Parcours d'atelier

Lemeeze Davids

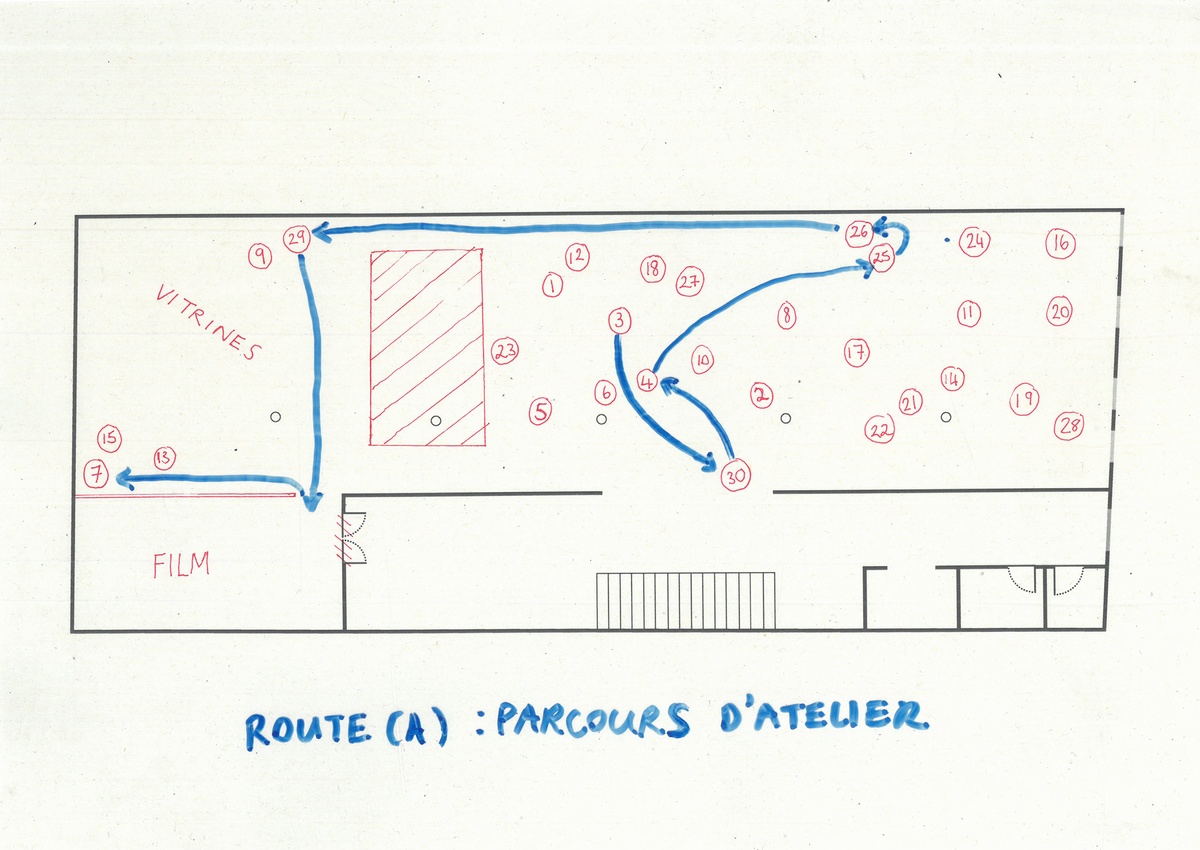

Tracing a studio route through notebooks from William Kentridge’s History on One Leg (2024) at A4. – March 5, 2025

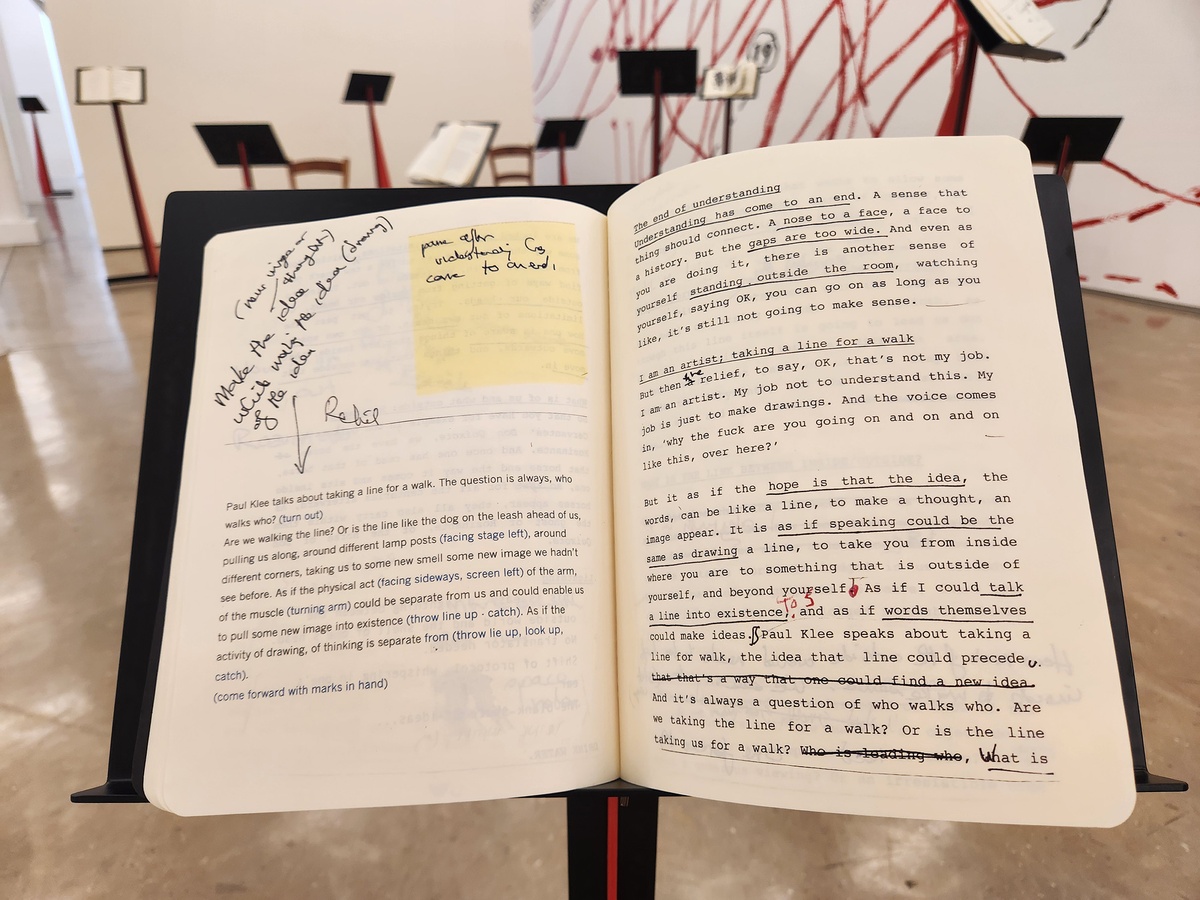

In a famous aphorism in his 1915 Pedagogical Sketchbook, German-Swiss artist Paul Klee notes that ‘a line is a dot that went for a walk’ – pointing out how a line has the ability to conduct movement across a space.These dynamic lines are central to William Kentridge’s History on One Leg (2024) at A4, where we can trace a parcours d’atelier (or studio route) through a choreography of past notebooks of the artist.

