blood pressure.

Auditory media forms a fundamental part of how we frame our knowledge about the world, and is woven into a mesh of social, cultural and economic power relations. It can be weaponised to create material and symbolic spaces for assembly, for pleasure, and collective experiences. In shops and elevators, the soft sound of muzak is played to lull its visitors into calm. Conversely, music at extremely loud levels is used to torture prisoners in Iraq and Guantanamo Bay. On Wall Street, protestors from the Occupy Movement were pacified and dispersed by police using Long Range Acoustic Devices and sound canons. Closer to home, anti-phonic protest songs and chants in Johannesburg and Cape Town unified protestors as they gathered to demand social justice and economic change during FeesMustFall. Over the past couple of months, Black Lives Matters movements have resounded across the the United States, as protesters and police clashed in Minneapolis and Portland.

The examples above provide critical instances of sound’s material impact on society. But what about the mumbles, whispers and conversations that take place in streets, offices, or in online exchanges? How do we listen to our physical surroundings in the everyday, and the comments and exchanges taking place on online platforms? How do we limit and control what we listen to, and what we hear?

The introduction of the Sony Walkman in 1979 forever changed our relationship to music and public space. It provided, for the first time, an intimacy to sound, presented a soundtrack to daily activities, and aided the drowning out of unpleasant noise. Headphones too, played a significant role in changing how we listen to music within public spaces. Advertisements for Beats Electronics reveal this in their tagline, Hear What You Want1. Forms of auditory self-control – from blocking our ears with our hands and noise abatement headphones, to blocking and unfollowing accounts on social media platforms – help us control whose thoughts, opinions and political viewpoints we allow into our immediate space.

The information we access through the internet is vast, unending, and affords everyone a space to write, speak and create. Yet the ceaseless amount of content and (dis)information being produced and recycled that reaches us gets determined by our personal networks, and global corporations such as Google and Facebook. The late Aaron Schwartz describes this below:

"On the internet, everyone has a channel, everyone has a way of expressing themselves, and so what you see now, is not who has access to the airwaves, but who gets control of the ways you find people…you start to see power centralising sites such as Google, the gatekeepers on the internet who tell you where you want to go, the people who provide you with sources of news and information. So it’s not that only certain people have a licence to speak. Now everyone has a licence to speak…it’s a question of who gets heard."2