Our beginning point is a few pages back from the centre spread in Notebook 3: Kentridge unpacks the Paul Klee quote, thinking about taking a walk through the studio as an exercise in drawing.The Klee excerpt was included in Kentridge’s preparation for a lecture around Nikolai Gogol’s satirical short story The Nose (c.1837), which can be seen on the right hand page.

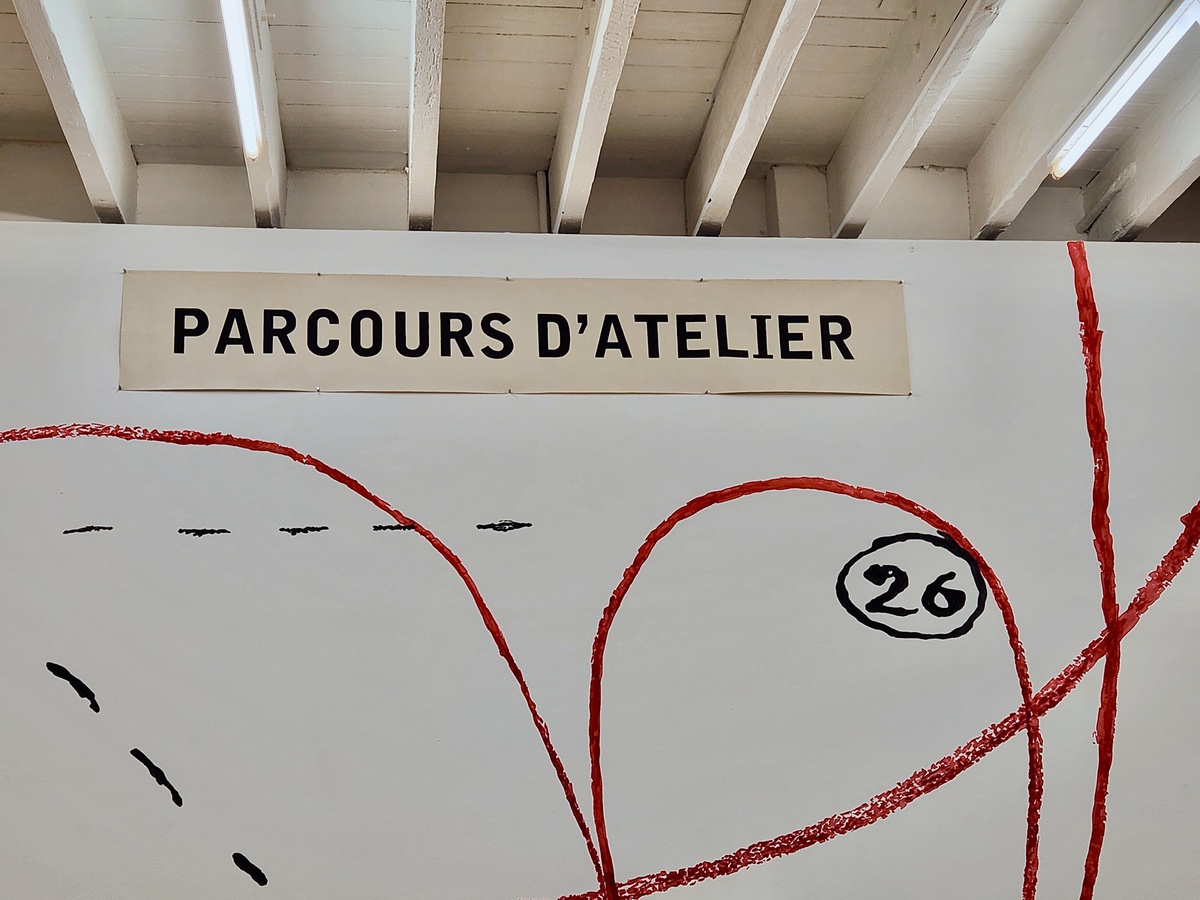

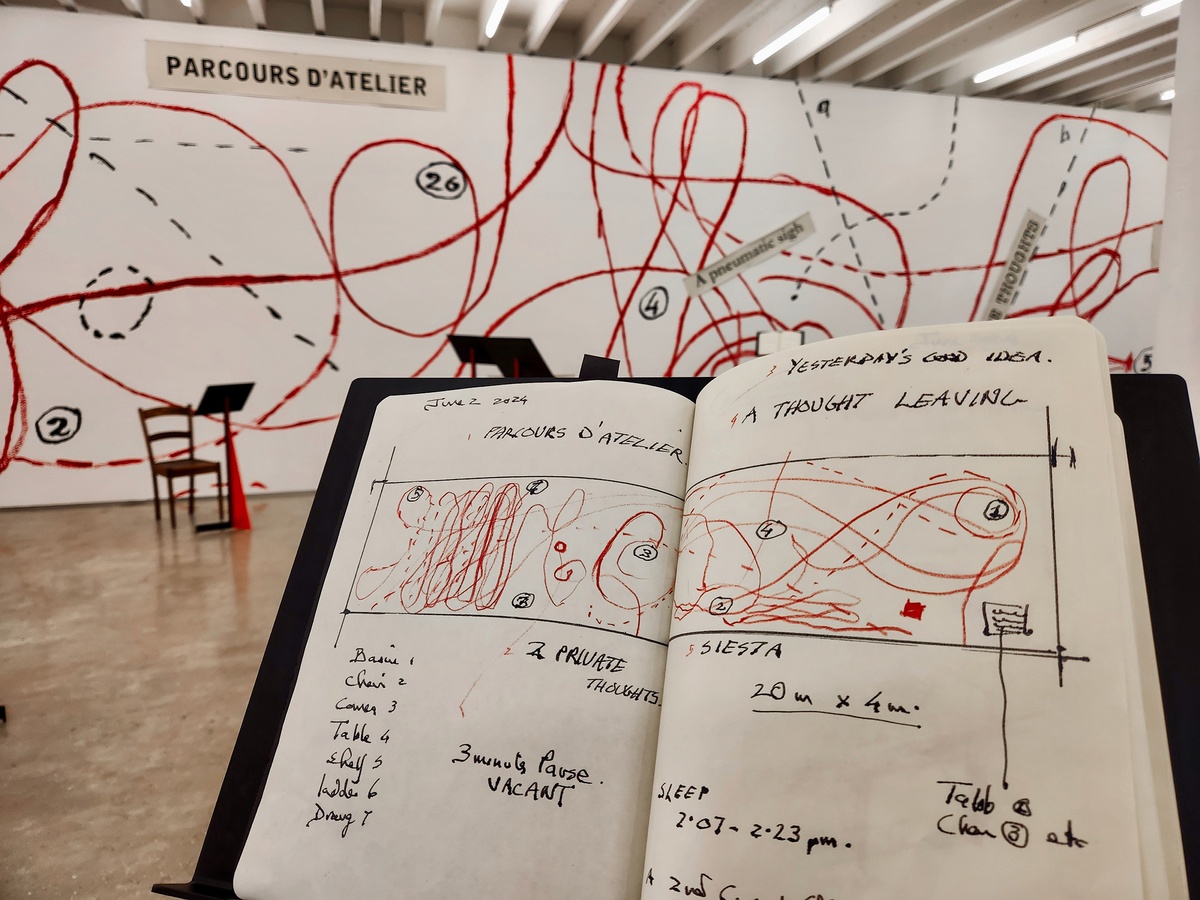

The notebooks are arranged to make way for a meandering, introspective path through the studio. Kentridge paces up and down as he thinks, before he draws.The phrase Parcours d’Atelier appears both in the Gallery on hand-painted canvas tacked above the wall mural and in Notebook 30, which houses the planning notes for History on One Leg. Let’s compare them side by side.

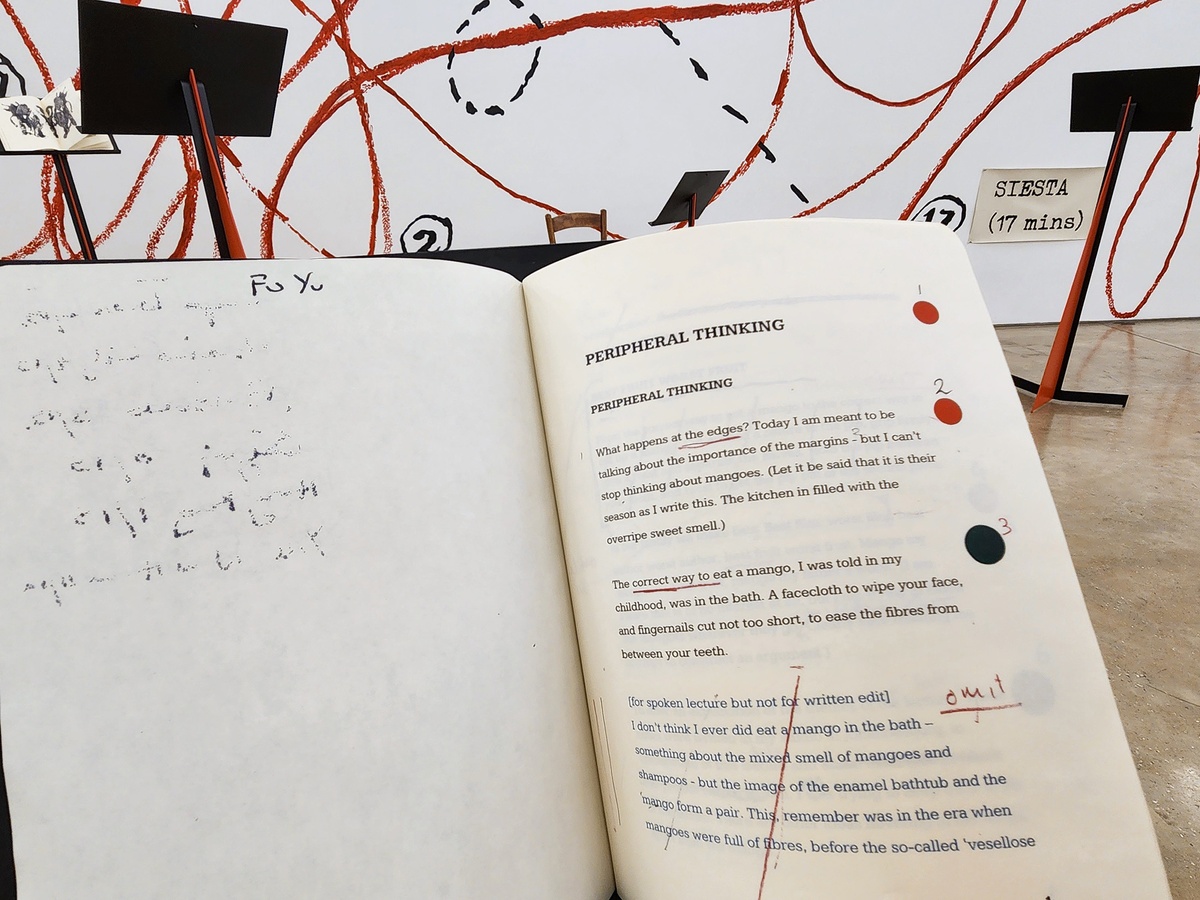

From 30, I find it most useful to read Notebook 4, which is close-by to the left.This is a lecture on peripheral thinking: the ideas that pull us out of focus and into the margins of our mind. Kentridge writes, “Today I am meant to be talking about the importance of the margins – but I can't stop thinking about mangoes. (Let it be said that it is their season as I write this. The kitchen [is] filled with the overripe sweet smell.)”