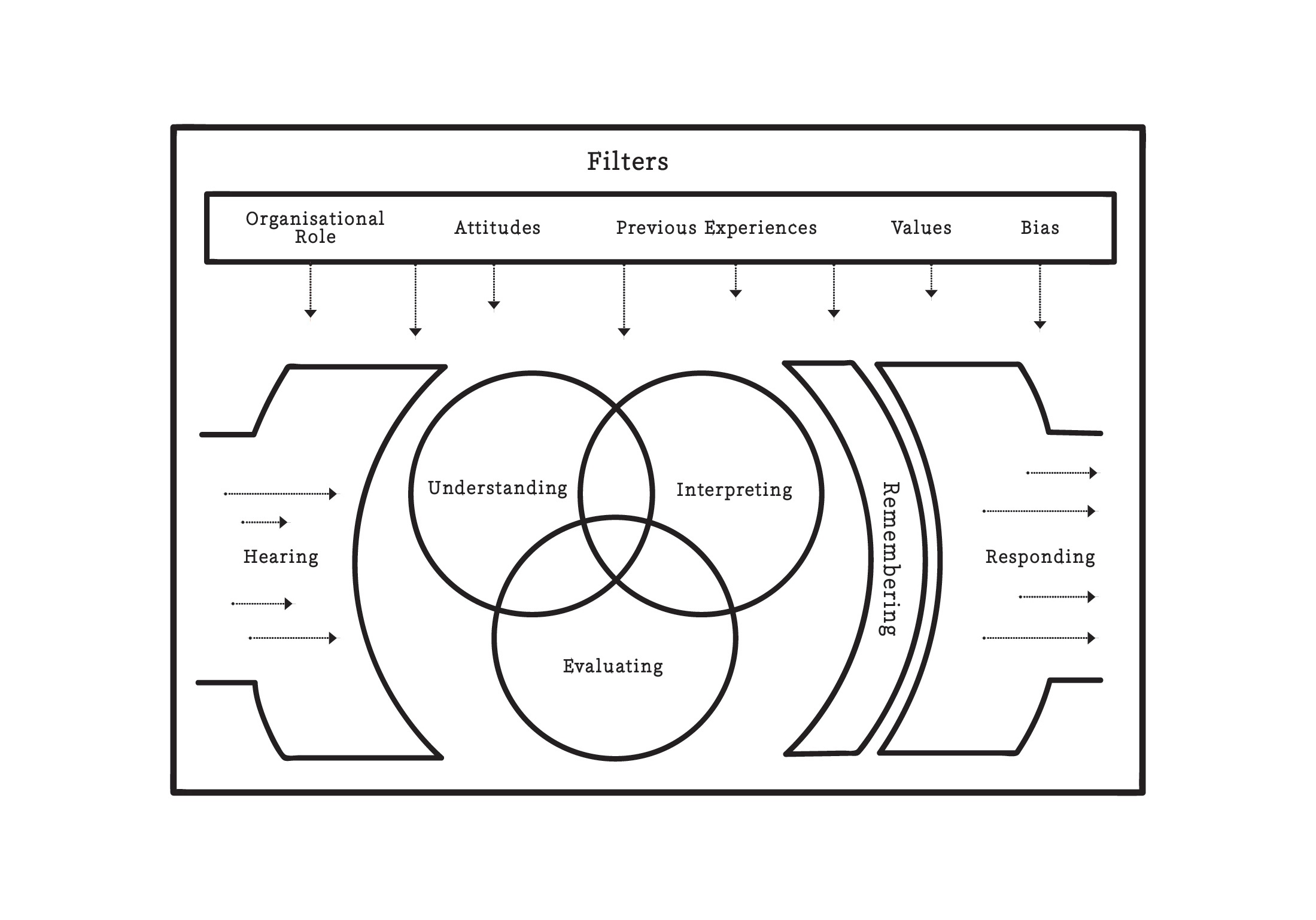

We tune ourselves in and out of conversations, navigating our proximity to attitudes, opinions and ideas. This ‘tuning’ is not just an adjustment of sound within and around our surroundings, but also an adjustment of our own perceptions that are informed by historical, political and economic factors which influence how we listen. Our attitudes, experiences, values and biases are filters that shape our reception to what we listen to, and what we shut out. In short, acts of listening are determined by our personal experiences, and also structure our inter-subjective spaces of exchange.

“To listen to someone requires on the listener’s part, an attention open to the interspace of body and discourse, and which contracts neither at the impression of the voice nor at the expression of discourse.”3

French philosophers Roland Barthes and Jean-Luc Nancy have offered their insights on listening and its connection to human relationships. Both Barthes and Nancy acknowledge listening as an act of decoding. Nancy reminds us that etra a l’ecoutes, ‘to be tuned in,’ was common to the vocabulary of military espionage before it entered public spaces through broadcasting.4 Listening, here, is thought of as an inquiry or investigation, in search of that which remains hidden or obtuse. For Barthes, “[t]o listen is to adopt an attitude of decoding what is obscure, blurred, or mute, in order to make available to consciousness the underside of meaning (what is experienced, postulated, intentionalised as hidden).”5

Of the three forms of listening that Barthes proposes in his text, Listening (the first he describes as ‘alert’, the second as ‘deciphering’), it is the third that I would like to travel with, explained by Barthes as a practice that develops in an intersubjective space and witnesses the interplay of transference: “I am listening’ also means ‘listen to me.”6 The relationship that Barthes outlines above is one of “total interpellation of one subject by another: it places above everything else the quasi-physical contact of these subjects (by voice and ear): it creates transference: “‘listen to me’ means touch me, know that I exist….”7

This relationship resembles what Paul Gilroy describes as “non-dominating social relations”8 and presents a different register of relation across difference. The African-diasporic aesthetic tradition of antiphony – the dialogical musical and social relationship of call and response between two bodies – requires one body to make a demand on another. We must accept and allow the other to make a demand upon us (rendering us passive), and at the same time, we are expected to respond actively to this demand. This antiphonal expression of call and response can only signify insofar as there are receptors to the call; without the response, the call fails to command its subject to attention.

Could the philosophy of Ubuntu, ‘I am because we are’, echo this relation? Is it possible that through listening, we reduce the distance between ourselves and others, in an effort to extend ourselves towards others, through a peer-to-peer relation of non-hierarchic social relations?

In North Africa, Sufi practices court the divine through the performance of music, and offer an example of listening that is an extension of the self. The Sufi practice of sama, meaning ‘listening’ in Arabic, is understood as both a noun and a verb: to listen. Sama is active listening, practiced as a means to alter the state of one’s consciousness, and comprises both the subject (listener) and object (sound) in its very meaning. Singers in this musical genre are not referred to as singers, but instead as listeners. “It is not an ordinary listening, however, but a genre of listening informed by the intention (niya) of listening to find another way of being,” writes Deborah Kapchan.9

Before the days of writing, hearing was taken to be more vital than the sense of sight. Before ‘God’ was represented through portraiture, he was conceived as sound and vibration.10 The schism occurred when different registers of perception were given precedence under epistemological convictions, such as the Enlightenment. Oral and written traditions were placed in opposition to each other. R. Murray Schafer has pointed to the positioning of these practices in relation to Africa and Europe. Having shaped the discursive terrain for the study of the environment with respect to sound and noise, Schafer writes, “In the West, the ear gave way to the eye as the most important gatherer of information about the time of the Renaissance, with the development of the printing press and perspective painting.”11

While sight was given precedence in the West, oral traditions within the African continent remained integral to the cultural livelihood of its society. In the case of the West African griot – a story teller, musician, historian and singer who shares insights with their community through speech and listening – a listening audience is instrumental to their work, for preservation of genealogies, heritage and cultural knowledge. For every speech act, there must be a reciprocating ear.

Cybermohalla Ensemble propose that, “fearless speech requires fearless listening.”12 According to the collective, our thresholds of listening determine what and how much we will hear, and in turn, what speech we will allow around us. Prompted by this proposition artist, curator and writer, Shuddhabrata Sengupta raises the question,

“Can Foucault’s idea of parrhesia, a mode of discourse that a person can use to speak truth to power openly and freely, despite the risks, be complemented by the idea of a mode of fearless listening, and the figure of the ‘fearless listener?’”13

As speaking and listening subjects, Sengupta’s question points to the relationship of transmitter and receiver, the call and the response, the spoken word and the receptive ear – that you can’t have one without having the other.

Bhavisha Panchia is a researcher and curator based in Johannesburg.

This essay was commissioned for the exhibition Sounding the Void, Imaging the Orchestra V.1 curated by Bhavisha Panchia at A4 Arts Foundation, 23 May- 22 August 2019. Featuring works by artists Vivian Caccuri, Chris Chafe, Nick Cave, Andrew Pekler, Robin Rhode, Sahel Sounds, and Jenna Sutela, in addition to a selection of podcasts from Phantom Power and audio media from Nothing to Commit Records, the selected artworks utilised audio phenomena that vary in medium; from vinyl records, video and installation to podcasts, web releases and performance lectures. A public program of talks, workshops and seminars accompanied the exhibition.