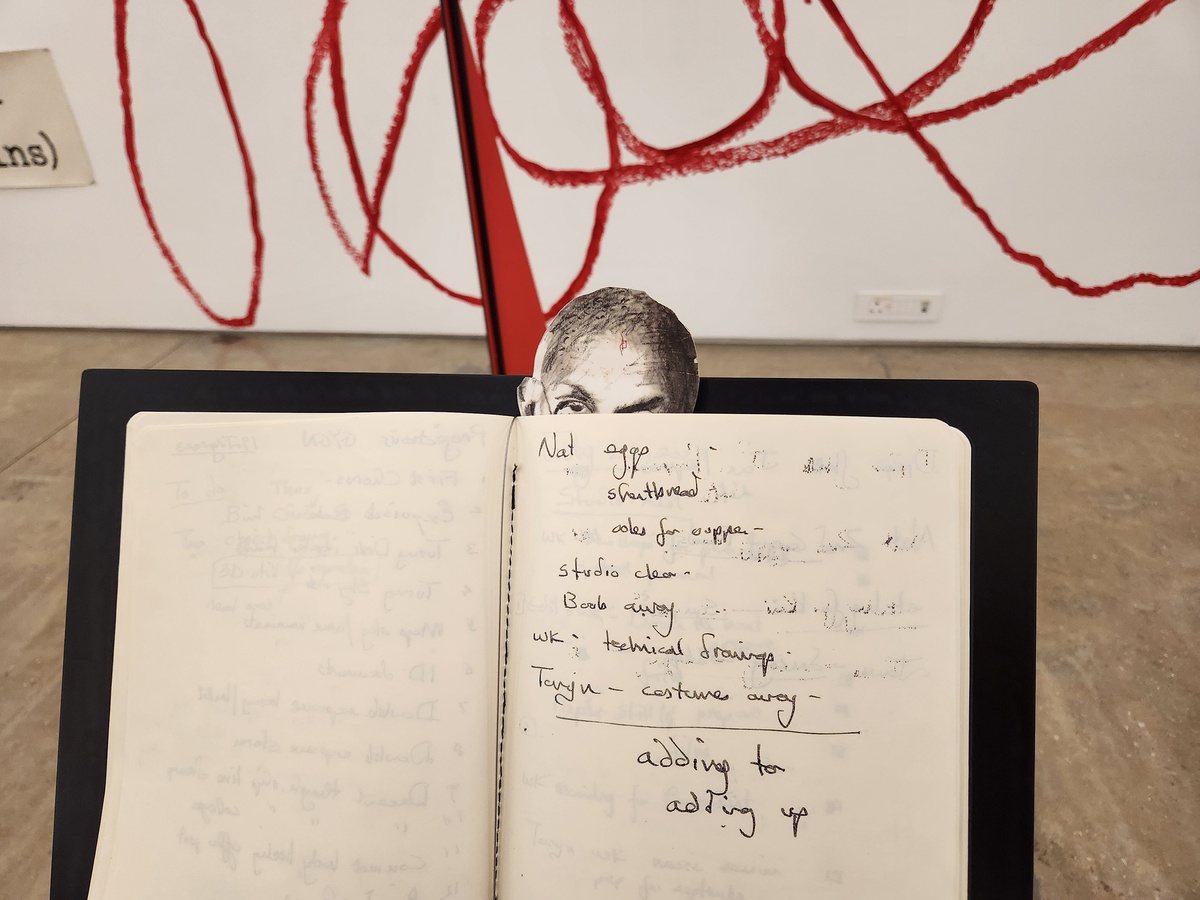

Any notebook often contains these mental wanderings. The smell of mangoes interrupting productivity. A doodle in the corner. A list of groceries on the side. Shorthand that only the writer can decipher.Across the installation, we might see something that transcends the margins even further – an eye peeking out at us from inside Notebook 25.

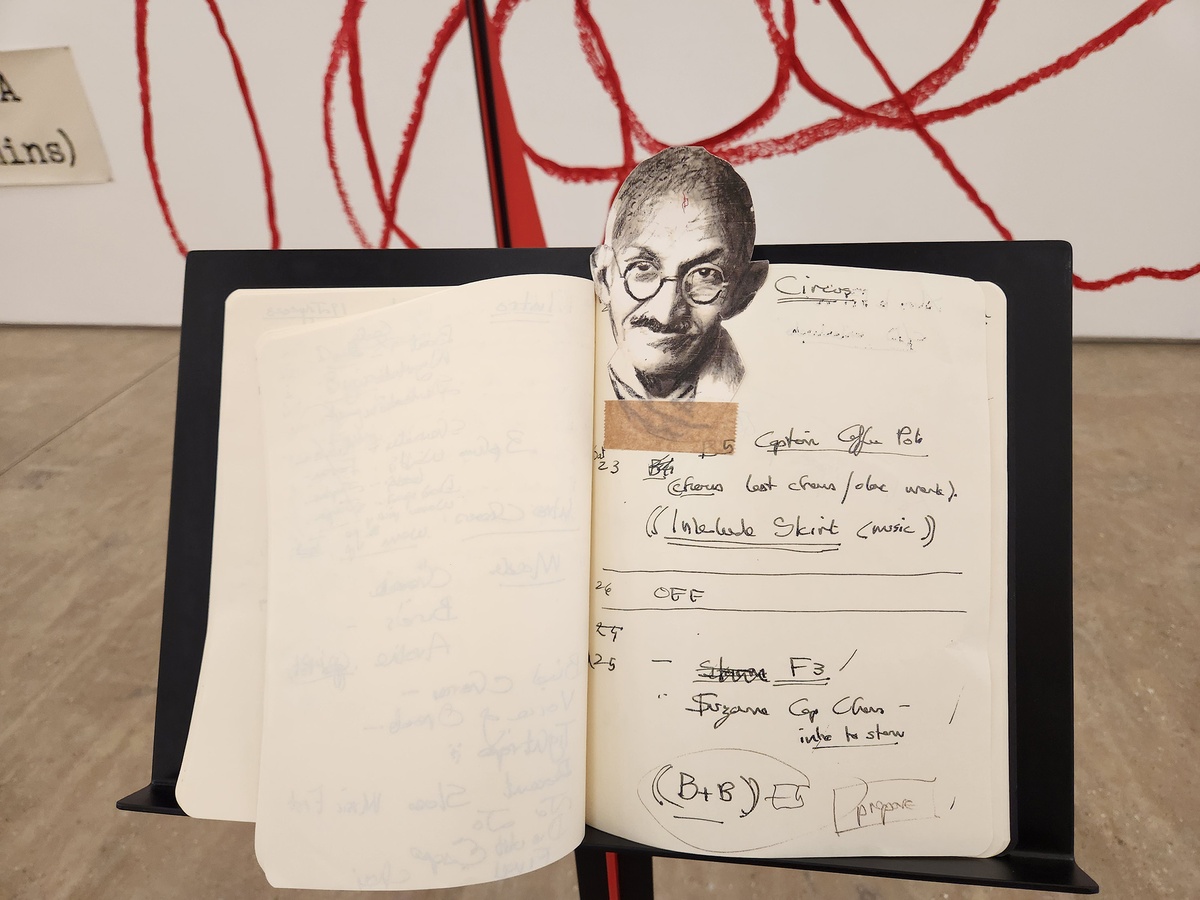

Notebook 25 carries the preparatory notes for The Great Yes, The Great No (2023) – part play, part Greek choir, part chamber opera. The production narrates an escape on a boat from France to Martinique. The passengers include notable figures like André Breton, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Wilfredo Lam, Victor Serge, and Anna Seghers, amongst others.Mahatma Gandhi appears amongst the planning ephemera, extending past the edges of the notebook. He is not mentioned as one of the passengers, but perhaps he was considered to be included at one point.

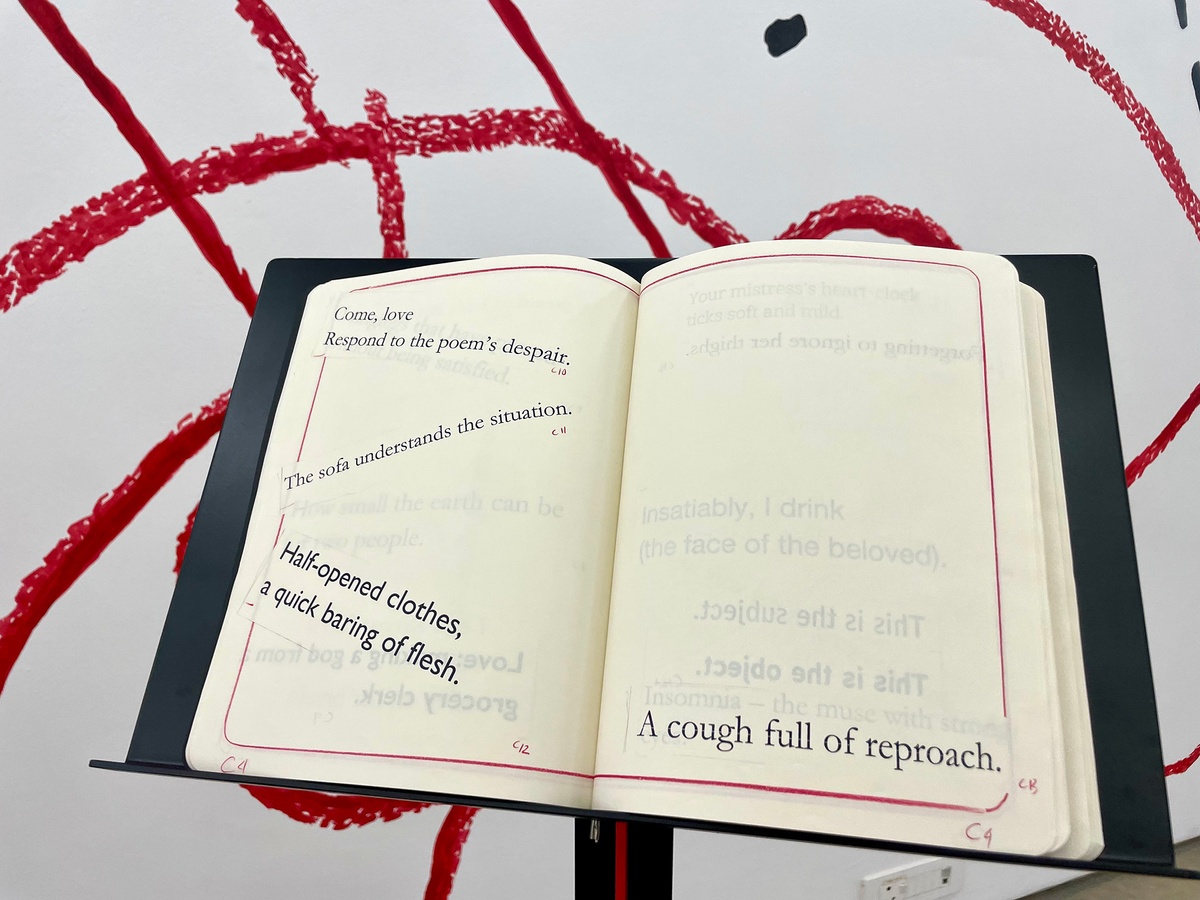

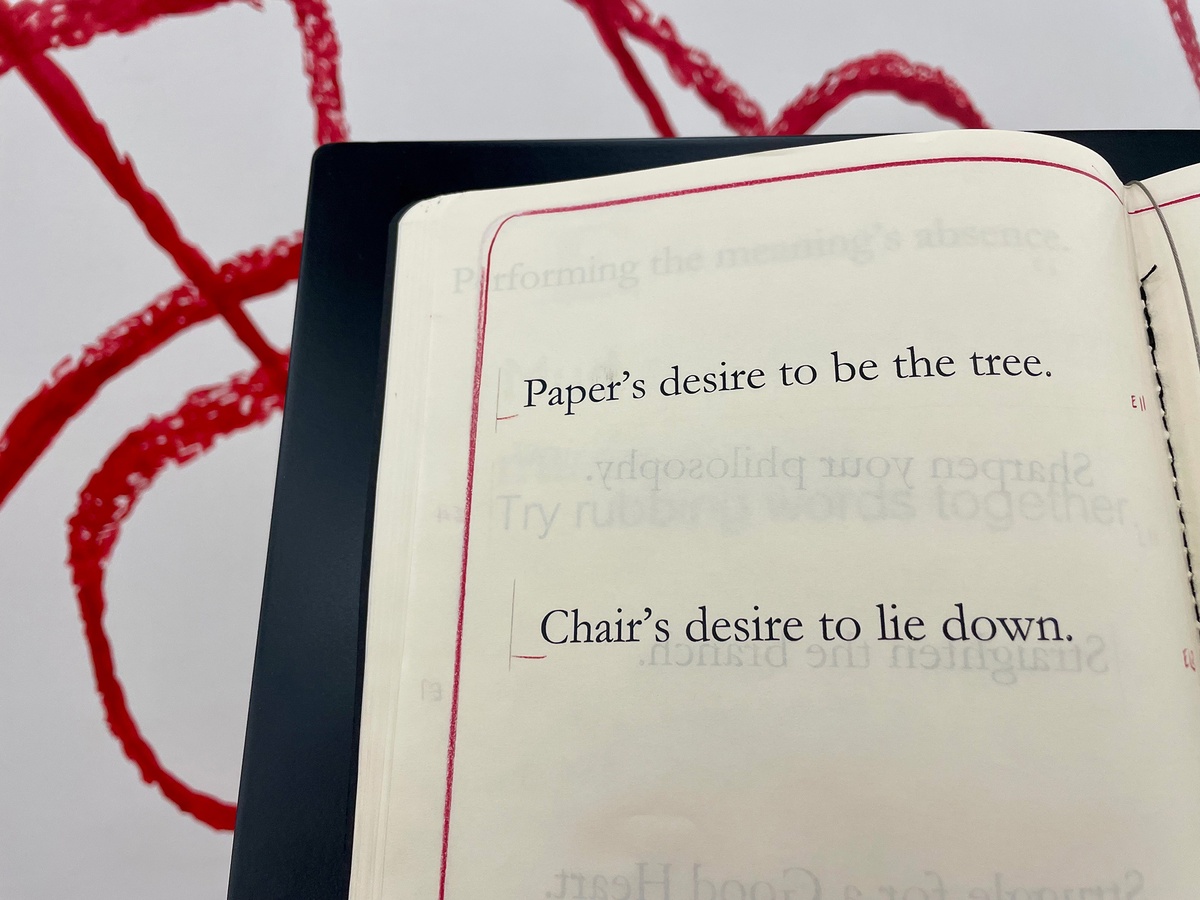

Right next to 25 is Kentridge’s WORDS, a collation (2023) as Notebook 26, one of the few that has been published as a book. The publication contains a collection of phrases from various sources that have resonated with the artist, sitting alongside a few sketches in red pencil.Like the other phrases displayed on the walls around the installation, these snippets of text are often the beginnings of larger projects.

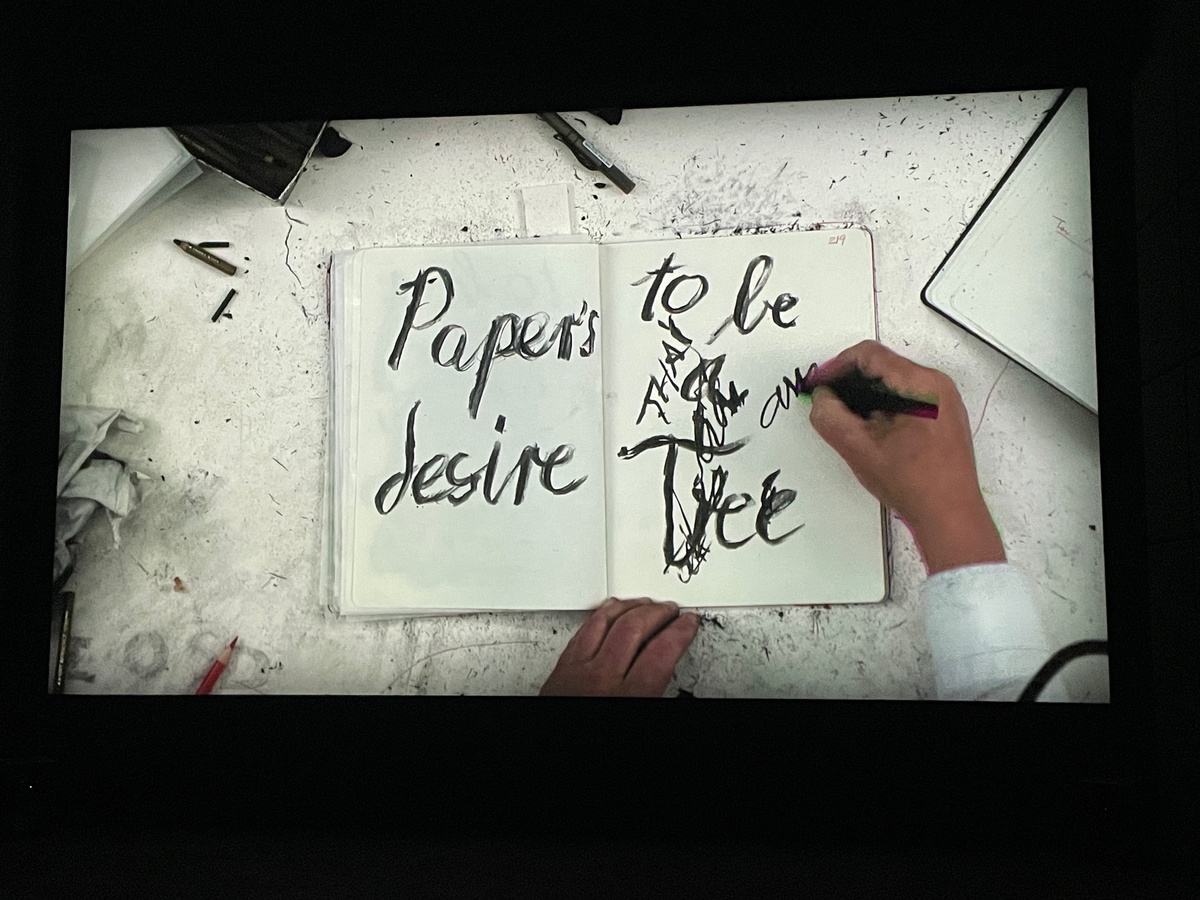

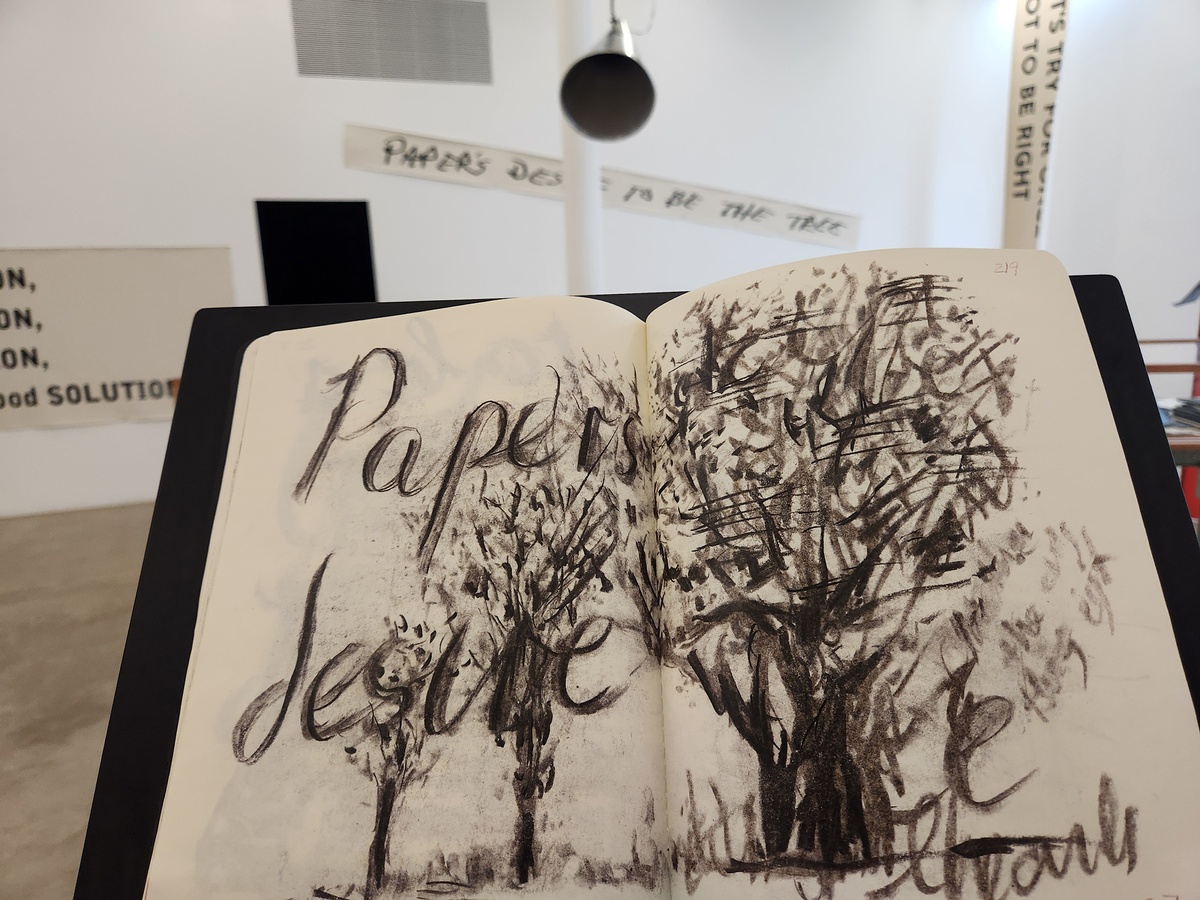

“Paper’s desire to be the tree,” types Kentridge, in Notebook 26. Including this appearance, the phrase appears four times in History on One Leg.The second time is in Notebook 29, a copy of the sketchbook that the artist uses to create and animate Fugitive Words. The film plays in the media room across from the book, and gives us the third instance of the phrase.

The last sighting is on a hand-painted wall phrase, placed on the wall just outside the media room and also across from Notebook 29, which is visible in one’s peripheral vision.

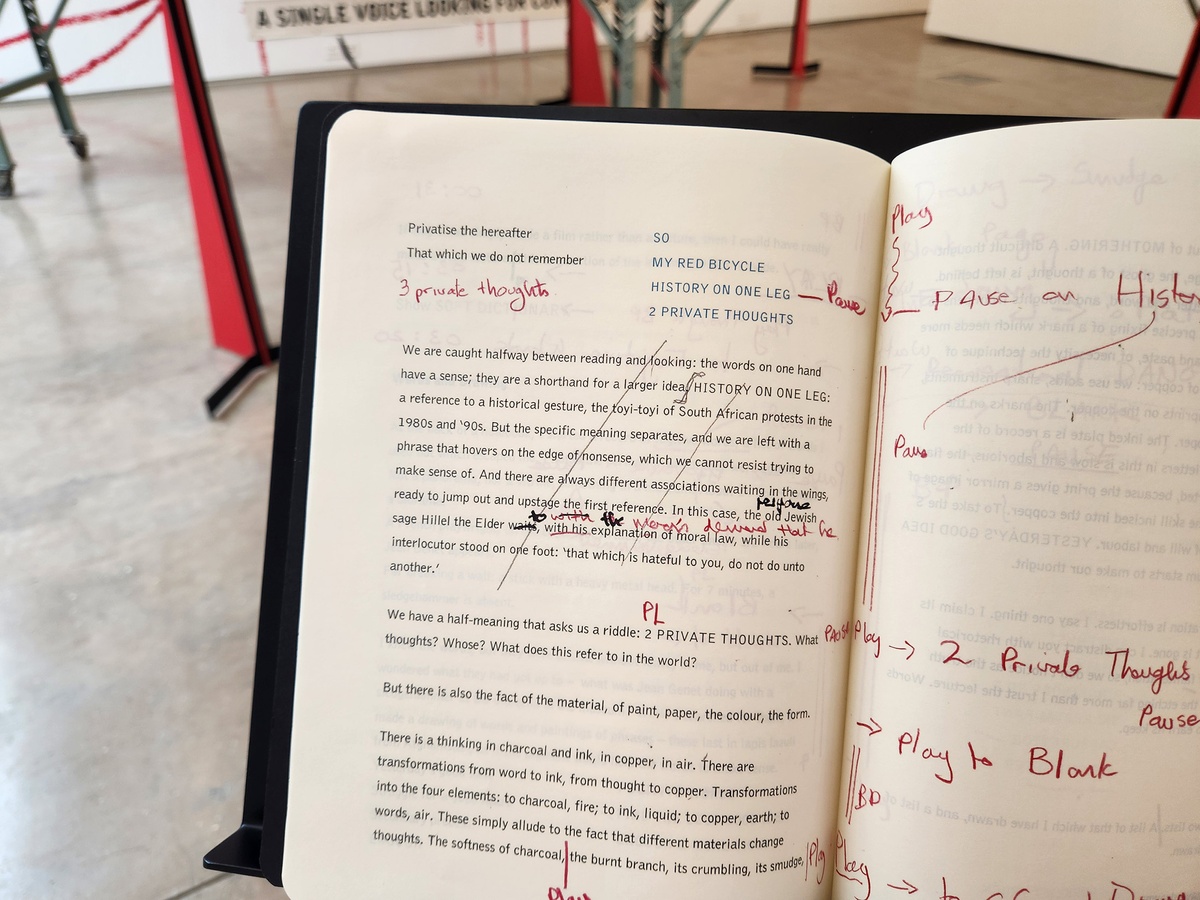

Positioned under this canvas, my last stop is where Kentridge speaks about the title of the exhibition, History on One Leg.What does it allude to? He explains that “we are left with a phrase that hovers on the edge of nonsense, which we cannot resist trying to make sense of.” The notebook text features technical instructions for the performance lecture, in which he signals to “Pause on History on One Leg”.

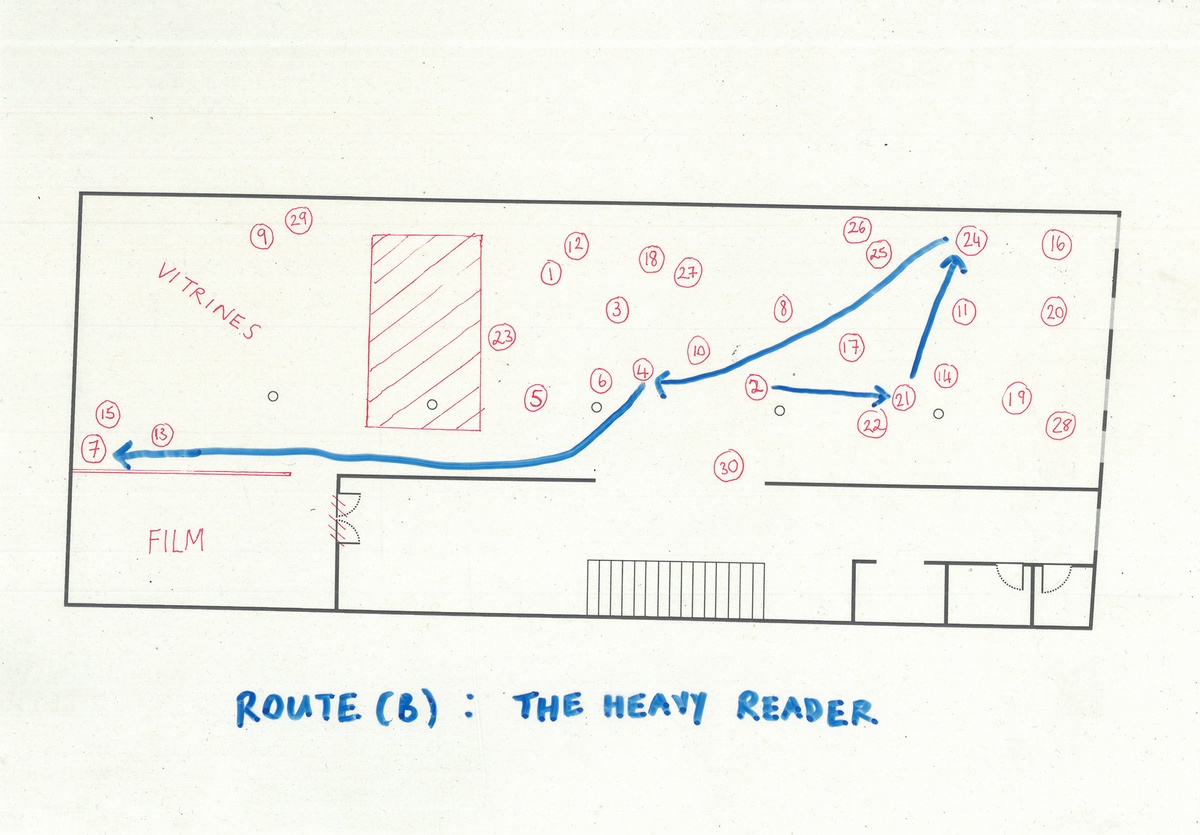

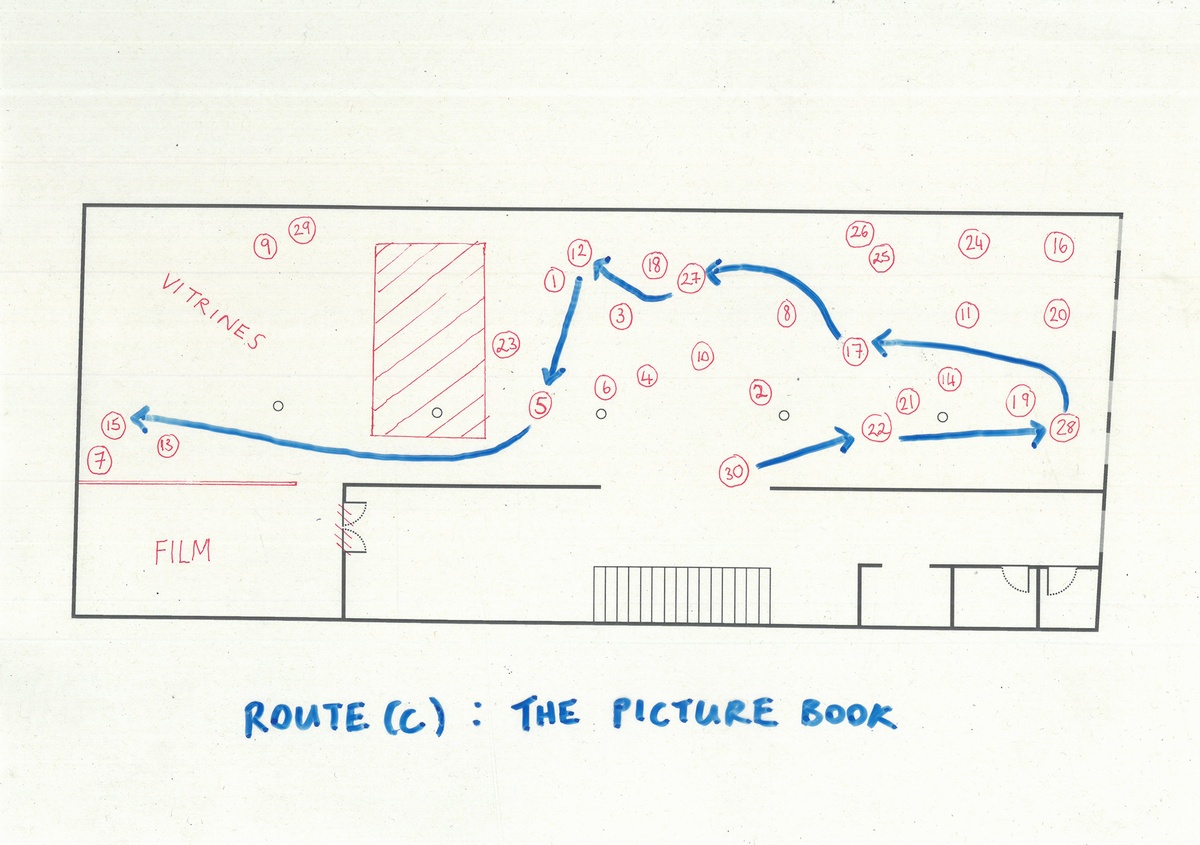

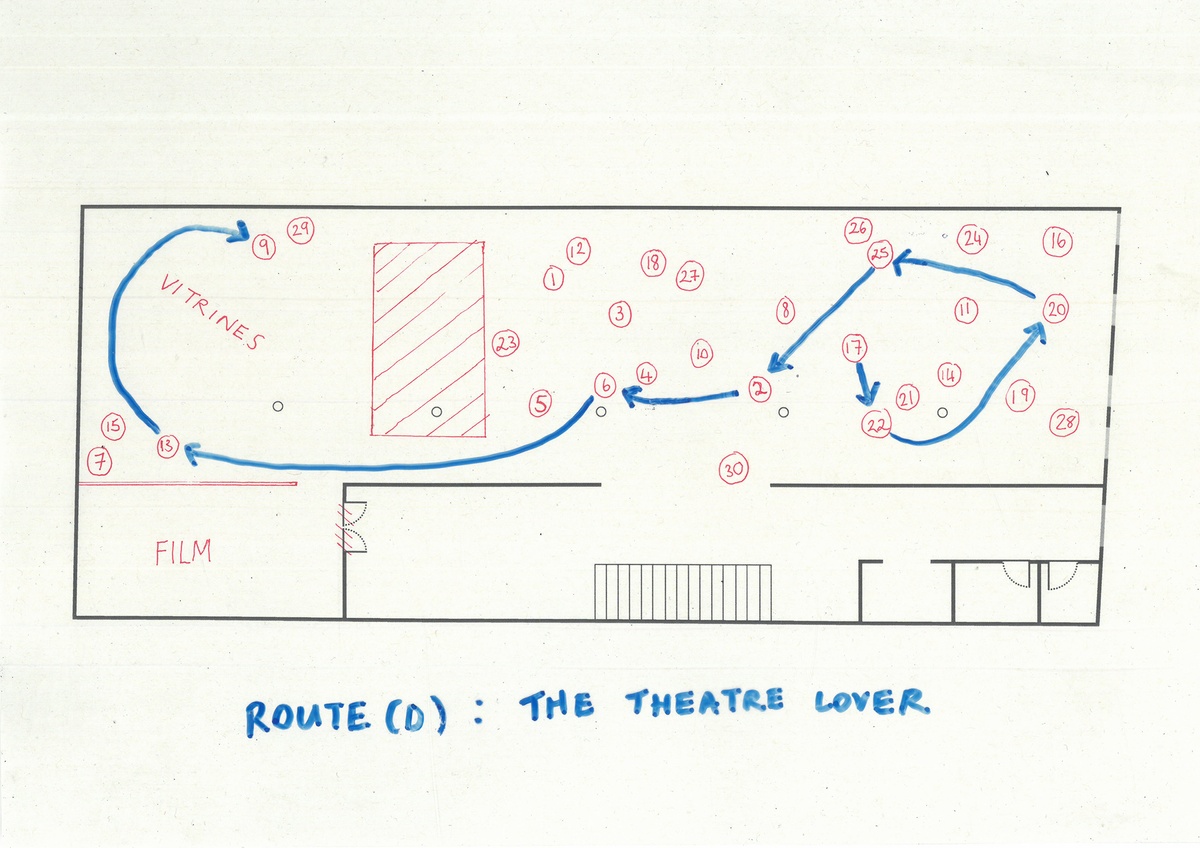

History on One Leg contains 30 notebooks that give generous insight into Kentridge’s practice over the last 15 years.Let me include a few more routes one might undertake.

The ‘Heavy Reader’ route is a walk through the longer texts in the notebooks. It includes lectures on History vs. The Studio, peripheral thinking, and some of the listed sources of Kentridge’s ‘words’.

The ‘Picture Book’ route is for those who want to see more sketches, images and visualisations instead of reading. The trail covers sketches for sculptures and productions, pasted-in inserts of Johannesburg Art Gallery, news clippings, and self-portraits.

Lastly, we have the ‘Theatre Lover’ route, which guides the visitor through Kentridge’s stage-related notebooks – operas, dialogue, film logistics. The productions include The Great Yes, The Great No, The Nose, The Fasting Showman, and Myakovsky: A Tragedy.

On my own walk through the notebooks, I have found that these small trails have made sense to me, but more gems lurk in the pages in between the studio to-do lists and literature annotations. One only has to venture on a parcours d’atelier to find them.